|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

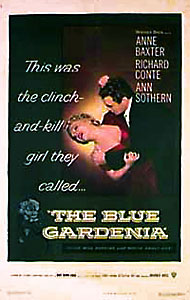

The Blue Gardenia

(Gardenia — Eine Frau will vergessen | La Femme au gardénia)

|

|

|

| |

|

USA 1953 | 90 min

Director: Fritz Lang

Producer: Alex Gottlieb

Production Company: Blue Gardenia Productions / Gloria Films for Warner Bros.

Screenplay: Charles Hoffman (based on the short story Gardenia by Vera Caspary)

Cinematographer: Nicholas Musuraca, A.S.C. (b/w, 1.37:1 Academy Ratio 35mm)

Editor: Edward Mann

Music Score: Raoul Kraushaar

Song: Lester Lee, Bob Russell

Sound: Ben Winkler (Mono)

Art Director: Daniel Hall

Costume Design: Maria P. Donovan

Cast: Anne Baxter (Norah Larkin), Richard Conte (Casey Mayo), Ann Sothern (Crystal Carpenter), Raymond Burr (Harry Prebble), Jeff Donnell (Sally Ellis), George Reeves (Haynes), Nat "King" Cole (Nat "King" Cole)

Shooting: 28 November – 24 December 1952

Premiere: 28 March 1953 (USA) | 20 November 1953 (BRD)

|

|

|

International Movie Database International Movie Database |

All-Movie Guide All-Movie Guide |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Ein geräumiges Ein-Zimmer-Appartment, bewohnt von drei jungen Frauen, Angestellten, eine verlobt, eine geschieden, eine mehr als an Männern an Comics interessiert. Die Kamera folgt ihren Bewegungen, vergleicht, stellt Beziehungen her — Lang entwickelte dafür den crab dolly, einen mobilen, kleinen Kamerawagen, der es ihm erlaubte, frei und prazis im Raum zu fahren und zu schwenken. Das gibt dem Film einen leichten Start.

Ihre Extrovertiertheit und Disponibilität macht die Mädchen verletzlich. Die Verlobte, Anne Baxter, will den Abend ihres Geburtstages allein mit dem Bild ihres in Korea stationierten Bräutigams feiern, sie öffnet seinen letzten Brief, erfährt, daß er eine andere heiraten wird. Darauf nimmt sie die eigentlich nicht ihr, sondern einer ihrer Zimmergenossinnen zugedachte Einladung eines Zeichners an, läßt sich von dem Schürzenjäger betrunken machen, muß sich seiner Zudringlichkeit erwehren schlägt ihn — an mehr erinnert sie sich nicht. Dann ist er tot, und sie hält sich für schuldig.

Der dritte Mann in ihrer Geschichte, nach dem Verlobten und dem Zeichner, ist ein Reporter, der durch einen »Offenen Brief« versucht, Kontakt zu der Frau zu bekommen, die den Zeichner getötet hat. Wieder läßt die Offenheit der jungen Frau, ihre Kontaktbereitschaft sie in die Falle gehen, die ein Mann ihr stellt. Als sie sich vertrauensvoll mit dem Reporter treffen will, wird sie verhaftet.

Auf den Artikel des Reporters hin haben verschiedene Frauen angerufen. Daß man sie dabei nicht nur hört, sondern sieht, in präzis gezeichneten Räumen und Situationen, bewirkt eine jähe Offnung des Film-Raums, das Aufreißen vieler Türen in eine Flucht von anderen Räumen. Der Fächer, auf dem man erst die drei Freundinnen sah, entfaltet sich weiter, zeigt Selbstbewußte und Hysterische, die unterschiedlich reagieren auf die doppelte männliche Provokation: die des Schürzenjägers und die des Reporters, ob sie dem einen sein Schicksal gönnen oder der professionellen Indiskretion des anderen sich widersetzen.

