|

|

|

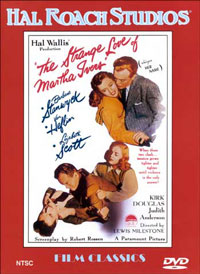

Fate drew them together ... and only murder could part them! The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (Die seltsame Liebe der Martha Ivers) USA 1946 by Lewis Milestone with: Barbara Stanwyck (Martha Ivers), Van Heflin (Sam Masterson), Lizabeth Scott (Toni Marachek), Kirk Douglas (Walter O’Neil), Judith Anderson (Mrs. Ivers), Roman Bohnen (Mr. O’Neil), Darryl Hickman (Sam Masterson, as a boy), Janis Wilson (Martha Ivers, as a girl), Ann Doran (Secretary), Frank Orth (Hotel Clerk), James Flavin (Detective # 1), Mickey Kuhn (Walter O’Neil as a boy), Charles D. Brown (Special Investigator) |

|

Tom Milne, Time Out This masterful psychological thriller could not have been more persuasively directed. The screenplay — tight, tough, and cynical — was Robert Rossen's last assignment before he turned to directing his own scripts. Manny Farber, writing in the New Republic in 1946, began his review: »The latest Hollywood film to show modern life as a jungle... a jolting, sour, engrossing work. It deals with four people who have lived cataclysmic, laughterless lives since they were babies. Pacific Film Archive

Jean-Pierre Coursodon, Bertrand Tavernier: Spécimen particulièrement original de film noir prouvant la richesse et la malléabilité du genre. Ici le film noir offre au développement du destin des personnages un véritable espace romanesque où s'élabore un passionnant suspense psychologique et moral. Grâce à la maturité du scénario de Rossen et à la minutie du travail, de Milestone, l'évolution sinueuse, hésitante et subtile des personnages, leurs chances respectives de salut qui tantôt paraissent infimes, tantôt grossissent d'un nouvel espoir, alimentent la matière d'un drame dont les éléments sont plusieurs fois remis en question tout au long de l'intrigue. De nombreux thèmes propres au genre (la femme fatale, la domination du passé sur le présent) s'enrichissent ici de variations inattendues. Deux des personnages resteront engloutis dans le passé et la tragédie ; deux autres réussiront à sortir, sinon indemnes, du moins plus lucides et plus aguerris, de l'enfer bourgeois et provincial d'Iverstown, savamment décrit par Rossen et Milestone. Prodigieuse interprétation des quatre protagonistes principaux et tout spécialement de Van Heflin et de Lizabeth Scott, formant l'un des couples les plus crédibles et les plus attachants du cinéma américain de l'époque. Premier film de Kirk Douglas. Jacques Lourcelles: Dictionnaire du cinéma, vol. 3: Les films

The final double suicide L'emprise du crime de Lewis Milestone, mérite une attention particulière. C'est peut-être le chef-d'œuvre d'une carrière qui compte plusieurs réalisations très valables, trop souvent oubliées au profit du seul A l'ouest rien de nouveau (1930). Proche de la psychologie criminelle pure, cette étude de mœurs provinciales, complexe et corrosive, s'organise autour d'un couple incontestablement 'noir', l’attorney O'Neill et sa femrne. Dernier rejeton d'une dynastie d'industriels respectés, Walter, veule, alique et jaloux, a épousé, par amour et par esprit de farnille, une Martha qui le déteste, mais lui reste liée par un grave secret (leur faux témoignage a fait jadis condamner un innocent). Elle a eu une jeunesse agitée d'orpheline fugueuse, en conflit avec une tante qui mourra dans des conditions dramatiques. Son sang-froid perfide ne l'empéche pas d'être encore attirée aujourd'hui par Sam, un ami d'enfance, dont l'existence vagabonde a toujours représenté pour elle l'idéal d'une vie sans loi. Un jour, elle lui suggére vainement d'assassiner son mari, tombé ivre-mort au bas de l'escalier. Walter, de son côté, tâche de faire tuer ce rival par ses inspecteurs. Mais Sam décoit toutes ces espérances et vient cracher son mépris à la face du couple, qui se suicide devant cette situation sans issue. Raymond Borde/Étienne Chaumeton:

[…] In the postwar period, Hal Wallis’s predilection for producing extremely romantic novels and stories often placed his films in a category of their own. His major characters suffered from psychological obsessions and neuroses but were infrequently criminals from the lower classes, whose presence can give film noir a lurid appeal. Alain Silver/Elizabeth Ward:

|

Director: Lewis Milestone Runtime: 117 min Awards: Academy Awards 1946 Nominated Oscar Best Original Screenplay Jack Patrick // Cannes Film Festival 1947 Competing Film |

|

THE STRANGE LOVE OF MARTHA IVERS arrives on DVD through the auspices Hal Roach Studios and Image Entertainment. This 1946 production predates wide screen, and the full screen black and white transfer is a very good representation of its theatrical framing. As I stated above THE STRANGE LOVE OF MARTHA IVERS was on the verge of nitrate decomposition, so the presentation does have a number of flaws, due to the shape of the film elements. For the most part, THE STRANGE LOVE OF MARTHA IVERS looks quite good, with the majority of the film coming from first generation 35mm elements. There are some shots within the body of film that seemed to have been replaced with either very good 16mm inserts or 35mm materials that are several generations off the original negative. The transfer provides a modestly good level of sharpness and detail. Film grain is noticeable in a numbers of places, as are early signs of nitrate decomposition. However, other signs of age, like scratches and blemishes are relatively minor. Blacks are very accurate on most of the film, but there are places where they lean towards gray. Contrast is decent, although the whites appear somewhat blown out at various points throughout the film. Digital compression artifacts are not a problem on this DVD. thecinemalaser |

Image Entertainment / Hal Roach Studios |