|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

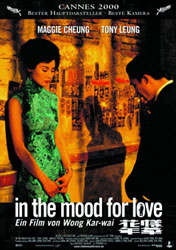

Hua yang nian hua

(In the Mood for Love)

|

|

|

| |

|

Hongkong / France 2000 - 97 Minuten -

Regie: Wong Kar-Wai

Produzent: Wong Kar-wai

Executive Producer: Ye-cheng Chan

Produktion: Block 2 Pictures Inc / Jet Tone Flms Production / Paradis Films

Drehbuch: Wong Kar-Wai (incorporating quotations from the writings of Liu Yi-Chang)

Kamera: Christopher Doyle, Mark Lee Ping-bin (Color, 1.66:1 Breitwand 35 mm)

Schnitt: Chan Kei-hap, William Chang

Musik: Michael Galasso; Shigeru Umebayashi ("Yumeji's Theme"); Nat King Cole ("Aquellos Ojos Verdes", "Quizas, Quizas, Quizas", "Te Quiero Dijiste")

Ton: Kuo Li-chi, Liang Chih-da, Tang Shiang-Chu (recordists)

Produktionsdesign: William Chang

Bauten: Man Lim-chung, Alfred Yau

Drehorte: Macao / Bangkok, Thailand / Cambodia (Buddhist temple of Angkor Wat)

Darsteller: Tony Leung Chiu-Wai (Chow Mo-wan), Maggie Cheung (Su Li-zhen), Lai Chin (Mister Ho), Rebecca Pan (Mrs. Suen), Siu Ping-Lam (Ah-Ping)

Premiere: 20 Mai 2000 (Uraufführung Cannes Film Festival) • 29 September 2000 (Hong Kong) • 30 November 2000 (deutsche Erstaufführung)

Auszeichnungen: British Independent Film Awards 2001 Best Foreign Independent Film • Cannes Film Festival 2000 Best Actor Tony Leung Chiu Wai; Technical Grand Prize William Chang, Christopher Doyle, Pin Bing Lee • César Awards 2001 Meilleur film étranger • European Film Awards 2000 Five Continents Award • German Film Awards 2001 Best Foreign Film

|

|

|

International Movie Database International Movie Database |

All-Movie Guide All-Movie Guide |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

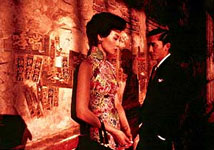

There is a recurrent sound of a sensual waltz that accompanies each encounter between Chow Mo-Wan (Tony Leung) and Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung) as they invariably cross paths in a crowded residential complex: the first is a polite glance as Mo-Wan leaves the room of a friendly card game; and then during the subsequent encounters on the steps of a noodle shop, where, often denied  dinner companionship by their spouses, they stop for a quick meal. One evening, Mo-Wan asks to meet Su Li-zhen in a restaurant, admires her purse, and asks where he could buy one as a present to his wife. She explains that it is a gift from her husband that was purchased during a recent international business trip, and is not locally available. Su Li-zhen, in turn, asks Mo-Wan about his tie, and he responds that it is a gift from his wife. The subtle, underplayed moment is a knowing confirmation of their own nagging suspicions about their spouses' infidelity. The two begin to rehearse scenarios in order to prepare themselves for the emotional confrontation: who initiated the affair; how to broach the subject of infidelity; how to react after the admission. When Mo-Wan decides to pursue a lifelong dream of writing a martial arts serial in order to pass the time, Su Li-zhen agrees to proofread his work. However, when their professional collaboration leads to an undeniable attraction, the two find themselves struggling with the shame and guilt over their own emotional betrayal.

Using graceful slow motion sequences and nostalgic music, Wong Kar-Wai juxtaposes the romanticism of a lost era with the unrequited longing of an impossible relationship in In the Mood for Love. Wong's highly stylized camerawork serves as a visual foil to the chaos of the meticulously structured mise-en-scène: the crowded living conditions, overly familiar neighbors, and imposing, uninvited guests reflect the claustrophobic, intrusive nature of traditional society. In contrast, the suffused colors of the empty restaurant and the long, reverse tracking shot of the hallway leading to Mo-Wan's creative retreat reflect the uninhibited freedom of their surfacing emotions. Furthermore, Su Li-zhen's seductively bold and exquisitely tailored high collared dresses manifest her paradoxical character: passionate, yet reserve; sensual, yet conservative. In essence, the visual dichotomy of the film serves as a reflection of the emotional turmoil that results from their innocuous alliance. In the Mood for Love is a subtly intoxicating and hypnotic film on love and longing, fate and destiny, connection and isolation.