Noch eine junge Frau kommt ins Spiel, die »wahre Schuldige«. Ihre Entdeckung und die Entlastung der zu unrecht Verdächtigten bedeutet aber keinen Eclat. Anne Baxter grüßt die »Mörderin« schwesterlich, sie könnte auch die andere sein, wie sie anstelle einer anderen zu dem Rendezvous ging. We are sisters under the mink, wir sind Schwestern unterm Nerz, sagt die Gangsterbraut zur Polizistenwitwe in Langs nächstem Film.

Enno Patalas/Frieda Grafe: Fritz Lang

München-Wien 1976, S. 128-130

Fritz Lang is one of the few major directors whose name is repeatedly associated with the noir cycle in the 1950s through such films as Clash By Night, The Blue Gardenia, The Big Heat, and Human Desire. Tied to a narrative that was rather unimaginative, The Blue Gardenia was the weakest of the four; yet Lang, together with a capable cast and photographer, was able to imbue it with his sense of the maudit. A newspaper-oriented melodrama, which makes connection with a host of neurotic personalities, is an appropriate vehicle in the 1950s for a study of middle-class alienation. An indication of the changing aspect of the noir cycle is that The Blue Gardenia as directed by Lang and as photographed by Nicholas Musuraca was largely composed of flat, neutral gray images most representative of 1950s television with its overhead lighting. The diminished influence of a particular studio or visual style is evidenced by Musuraca, whose presence helped define the noir style at RKO but who contributes only a few expressionistic moments in The Blue Gardenia: an occasional rain-streaked window or Prebble's murder reflected in the glass of a broken mirror. Despite this high-key visual style, Lang does exploit to advantage certain technical developments in motion pictures. The location work complements the images in giving the film a surface value in a realistic rather than expressionistic tradition. Lang also uses the mobility of the crab dolly to follow his characters with a nervous insistence that anticipates the hand-held camera. The circling motions around the unfortunate Norah become vectors in a relentless determinism that is most typical of Lang's noir vision.

Alain Silver, Elizabeth Ward:

Film Noir. An Encylopedic Reference to the American Style

New York 1992, p. 38

The Blue Gardenia gives us an archetypal noir situation: a murder takes place and the heroine believes that she may have committed the murder. However, because she was drunk when the murder took place, she isn't sure what happened. Film noir would mine this territory well as it examined the dark forces within ourselves and our inability to control those forces (as in Double Indemnity and Fear in the Night). Just three years before The Blue Gardenia was released, Nicholas Ray directed his own essay on this topic—In a Lonely Place. While The Blue Gardenia uses the murder as a gimmick, with no intention of exploring the psychological ramifications for more than a few thrills before restoring normality, In a Lonely Place takes us to the edge of the abyss, giving us a lead character who may or may not be responsible for a series of murders, and then it strands us there.

Director Fritz Lang himself characterized The Blue Gardenia as "venomous," but venom is exactly what this movie lacks. Anne Baxter as the heroine is too virtuous to ever really risk our faith. She commits a slight indiscretion by going out drinking with a stranger (Raymond Burr) after her soldier boyfriend dumps her. But there are no murderous tendencies hidden within her psyche. The storytelling solely blames liquor for the err of her ways. And therefore, regardless of the police dragnets, the movie lacks tension. We know she'll be exonerated (unlike Humphrey Bogart's alcoholic war veteran in In a Lonely Place, who may actually be capable of murder). But even if the movie treats its main character with kid gloves, The Blue Gardenia is still a fun movie. Raymond Burr gives one of his best performances as an artist/playboy who routinely takes advantage of every woman that makes herself available to him. Nicholas Musuraca provides the cinematography, including an especially striking image of a mirror shattering as Baxter raises a fireplace poker to strike Burr. And Nat "King" Cole is on hand as a nightclub singer who performs the movie's theme song.

Fritz Lang's stint in Hollywood had lasted nearly twenty years by the time he directed Blue Gardenia. (He came to America in 1934 with a contract from David O. Selznick and MGM; this contract resulted in only one film, Fury [1936].) The production circumstances surrounding this film, his seventeenth Hollywood feature, were all too typical of his experiences within the American film industry in general: minuscule budget (and minimal salary), very little involvement in pre-production decisions, for example, script development, choice of actors, and working under a highly abbreviated production schedule. Blue Gardenia, in fact, was even more bargain basement than Lang was used to, an emblem of Lang's decreasing prestige. Alex Gottlieb, the independent producer of Blue Gardenia, is best known for having produced the first ten Abbott and Costello films for Universal at budgets and production schedules on a par with Blue Gardenia. (Later, Gottlieb would become the producer of such television shows as 'The Donna Reed Show,' and 'The Tab Hunter Show.') Lang shot Blue Gardenia in twenty days between 28 November and 24 December 1952. (One of the reasons he was able to keep to this schedule is because of his deployment of a new crab dolly which allowed the camera to be moved around the set on rubber wheels rather than by the laborious process of having tracks laid out on the set. This crab dolly results in several long takes, including one shot at the Chronicle newspaper which lasts a minute-and-a-half.)

Yet despite the niggardly working conditions and the obvious limitations of the material, Lang manages to make Blue Gardenia his own, and he does so not by transcending the banality of the material but by giving this banality a thematic (dare I say, philosophical) significance. The Los Angeles of Blue Gardenia is presented as a series of dreary interlocking social and economic spaces subject to the logic of capitalist consumption, most memorably condensed in Crystal's (Ann Sothern) preview of her hot date with her ex-husband: "drive-in dinner, drive-in movie, and afterwards we go for a drive." Every character, every act (including murder) is caught within these mirror duplications, this infinite regress of commodity forms. Casey Mayo (Richard Conte), the star reporter at the Chronicle and the film's ostensible hero, is introduced simultaneously in the flesh, as he rushes to a meeting at the West Coast Telephone Co., and as image: as Mayo stands in the background waiting to catch the elevator we see his photograph which accompanies his newspaper column in the foreground. Later, Norah Larkin (Anne Baxter), the film's heroine, will also be seen — through dissolves — as both an image and as flesh-and-blood character.

Mayo's behavior, moreover, links him not only to the eventual murder victim Harry Prebble (Raymond Burr) — Mayo and Prebble are two bachelors on the prowl — but to the boyfriend who dumps Norah via a 'Dear John' letter. These correspondences between characters are established not only through details of mise en scène (Casey has a little black book, Prebble claims that he has collected "more phone numbers than the telephone company"; they each have installed in their bachelor pads a private bar) but through framing, camera movement and — in the case of Mayo with Norah's ex-fiancé — the use of voiceover. Compare, for instance, the way that Lang shoots the scene of Norah being dumped on her birthday with the scene of Norah reading Mayo's 'Letter to an Unknown Murderess.' Lang establishes these two scenes and these two males as parallel. By doing so we are cued to see things that the characters remain blind to: not only Casey's sliminess (he tells Al, his photographer sidekick, "I want to be the guy to nail her [the murderess]") but also Norah's persistent willingness to be misled, to be duped.

Norah's interchangeability with the other female characters is evident from the beginning. In fact, it is Crystal, one of Norah's two roommates, who first catches the eye of both Mayo and Prebble (and Lang's roving camera). And it is Crystal again whom Prebble thinks he is speaking to on the telephone and asking out for dinner and drinks. Norah fills-in for Crystal and why not? They are both blondes with similar body types and hair color (as are the other primary female characters: Sally and Rose). Is this not the significance of the dissolve from Prebble's sketch of a generically attractive young woman posed in a black evening gown to Norah standing in the exact same pose and wearing a black Taffeta gown? Here a representation of feminine allure actively becomes Norah, or is it the other way round? Norah puts on this gown because it is a special occasion (it is her birthday and she has a letter from her soon-to-be-ex-boyfriend waiting to be read) but this dissolve serves — like the other doublings — to undermine the character's individuality. Sally looks at Norah in her new gown and says 'I'm glad you bought black. It will look good on any of us.'