Like the cologne of a past lover, In the Mood For Love inhabits our senses, fills our imaginations, and evokes the essence of romantic love without ever displaying its carnal side. The restraint with which director Wong Kar-Wai tells the story is, then, ironically masochistic. It would be easy for his two solitary protagonists, a young, dashing newspaperman Mr. Chow (Tony Leung) and his elegant next door neighbor Mrs. Chan (Maggie Cheung) to become lovers—easy because they live in 1963 Hong Kong where cramped communal living negates all privacy and personal space, and more significantly, because their respective spouses are carrying on an affair of their own. And while nothing sexual ever passes between the cuckolded pair, there’s an undeniable feeling that they are making love all the time, in the way they pass each other on the way to the noodle stands, the way her dress brushes against his knee, or the casual manner in which he places a dollop of mustard on her dinner plate. In the Mood for Love creates eroticism from the smallest details, magnifying them, contemplating them, before allowing them to be slowly re-absorbed into the humid, redolent air that surrounds them always. Like the cologne of a past lover, In the Mood For Love inhabits our senses, fills our imaginations, and evokes the essence of romantic love without ever displaying its carnal side. The restraint with which director Wong Kar-Wai tells the story is, then, ironically masochistic. It would be easy for his two solitary protagonists, a young, dashing newspaperman Mr. Chow (Tony Leung) and his elegant next door neighbor Mrs. Chan (Maggie Cheung) to become lovers—easy because they live in 1963 Hong Kong where cramped communal living negates all privacy and personal space, and more significantly, because their respective spouses are carrying on an affair of their own. And while nothing sexual ever passes between the cuckolded pair, there’s an undeniable feeling that they are making love all the time, in the way they pass each other on the way to the noodle stands, the way her dress brushes against his knee, or the casual manner in which he places a dollop of mustard on her dinner plate. In the Mood for Love creates eroticism from the smallest details, magnifying them, contemplating them, before allowing them to be slowly re-absorbed into the humid, redolent air that surrounds them always.

The movie’s setting belongs to a bygone age, and in the movie’s own words, "nothing that belongs to it exists anymore." That notion of romantic ethereality, of events so keenly lived but now gone forever, informs the movie’s entire structure, from the way shots are edited together to the sprawling geographical displacement that dominates the final half hour. In the movie’s early scenes, Wong and his editor William Chang frequently cut to black to suggest the early stages of recollection. People, events, smells come back to us in random pieces that pass over like warm puffs of air. We see Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan moving in. It’s crowded; furniture gets mixed up; people squeeze past each other in narrow, dim hallways. The protagonists greet each other formally, but there’s hardly any eye contact. As the movie settles in, those shots become more meditative, stretched out and slowed down, and are set to the insinuating violins of a Spanish love song that suffuses the already rich atmosphere with a kind of Latin moodiness (the film was shot in the Portuguese colony of Macau).

The protagonists, we can clearly see, are in tune with their sensual sides. She wears a devastating series of restrictive, floral print dresses that show no skin but which outline her form with sharp precision; he smokes a cigarette like the prototypical French New Wave anti-hero, all attitude and posturing. When their spouses run off together to Japan, we expect their formal attitudes to thaw, but instead they find solace in each other’s unapproachability. A revelatory scene at a diner becomes a conversation about handbags and ties: it’s a skittish dance around the unspeakable that acknowledges everything but verbalizes close to nothing. Repelled by their spouses’ indiscretion, they find themselves in a world where illicit sex mocks them at every corner. Mrs. Chan’s boss carries on an extra-marital affair between power meetings; in one scene, he asks her to choose a suitable birthday present for his mistress. Mr. Chow’s co-workers, as overweight and ungainly as he is lean and stylish, ask to borrow money so that they may visit a brothel. Our protagonists comply without protest, helping others commit that which they would never do.

Content to remain polite acquaintances, or maybe scared of turning into their errant spouses, Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan (they never address each other informally) become prisoners of their own good behavior. Their bottled-up sexuality plays tricks on their minds, inverting the chronology of crucial events. Her secret visit to his room takes place after he discovers her lip-sticked cigarette on his ashtray. And confrontations seem to occur before they actually happen: what we think is Mrs. Chan accusing her husband of infidelity turns out to be a dress rehearsal, with Mr. Chow as the stand-in. Imagination supersedes reality. Wong’s camera is in search of what it can’t see, that sweaty anticipation or elusive frisson that courses through us when romance, or the memory of it, is near. Approximating love’s incoherence, Wong’s sense of time progresses fitfully, impatiently and impulsively. A day occupies the same space as a week. As their relationship attenuates towards the inevitable, time takes even bigger strides. The final sequences, set in such places as Singapore and French Cambodia, are separated by months, then a year, and then three years. Love recedes exponentially; it never fully disappears, but, as Mr. Chow states in the end, grows increasingly "blurred and indistinct" with time. Panning across ancient ruins that might symbolize love long since abandoned, the final scene feels unnecessary. Every second of the movie has been an act of remembrance, a sifting through of artifacts from a dead era.