And this sense of de-individuation will only increase as the film proceeds. When Mayo interviews the blind flower seller who sold a blue gardenia to Prebble's murderess the night that he was killed, her daughter surmises that the murderess's dress, already identified by her mother as taffeta, must be black since "that's the fashion this season." The logic of her reasoning is never called into question, and in fact it doesn't need to be since it is the color of Norah's dress (and, hence, we are led to assume here that it was exactly its status as the latest fashion that led Norah to buy it in the first place). Later, when one of the young cub reporters at the Chronicle asks Mayo how he knows that the murderess is beautiful — since this is how he has described her in his column — Mayo says "they're always beautiful." And it is true, she is beautiful. Norah's role throughout is thus simply to fill-in-the-blanks of the plot with herself. (The only moment when Norah demonstrates any true awareness of her plight comes when Mayo asks her if she is a LA girl and she says "No, I live here but it's not my home.")

What The Blue Gardenia seems to signal finally is the demise of film noir — a genre which Lang helped establish (M [1931]) and refine (Women in the Window [1944], Scarlet Street [1945]) — and its possibilities of nocturnal passion and existential striving. Noir, in this sense, can be seen as one of the final attempts - alongside another form of artistic expression of the period, abstract expressionism — to forestall the processes of reification at work in popular culture. The low-key chiaroscuro lighting of noir is moodily evoked several times in The Blue Gardenia (and, in fact, the cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca also shot Jacques Tourneur's noir classic Out of the Past [1947] as well as Tourneur's Cat People [1942] and I Walked with A Zombie [1943]) but it is supplanted through the course of the film by the harsh glare of television with its preference for flat, overhead lighting. This evisceration of the shadow world of noir finds its musical counterpart in Lang's juxtaposition of Wagner's 'Liebestod' with Nat King Cole's 'Blue Gardenia' (!). The former becomes the clue which allows Mayo to improbably solve the crime. Sitting in an airport lounge with Al waiting to fly off on their next assignment — "Front row seats at the next H bomb blast" — he suddenly becomes aware of Wagner being piped in on the airport speakers. He asks Al "What's that?" Al responds "Music. They can everything these days." Wagner's death-haunted (yet, canned) music will play through the next couple of scenes until the real murderess is unmasked. Then, in the final scene, a chord from Wagner will sound only to resolve itself ... in bouncy movie music which accompanies the 'happy ending.' The musical resolution, we might say, is a different kind of death knell, another form of death than the one promised by Wagner and noir. What we have in The Blue Gardenia is a death-in-life in which we can no longer tell whether the life we live is our own or just an episode from a television series. In this context the closing shot of a LA freeway concrete overpass — a repetition of the film's opening image — takes on an unexpected relevance and poignancy.

Sam Ishii-Gonzalès teaches aesthetics and film history at New York University and the Film/Media Studies Program at Hunter College. He is the co-editor of Hitchcock: Centenary Essays (BFI, 1999) and has published essays on Luis Buñuel, David Lynch, and the English painter Francis Bacon.

The Blue Gardenia (1953) is a late thriller in the film noir style. The Blue Gardenia is a beautiful movie. Every shot is well imagined. The film involves the viewer in its storytelling, and sweeps one along.

Mass Media

The mass media dominate much of The Blue Gardenia, just as they do other Lang films. There are five media with a prominent place in the story:

1) The phone system. Two of the heroines of the film work as operators at the phone company. The large switchboards, with their thousand of interconnecting wires, are a powerful visual metaphor for all the interconnections of the modern communications grid. Lang returns to the phone company again and again throughout the film. The switchboards are always above the heads of the characters, dominating the upper halves of the compositions. This visual arrangement suggests the power that mass media have over us, controlling our lives. As usual in Lang, the technology behind the media is stressed: we see the wires and boards.

2) The newspapers. The hero of the film, played by Richard Conte, is a newspaper columnist. It is his column that especially seems to pursue the heroine. His influence is much more powerful than the police, and his ideas are more intelligent, both facts being repeatedly stressed in the film. Conte has an assistant in the film, but otherwise he is the only main newspaperman on the story. Later, in Lang's While the City Sleeps (1956), a whole slew of competing media types will pursue a criminal. This film will be even more scathing about the role of the press in tracking crime. Even here, the portrait of Conte is ambiguous. By the end of the film, after meeting Anne Baxter, he develops into a compassionate hero. But his early role in the film includes disseminating in his column a portrait of the killer and her character and motives that we know to be substantially different from the facts in the case. This gives a sinister edge, and a criticism, not so much of Conte's character personally, but of the press itself.

Lang also looks at the machinery of mass distribution of the newspapers. We see the city room at the paper, see the papers being delivered to newsstands, newsboys hawking them, watch ordinary people read the articles. It is a whole course in the technology and organization of a mass medium.

3) Phonographs. Music plays a key role in the film. Nat King Cole appears in person to sing the title song, "The Blue Gardenia", at the restaurant. Later, records of his song turn up in the film. Records of music playing on the turntable have a key role in the murder plot. Eventually, we wind up in a record store, which sells such music to the masses. We also see juke boxes, and canned music in restaurants, treated as a new technological development.

One of the records that is heard is the Liebestod, from Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde. This plays a somewhat sinister role in the plot. Lang, with his background in German culture, would have overwhelming feelings about Wagner, many of them negative after Wagner's use as near official composer of the Nazi regime. Lang is also the director of Die Nibelungen (1924), one of the two main modern retellings of the medieval saga, along with Wagner's Ring Cycle of operas; so in some ways Lang is Wagner's opposite number. Oddly enough, the dialogue of the film never identifies the music.

4) Photographs. Baxter has dinner with her boyfriend's photograph, while he is off in Korea. This shows how photographs play a role in modern life. Lang is quite tender about all the problems caused by the Korean War. One of the main subjects of his American films was all the suffering that war brings to civilians. One sees this in Ministry of Fear, Cloak and Dagger and American Guerrilla in the Philippines. The Blue Gardenia is one of the few non-war films to even mention the Korean War.

5) Monitoring. When Baxter calls Conte, one person listens in and records the call, while his other assistant has the call traced. It is a demonstration of the power of modern technology to monitor communication. A policeman even shows up on the other end of the phone, further conveying the idea of high tech surveillance. Everyone in L.A. seems to be watching everybody else, and reporting what they learn to the police. The paranoid effect is closer to Nazi Germany than to modern America.

Sociology

Nat King Cole plays the first black role I can remember in any of Lang's modern-day films. He behaves with complete dignity, as he always did: it is a completely non-stereotyped portrayal. It is good to see black people in Lang's films. One also recalls the kind hearted Jewish couple in You and Me (1938) who look after Sylvia Sidney. When Lang came to America, he became far more progressive on racial issues than he was in Germany. One suspects that the rise of the Nazi party gave Lang serious pause, and caused him to wake up and take a stand on racial equality.

The Blue Gardenia is the first of Lang's films to be set explicitly in Los Angeles. His earlier crime stories tend to have a New York City setting, despite being filmed in Hollywood. This is perhaps an artifact of budgeting. The Blue Gardenia has a low, low budget, and perhaps it was just cheaper to admit that everyone was in LA, where after all most of Lang's films were shot. But it also opens visual possibilities to Lang not present in his earlier films. The LA police with their black leather jackets are consistent with all the other black leather uniformed characters in Lang's previous work. The scene where the heroine is confronted by one while burning an incriminating dress in her incinerator is a visually striking scene. The combination of fire and night seems especially Lang like, conjuring deep, archetypal images.

A blind person forms an important witness here, just as in M. The actress who plays the blind woman is Celia Lovsky. Lovsky was at one time married to Peter Lorre, and Lang would have known her from their European days. Lovsky is one of my favorite performers; I've been a big fan of hers since she appeared in "Amok Time" (1967) on the original Star Trek.

Newspaperman Richard Conte in The Blue Gardenia and police sergeant Glenn Ford in The Big Heat each have assistants. Neither of the assistants ever does anything of significance. Both are just there, perhaps to indicate that the men have achieved a certain rank. Ford's assistant Hugo is in police uniform, while Ford is in plain clothes. This is typical of Lang, in which uniformed characters are plentiful, but rarely have a significant role.