Beautiful without being fatuous, In the Mood for Love displays occasional flashes of cynicism. "What would I be if I wasn’t married," he asks, and her reply is "Maybe happier." Their jaded temperament, while never angry, cools the movie’s overripe sensuality, shading it with self-doubt and indecision, and adds new dimensions to the movie’s ravishing surface beauty. The cinematography by Christopher Doyle and Mark Li Ping-Bin becomes almost tragic as the would-be lovers fumble in the shadowy Hong Kong alleyways. Their bodies partially concealed, they never reveal themselves fully to each other. The set design and costumes evoke sixties sexual arrogance and often have double meaning, from the red curtains that guide them to a sexual encounter that never happens, to Mrs. Chan's dresses which are dyed with intense, exotic patterns but whose high collars and low hemlines fit her like chastity gear. At once exuberant and pessimistic about love, Wong Kar-Wai never plays us the titular song, as he did in his previous film Happy Together. But this denial, like the other forms of denial in this gorgeous and intelligent movie, only heightens that which isn’t physically experienced. With patience and empathy, Wong Kar-Wai distills love, sexual, romantic or otherwise, to its barest, most basic ingredients.

Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love:

Like a Ritual in Transfigured Time

In Dream Time

It is by no means coincidental that the two most celebrated Chinese-language films of the last two or three months – Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love (2000) – hark back to old genres and times past. Some grand design of time has brought the films about. Both directors and their films recollect childhood memories of pleasures induced from going to the cinema. Both men are roughly of the same generation (Lee was born in 1954; Wong in 1958), and have come of age as directors at about the same time: this, above everything else, appears to have informed their choices of genre. In the case of Ang Lee, the director's own memories of watching martial arts pictures spawned boyhood fantasies of a China "that probably never existed." (1) Watching the pictures of the wuxia (sword and chivalry) genre throughout his formative childhood days evoked a dreaming time for Ang Lee " his his film being in his own words, "a kind of dream of China". (2) Both Ang Lee and Wong Kar-wai, each in their own ways and working in radically different genres, have tried to duplicate this kind of "dream time" in their respective movies. It is by no means coincidental that the two most celebrated Chinese-language films of the last two or three months – Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love (2000) – hark back to old genres and times past. Some grand design of time has brought the films about. Both directors and their films recollect childhood memories of pleasures induced from going to the cinema. Both men are roughly of the same generation (Lee was born in 1954; Wong in 1958), and have come of age as directors at about the same time: this, above everything else, appears to have informed their choices of genre. In the case of Ang Lee, the director's own memories of watching martial arts pictures spawned boyhood fantasies of a China "that probably never existed." (1) Watching the pictures of the wuxia (sword and chivalry) genre throughout his formative childhood days evoked a dreaming time for Ang Lee " his his film being in his own words, "a kind of dream of China". (2) Both Ang Lee and Wong Kar-wai, each in their own ways and working in radically different genres, have tried to duplicate this kind of "dream time" in their respective movies.

Wong's In the Mood for Love is a romance melodrama, which tells the story of a married man (played by Tony Leung) and a married woman (played by Maggie Cheung), living in rented rooms of neighbouring apartments, who fall in love with each other while grappling with the infidelities of their respective spouses whom they discover are involved with each other. The two protagonists are thrown together into an uncertain affair which they appear not to consummate, perhaps out of social propriety or ethical concerns. As Maggie Cheung's character says: "We will never be like them!" (referring to the off-screen but apparently torrid affair of their respective spouses). The affair between Cheung and Leung assumes an air of mystique touched by intuitions of fate and lost opportunity: is it a Platonic relationship based on mutual consolation and sadness arising out of the betrayal of their spouses? Is it love? Is it desire? Did they sleep together? Such ambiguity stems from the postmodern lining of the picture (its look as processed by Wong's usual collaborators, the cinematographer Chris Doyle and art director William Chang), which is more in line with Wong Kar-wai's reputation as a cool, hip artist of contemporary cinema.