Both men also have bosses. Both bosses keep trying to remove the heroes from the central crime problem of the film. Conte's does this unmaliciously, as a plot device; Ford's is under pressure from corrupt superiors, and is much more serious threat to the hero. Conte's boss wants him to travel to an H-Bomb test; this reminds us that Lang made Cloak and Dagger (1946), and is deeply worried about the nuclear age.

Architecture

The apartment shared by the three heroines of The Blue Gardenia recalls those in Scarlet Street. The curtained doorway to the entrance recalls the vestibule halls of both apartments in Scarlet Street. The visual treatment of both films' apartments is especially close. Lang explores every nook and cranny of the apartments in both films, shooting from every angle. In both films, the apartments become major characters in the story. One always wonders what new perspective will be revealed next. Lang will sometimes shoot a sweeping vista, showing a wall from an entire length of the apartment. Then he might cut to a close view of a single alcove, or wall segment with a table.

In both films, it is sometimes hard to tell exactly where one is in the apartment. There is very little camera movement, and Lang's camera will suddenly materialize at a particular point. It will show us a well composed view, with everything within the view crystal clear; but where this segment of the apartment is will be completely unclear to the viewer. Lang himself used scale models of his sets to compose his films. Looking like doll houses, Lang could plan every camera angle long in advance of the actual  shooting. This meant that he was deeply familiar with his sets, knowing them at a profound visual level. I have found that it really helps me to try to construct a similar diagram. Repeated viewings of a film, taking advantage of the pause button on the VCR, allow one to try to reconstruct the shape of the apartments, and the position of each shot. Far from spoiling my pleasure in the film, this activity deepened it. Lang's camera placements and set design are the result of deep thinking about visual relationships. The more intensively the viewers look at these things, the deeper the actual pleasure. shooting. This meant that he was deeply familiar with his sets, knowing them at a profound visual level. I have found that it really helps me to try to construct a similar diagram. Repeated viewings of a film, taking advantage of the pause button on the VCR, allow one to try to reconstruct the shape of the apartments, and the position of each shot. Far from spoiling my pleasure in the film, this activity deepened it. Lang's camera placements and set design are the result of deep thinking about visual relationships. The more intensively the viewers look at these things, the deeper the actual pleasure.

Lang's visual style is genuinely architectural, to use the word employed by Andrew Sarris. One can compare Lang's compositions to Hathaway's. In Henry Hathaway's Kiss of Death, every shot forms a geometric background. Hathaway likes to film his characters against vertical lines and rectangular regions. Hathaway is as geometrical as Lang, but far less architectural. In Lang, one is always conscious that one is seeing a background of the apartment. One sees a group of walls at a certain angle, together with the space between them. One always sees a continuous section of the apartment walls. This forms both a 2D geometric pattern on the screen, and a 3D piece of space, that the viewer can imagine walking around in, and otherwise occupying as a piece of spatial area. Hathaway gives equal time to non-architectural features in his compositions: two standing policemen might form parallel vertical lines framing his hero, or a shadow on the wall might form a geometric shape. In Lang, the background is much more purely architectural.

Raymond Burr's apartment in The Blue Gardenia looks more like that in The Woman in the Window. Both are more upscale, and look like seats of decadent, self-indulgent behavior. Both have large mirrors over their fireplaces, as the center of attention. The mirror goes down the sides of the fireplace in The Woman in the Window; the one in The Blue Gardenia does not, but the corresponding space is taken up by two tall plants. These plants form a similarly striking composition. The foliage of these plants is really excessive by any standards; it calls attention to itself, and suggests an out of control sensuality.