However, there is a conservative core to the narrative that is quite unambiguous, clearly evident in the behaviour of the central protagonists, both of whom act on the principle of moral restraint. In this regard, the film reminds me of the 1948 masterpiece Spring in a Small City, directed by Fei Mu, the plotline of which is slightly mirrored in Wong's film. (3) In Spring, a wife meets her former lover and flirts with the possibility of leaving her sick husband. In the end, she falls back on the principle of moral restraint. The director Fei Mu was reputed to have ordered his players to act on the dictum "Begin with emotion, end with restraint!" As a result, the film ends on a note of moral triumphalism colored by a sense of sadness and regret, reinforcing the inner nobility of the characters – a theme which Wong regurgitates with the same sense of brevity and cast of subtlety. The soulful nobility of the characters in both films is a touching reminder of the didactic tradition in Chinese melodrama, where the drama serves to inspire one to moral behaviour – and when the actors are as beautiful as Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, the note of restraint is all the more poignant and all the more ennobling (the attractiveness of the characters preying on our own natural inclinations or baser instincts building up a kind of suspense but finally leading to an anticlimax that is as close to a philosophical statement as Wong Kar-wai has ever got his audience to). However, there is a conservative core to the narrative that is quite unambiguous, clearly evident in the behaviour of the central protagonists, both of whom act on the principle of moral restraint. In this regard, the film reminds me of the 1948 masterpiece Spring in a Small City, directed by Fei Mu, the plotline of which is slightly mirrored in Wong's film. (3) In Spring, a wife meets her former lover and flirts with the possibility of leaving her sick husband. In the end, she falls back on the principle of moral restraint. The director Fei Mu was reputed to have ordered his players to act on the dictum "Begin with emotion, end with restraint!" As a result, the film ends on a note of moral triumphalism colored by a sense of sadness and regret, reinforcing the inner nobility of the characters – a theme which Wong regurgitates with the same sense of brevity and cast of subtlety. The soulful nobility of the characters in both films is a touching reminder of the didactic tradition in Chinese melodrama, where the drama serves to inspire one to moral behaviour – and when the actors are as beautiful as Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, the note of restraint is all the more poignant and all the more ennobling (the attractiveness of the characters preying on our own natural inclinations or baser instincts building up a kind of suspense but finally leading to an anticlimax that is as close to a philosophical statement as Wong Kar-wai has ever got his audience to).

Whether or not one sees In the Mood for Love as a film about sexual desire or alternatively, about moral restraint, there isn't that much more to the plot. It lives up to its English title as a veritable mood piece, and is essentially made up of rather passive and variable substances: the characters and their interchange of feelings that are nothing more than fleeting moments of time. Added to all this is Wong's dense-looking mise en scène that combines the acting, art direction, cinematography, the colours, the wardrobe, the music, into an aesthetic if also impressionistic blend of chamber drama and miniature soap opera. Wong's key elements – what older critics might call "atmosphere" and "characterizations" – are thus grounded in abstraction rather than plot, and it's hard to think of a recent movie that offers just such abstract ingredients that are by themselves sufficient reasons to see the picture. But it is precisely this quality of aesthetic abstraction that makes up an ideal dreamtime of Hong Kong, which is Wong's ode to the territory.

The Melodrama of Mood

The English title itself, of course, strikes the key to the picture, suggestive of foreplay or a kind of mind-massage. What Wong Kar-wai does for an hour and a half is to butter up his audience for two or three levels of mood play: a mood for love, to begin with; but even more substantially, a mood for nostalgia, and a mood for melodrama. In Wong's rendition of the melodrama, we have a romance picture that works mainly as a two-hander chamber play, illustrated by contemplative snippets of popular music that also help to recreate the ambience of Hong Kong in the 1960s. The elements of nostalgia and melodrama that play on our feelings are Wong's way of paying tribute to a period and to a genre. The Chinese melodrama (known in Chinese as wenyi pian) is traditionally more akin to soap opera – a form that assumes classic expression in the '60s with the rise of Mandarin pictures from both Hong Kong and Taiwan (particularly adaptations from the literary works of the author Qiong Yao, often starring Brigitte Lin). feelings are Wong's way of paying tribute to a period and to a genre. The Chinese melodrama (known in Chinese as wenyi pian) is traditionally more akin to soap opera – a form that assumes classic expression in the '60s with the rise of Mandarin pictures from both Hong Kong and Taiwan (particularly adaptations from the literary works of the author Qiong Yao, often starring Brigitte Lin).

The terminology "wenyi" is an abbreviation of wenxue (literature) and yishu (art), thus conferring on the melodrama genre the distinctions of being a literary and civilized form (as distinct from the wuxia genre, which is a martial and chivalric tradition). Wong seizes on the literary or "civilized" antecedence of the genre to water down the soap opera tendencies that were characteristic of '60s melodramas. (4) Wong's interest in the genre is not so much narrative as associative. For instance, he equates the melodrama with the '60s, a period that for the director, yields manifold allusions to memory, time, and place. "I was born in Shanghai and moved to Hong Kong the year I was five (i.e. around 1963). ... For me it was a very memorable time. In those days, the housing problems were such that you'd have two or three families living under the same roof, and they'd have to share the kitchen and toilets, even their privacy. I wanted to make a film about those days and I wanted to go back to that period ...", Wong says. (5)