Another common feature of the Burr apartment and Joan Bennett's in The Woman in the Window: the sense that the living room contains a large open space. Unlike the much more hemmed in spaces of the heroine's apartment, one senses that the living room is a large, open, nearly square area. Often Lang shoots this room to emphasize its open quality. His camera will be quite far back, and we will see this large open area in which the characters can move around. This sense of space does many things. It suggests more money and more luxury. It also makes the heroes' lives look less determined by their environments here. There is also a completely different psychology about these spaces. Both are places where the protagonists visit, and foolishly decide to get involved in illicit relationships.

The vestibule of Burr's apartment also looks like that of The Woman in the Window. One difference: Burr lives on an upper floor, and Baxter descends to the vestibule via a staircase, while Joan Bennett's apartment is on the ground floor. There is also a staircase in her vestibule, but it leads on up to other tenants' apartments. Both vestibules are places of maximum emotional stress for the protagonists, following the killing. There are the locus of escape for the heroes.

The restaurant in The Blue Gardenia recalls to a degree the one in Clash By Night. Both are open, full of various rooms, and resemble a maze the characters are entering, a zone where emotions run high and from which it will not be easy to escape. Each room through which the heroine passes seems to get her deeper and deeper into the clutches of Raymond Burr. In some ways The Blue Gardenia resembles an anthology of Lang's previous films, a place where he resurrected techniques from his earlier movies, and gave them another chance. The restaurant also has a tilted mirror over Nat King Cole, giving us a dual view of his performance. This is typical of Lang's fascination with mirrors. Here, as elsewhere, we get to see a character in two views in the same shot. It was often the hero that received the mirror treatment in early Lang films, such as Spies; here it underscores Nat King Cole's importance in the film.

Lang's architectural approach to composition sometimes associates characters with architectural features. When Baxter makes her courageous trip to the newspaper, Lang uses a striking composition where the elevator door is in turn seen through he newsroom door. First we see the geometry without Baxter, waiting for her. Later we see her arrival, deep in the image, then walking through the two doors towards the camera. The name of the newspaper appears and disappears in shadows over the top wall of the image. The whole dark shot recreates the newspaper as an institution, one made up out of shadows and darkness, into which Baxter is entering, a small figure.

Similarly at the gas station, Lang includes a scene with a gas station attendant and a policeman. The left side of the screen includes the attendant and the gas pump, the right side the cop and the telephone booth he is monitoring. Each gets associated with one of these two architectural features. The shot is face on, and carefully composed. Both the booth and the pump become rectangular regions in the composition. Later we see the cop in the phone booth, similarly head on. The images deeply combine him with this architecture. When the policeman stoops to pick up a handkerchief, the camera travels up with his body, giving us a close up of his uniform.

Lang includes a pan of Baxter wandering city streets, after her phone call. She goes through different vertical zones of buildings, each illuminated in a different style, light or dark. The shot turns into a series of architectural images.

Pursuing the Criminal

Many of Lang's films involve a manhunt for a criminal. The one in The Blue Gardenia is closest to The Woman in the Window, as has been pointed out by other commentators. In both cases, the protagonist is innocent, having acted in self defense. Fear of scandal and of being charged with a crime prevents them from coming forward. Anne Baxter's character gets a more civilized treatment than any who have gone before her, however. She herself reaches out to pursuer Richard Conte, and a love story ensues. Perhaps because Baxter's character is female, she gets a gentler treatment than the others, and one centering more on love than on fear. This suggested motivation is a bit chauvinistic — must love always be a woman's domain? — but it also makes for an interesting story.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

DVD

|

Image Entertainment

|

|

Runtime:

|

88:14 min

|

|

Video:

|

1.31:1/4:3 Fullscreen

|

|

Bitrate:

|

6.25 mb/s

|

|

Audio:

|

English Dolby Digital 1.0 Mono

|

|

Subtitles:

|

None

|

|

Features:

|

None

|

|

DVD-Release:

|

11 April 2000

|

|

Chapters: 12

Snap Case

DVD Encoding: NTSC Region 0

SS-SL/DVD-5

|

The black-and-white picture is in fairly good condition. The source material is free of significant wear and contrasts are nicely detailed, with smooth blacks. The monophonic sound is fine. The 88 minute program is not captioned.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg) |

|

|

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)