The melodrama genre itself becomes an apt metaphor for the '60s, with many films of the period dealing with just such housing problems and families living under the same roof as Wong speaks of. The invocation of wenyi pian carries a sense of period and place. The Chinese title, Huayang Nianhua (translated in the subtitles as "Full Bloom" but more accurately meaning "those wonderful varied years"), is more suggestive of period nostalgia and the Shanghai association, pointing to an iridescent, kaleidoscopic age of bygone elegance and diversity (and it is actually the title of a Chinese pop song from the '40s which we hear played on the radio, sung by the late singer-actress Zhou Xuan who popularized the song in a 1947 Hong Kong Mandarin movie). In Wong's hands, the genre itself and the period of the '60s is a stage of transfigured time that isn't fixed diachronically. His '60s happens to coalesce around other synchronic recollections of the memorabilia of earlier periods (such as the '40s or the '50s), through the evocations of popular culture as a whole that largely recalls the glories of Shanghai: in music (citing the songs of Zhou Xuan, for example), in fashion (the cheongsam), novels (the martial arts serials that Tony Leung writes with input from Maggie, that recall the methods of the "old school" writers of martial arts fiction in '30s and '40s Shanghai), and the cinema (the unstated allusion to Spring in a Small City).

In watching the film unfold, the audience itself is partaking in a ritual in transfigured time (to borrow the title of a 1946 Maya Deren film (6)), and each member of the audience, depending on their ages, could in theory go as far back in time as they wish to the moment that holds the most formative nostalgic significance for them. Of course, Wong's skill in recreating Hong Kong of the '60s seems so assured and so transfixed to those of us born in the post-war baby-boom years who grew up in the '60s that it is more than enough to recall nothing but the '60s (with the rise in our consciousness at the time of Western culture and accoutrements, plus the efforts to blend East and West, as evoked by the references to Nat King Cole's Spanish tunes, Japan, electric cookers, the handbag, Tony Leung's Vaselined hair, eating steaks garnished by mustard, and eating noodles and congee in takeaway flasks). East and West, as evoked by the references to Nat King Cole's Spanish tunes, Japan, electric cookers, the handbag, Tony Leung's Vaselined hair, eating steaks garnished by mustard, and eating noodles and congee in takeaway flasks).

So successful is Wong's recreation of the past that we tend to forget that he has only shown us the bare outlines of Hong Kong in 1962 (the year when the narrative begins). Wong has created an illusion so perfect that it seems hardly possible that the director has got away with really just the mere hints of a locality to evoke time and place (the film was shot in Bangkok rather than in Hong Kong with the feeling perhaps that the former could better convey the idea of transposed time, and not so much to capture 'authentic' details of the seedy alley ways and sidestreets, through which the protagonists pass or meet each other, that have supposedly vanished from modern Hong Kong). In other words, Wong Kar-wai has successfully transfixed his audience in a dreamtime without the necessary big-budget frills so that it actually seems a bit too dissociative to think of In the Mood for Love as a dreamtime movie. It doesn't, for example, indulge in the kind of overt symbolism such as one may associate with Dali's famous painting "The Persistence of Memory" where we see time pieces melting in a desert-like landscape, symbolizing time lost. I mention Dali's painting because in Wong's films, we do see persistent shots of clocks in what has now become the characteristic style of Wong Kar-wai (being so persistent, they actually invoke a surreal sense of time melting away, as in the Dali painting): those scenes in In the Mood for Love where the camera dollies down from a giant Siemens clock hanging overhead in Maggie Cheung's workplace to catch Maggie in a pensive moment. In Wong's deliberative manner, this is exactly the moment that would conjure up the '60s in his body of work, with the same motif and the same actress (indeed, essentially the same character) from Wong's key work in the early phase of his career Days of Being Wild (1990), also set in the '60s.

A Literary Vision

Such visual motifs are the obvious affirmations of Wong's style, denoting his preoccupations with time and space. However, in keeping with his theme of moral restraint, Wong himself appears to show a much more restrained hand in delineating his visual style, which seems less semaphoric and more attuned to the purposes of a narrative, however slight that narrative may appear to be. The film may function basically as a mood piece, with much to wonder at in terms of visual splendours, but there is no visual  motif that goes astray. In the Mood for Love is a virtual cheongsam show, for example, and who among the Chinese of the baby-boom generation could fail to be moved by the allusive and sensual properties of the body-hugging cheongsam (or qipao in Mandarin)? The array of cheongsams worn by Maggie Cheung is Wong's cinematic way of indicating the passage of time, but Wong also milks it for its erogenous impact on the mind and soul. Maggie Cheung clad in the cheongsam is surely every Chinese person's idea of the eternal Chinese woman in the modern age, evoking memories of elegant Chinese mothers in the '50s and '60s (when the gown was still in fashion) as well as memories of the Chinese intellectual female still bonded to tradition (recalling the image of the writer Eileen Chang, or Zhou Yuwen, the character played by actress Wei Wei in Spring in a Small City). motif that goes astray. In the Mood for Love is a virtual cheongsam show, for example, and who among the Chinese of the baby-boom generation could fail to be moved by the allusive and sensual properties of the body-hugging cheongsam (or qipao in Mandarin)? The array of cheongsams worn by Maggie Cheung is Wong's cinematic way of indicating the passage of time, but Wong also milks it for its erogenous impact on the mind and soul. Maggie Cheung clad in the cheongsam is surely every Chinese person's idea of the eternal Chinese woman in the modern age, evoking memories of elegant Chinese mothers in the '50s and '60s (when the gown was still in fashion) as well as memories of the Chinese intellectual female still bonded to tradition (recalling the image of the writer Eileen Chang, or Zhou Yuwen, the character played by actress Wei Wei in Spring in a Small City).

Much more significant, in my opinion, than all these visual configurations is Wong Kar-wai's predilections for covering his ground with literary references. It is often forgotten that Wong is a highly literary director, and part of the magic that he wields in movies like Days of Being Wild, Chungking Express (1994) and Ashes of Time (1994) is the consummate way with which he induces his audience to auscultate to his narratives. The monologues and voiceovers of those films are some of the most literary pieces to be heard in Hong Kong cinema. Of late, Wong has taken to inserting passages from books as inter-titles studding the course of the film, somewhat in the manner of silent movies, or in the manner of epigraphs in essays – a practice seen in Ashes of Time (where he quotes passages from the book by noted martial arts writer Jin Yong that was the source of his screenplay), and now in In the Mood for Love where he quotes lines from a 1972 novella, Intersection, by Liu Yichang, a Shanghainese expatriate writer living in Hong Kong. Gone is the voiceover narrative or the multiple monologues that he ascribes to each of his characters (finding classic expression in Days of Being Wild). The story of Intersection, the Chinese title of which is Duidao, tells of the way in which two characters' lives – strangers to each other – appear to intersect in ways apparently determined by the nature of the city, and the structure of the novella provides a direct form of inspiration for Wong's use of the intersecting motif in In the Mood for Love.

The influence of Liu Yichang's story cannot be underestimated so taken by the story has Wong been that he has actually put out an ancillary product in the wake of the film's release in Hong Kong last year: a book of photographs and stills from the film illustrating an abridged English translation of Liu Yichang's story. It's a curious kind of book, seemingly without any theme or focus, which actually contains a hidden title Tête-bêche: A Wong Kar-wai Project – the intersecting motif that makes up Wong's narr ther films, notably Days of Being Wild, Chungking Express, Ashes of Time, and Fallen Angels (1995), which are narratives of parallel stories, finally finds its mature expression in In the Mood for Love where the motif assumes a diacritical mode. The poetic nature of Wong's images and his style stems from this literary conceit, and the serial-like connotations of Chinese literature where the chapters intersect with one another (the zhang hui form) to build up the suspense of "what happens next". Wong's literary sensibility makes him unique among modern-day directors who would probably not have conceived of an ending whose spirit is basically literary in nature, embedded in storytelling and myth. This ending, taking place among the ruins of Angkor Wat (subconsciously calling to mind the ruins of Spring in a Small City which similarly endow a sense of melancholic nobility to the chief protagonist), is one of Wong Kar-wai's more conclusive and heart-stopping moments, filled with secrets that must never be revealed in a kind of compact between the director and the viewer, and finally infused with a sense of regret and Zen-like magnanimity.

Endnotes:

- Ang Lee, "Foreword," Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon: A Portrait of the

Ang Lee Film (New York: Newmarket Press, 2000), p. 7 Ang Lee Film (New York: Newmarket Press, 2000), p. 7

- Ibid.

- In interviews with the Western press, Wong speaks of being inspired by Hitchcock's Vertigo, as in this exchange with U.S. critic Scott Tobias published in The Onion, Volume 37, No. 07, pp. 1-7 March 2001: "I wanted to treat it like a Hitchcock film, where so much happens outside the frame, and the viewer's imagination creates a kind of suspense. Vertigo, especially, is something I always kept returning to in making the film."

- The soap opera tendency remains popular to this day, perpetuated largely by Japanese TV serials that are shown in the Chinese-speaking regions and also by long-standing traditions in Hong Kong and Taiwan cinemas (cf. the recent romance cycle in Hong Kong cinema, eg Sylvia Chang's Tempting Heart [1999], Jingle Ma's Fly Me to Polaris [1999], Wilson Yip's Juliet in Love [2000], Aubrey Lam's Twelve Nights [2000], etc.).

- Interview with Wong Kar-wai by Scott Tobias, The Onion, Vol. 37, No. 07, 1-7 March 2001.

- In Deren's film, a woman quite literally walks back in time, as symbolized by the opening shot of the filmmaker herself holding a thread that seemingly unspools in reverse, to mark the flow of the "thread of time" backwards as the chief protagonist follows this thread back in time.

- The last sentence in this passage is my own translation of the Chinese foreword that is separately printed on transparent paper inserted into the book which differs from the English text printed on the pages. The last sentence in the English text reads: "Tête-bêche can also be the intersection of time: for instance, youthful eyes on an aging face, borrowed words on revisited dreams." See Tête-bêche: A Wong Kar Wai Project (Hong Kong: Block 2 Pictures).

© Stephen Teo, Senses of Cinema, March-April 2001

Stephen Teo is the author of

Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions

(London: BFI, 1997).

He is currently engaged in his research project

for a Ph.D degree at RMIT University (Melbourne).

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

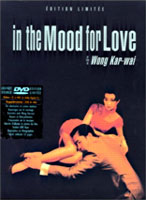

DVD

|

In the Mood for Love

TF1 Vidéo / Océan Films

Coffret Collector • 2-DVD-Set

|

| Länge: |

93:54 min (= 97 min PAL)

|

| Video: |

- 1:62:1/16:9 Anamorphic WideScreen

|

| Bitrate: |

|

| Audio: |

- Cantonese Dolby Digital 5.1 Surround

- Français Dolby Digital 5.1 Surround

- Español Dolby Digital 2.1 Surround

- Mandarin Dolby Digital 2.1 Surround

|

| Untertitel: |

- Deutsch

- English

- Español

- Français

- Italiano

- Hellenikê

- Nederlands

|

| Features: |

- DVD 1: Présentation des chansons et des musiques

- Bande-annonce originale

- DVD 2: 4 scènes inédites et fin altérnative, avec commentaire optionnel du réal (34 min)

- Interview avec Wong Kar-Wai (22 min)

- Les coulisses du tournage : making of et interviews (19 min)

- Promo-reel, teasers et bandes-annonces - 12 clips (16 min) : (avant Cannes, pour Cannes, sortie à Hong-Kong, sortie FR, sortie mondiale)

- Le tour du monde de Wong Kar-Wai (5 min)

- Featurettes: Les robes Qi Pao (2 min)

- Les coiffures (3 min)

- Le mah-jong (2 min)

- Biographies et filmographies du réalisateur, des acteurs et des principaux techniciens

- Commentaires sur la musique du film et la musique non utilisée

- Film publicitaire du disque

- Affiches et projets d'affiches

- Galerie photos n. 1 : les robes de Maggie Cheung

- Galerie photos n. 2 : les meilleurs moments du film

- Recettes de cuisine (soupe au sésame, nouilles sautées au poulet, won-ton au porc, etc.)

- Fiche technique et artistique

- Prix et récompenses

- Menu caché (accessible par la partie interactive de mah-jong) : Clip vidéo : "Hua Yang Nian Hua", Tony Leung et Niki (4 min)

- La leçon de cinéma de Wong Kar-Wai à Cannes 2001 en multi-angle (13 min)

- Avant-première du gala à Hong-Kong (14 min)

- Galerie photo d'images inédites

- 2 teasers et 2 bandes-annonces inédits (4 min)

- Projets de T-shirts pour agnes.b

- 2046 : le logo du titre du prochain film de Wong Kar-Wai

- DVD-Rom (DVD n. 2) : Fonds d'écran

- Economiseurs d'écran

- Livret de 12 pages

- Liens Internet

|

| DVD-VÖ: |

5 September 2001 |

|

Digipack Case

Chapter stops: 24

DVD Encoding: PAL Region 2 (France)

2x SS-DL/DVD-9 |

Picture: Possibly the best a Hong Kong film has ever looked on DVD the quality of this transfer is nothing short of stunning. TF1 Video has sourced a print for this transfer that despite the occasional white speck and some (standard for Hong Kong films) slight grain is in near perfect condition. Maintaining the original 1:66:1 aspect ratio and utilising anamorphic enhancement we are provided with an image that has a constantly high level of detail, vivid presentation of colours, and crucially black levels are nigh on perfect while the compression handles the various patterns and textures seen in the huge array of intricately detailed clothing with apparent ease. Top stuff.

Sound: For the main feature this has to be one of the best-specified DVD's available, with no less than 3 audio languages and 8 subtitle tracks this set will no doubt provide a language that most European and Asian customers can understand. For the main feature I opted for the original language track, Cantonese DD5.1 and rather surprisingly for a film of this nature the audio track makes full use of the soundstage. Mostly used to create a believable environment everything from rain to office chatter is projected perfectly around the room, and while the beautiful music is mostly confined to the fronts (but with stunning clarity), the final piece of music is spread out to consume the entire soundstage to stunning effect. Although this track will not offer demo worthy big bangs it will allow you to show off the subtlety that Dolby Digital is capable of. The English subtitle track is again of top quality, opting for an easy to read white font there are absolutely no problems with either spelling or grammar, instead the subtitles just flow with the superbly delivered dialogue although they can sometimes be a little fast when translating Chinese text.

Extras: Apart from a 12-page booklet (French language only) all extras are spread across the two discs. Firstly, I just have to mention that the Menu system on both discs is absolutely superb. After selecting your language preferences (after which all text/dialogue is presented where possible as you chose) a combination of superb visuals and enchanting music will take you through each of the discs superb navigation systems.

While the bulk of the extra features are contained on Disc 2 it is still worth taking a closer look at Disc 1. Contained within is the Original English Theatrical Trailer (in Non-Anamorphic Widescreen) as well as a text-based section entitled 'The Film and the Soundtrack'. Here you will find the first of many informative mini-essays on the various pieces of music heard throughout the film as well as links to the use of each piece of music in the film.

When you pop in the supplements disc you will again be asked to choose both your audio and subtitle language preference. Upon selection you will find yourself in a taxicab that has four locations, Guest House, Hotel, Restaurant and Local Businesses. Let me take you through what each section has to offer...

Guest House

Interview with Wong Kar-Wai: Making up for the lack of an Audio Commentary this 22 minute interview covers most aspects of the film with sufficient depth. Wong Kar-Wai speaks extremely good English and talks about the various subtleties that the Western audience will not understand, the problems with production, his visual style and choice of music, his selection of actors, the mood of the film and much, much more.

On Set Report: More than just your usual promotional fluff this 18 minute featurette takes us behind the scenes on the making of In the Mood For Love, going so far as to show the actors developing scenes (some of which are not present in the final cut) and their characters (including Tony Leung with a fake moustache that was lost for the final character). Also included are interviews with Wong Kar-Wai, Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung (and like the Director both leads speak very good English).

Music from the film: In this comprehensive look at the music used in the film you will find artwork from the various soundtrack albums, full track listings for the soundtrack, an 11 page analysis of the music from Joanna C.Lee, biographies for Michael Galasso (Original Music) and Shigeru Umebayashi (Yumeji's Theme), reflections on the music by Michael Galasso and Wong Kar-Wai, and finally a 20 second Music Spot. As an extremely important part of the film it is a joy to see that so much effort has gone into this highly informative section as you read about the various music used, the creation and selection of tracks as well as reflections on the music used.

Hotel

Deleted Scenes and Alternate Ending: Presented here are three deleted scenes (totalling 27 minutes) with optional commentary from director Wong Kar-Wai. It is fairly obvious why these scenes were cut as they would have been detrimental to the overall pacing of the film, they are however worth a look to see what alternative directions Wong Kar-Wai could have taken, and of course to see Tony Leung in what can only be called the 'Donnie Brasco' look! Wong Kar-Wai provides audio commentary for each of these deleted scenes in his native language (with English subtitles) and after listening to the commentary it becomes obvious why an audio commentary for the main feature just would not have worked. While he provides some interesting insights to the scenes in question his commentary barely lasts 5 minutes (in total!), which leaves most of the deleted scenes left to play out with their original audio intact. Also present in this section is an 11-minute alternative ending that again is interesting but, like the deleted scenes, was cut for the right reasons. No audio commentary is provided for the alternate ending.

In Front and Behind the Camera: In another selection of text based extra features we find a set of relatively in-depth biographies for the cast and crew as well as a set of Artistic and Technical credits. Also present are the DVD Credits, these really deserve a brief look just so you can see who created this wonderful set.

Multimedia Section: Pop this disc into your PC to find a selection of high quality wallpaper images (any picture in this review with a Jet Tone Films logo is a wallpaper image located on the disc), a screensaver, and of course the obligatory web-links.

Restaurant

Theatrical Trailers, Teasers and Promo Reels: Presented in Non-Anamorphic widescreen  are 16 minutes worth of Trailers consisting of a Promo-reel; Three Trailers for the Cannes Film Festival; Two Original Teasers; Original-Trailer; Three French Teasers; and a French Trailer. Utilising a mixture of Bryan Ferry's In the Mood For Love and the music used in the film this comprehensive set of trailers are worth a look just to see some more deleted scenes not present elsewhere on this set, and of course to get another fix of that music and superlative visual style! are 16 minutes worth of Trailers consisting of a Promo-reel; Three Trailers for the Cannes Film Festival; Two Original Teasers; Original-Trailer; Three French Teasers; and a French Trailer. Utilising a mixture of Bryan Ferry's In the Mood For Love and the music used in the film this comprehensive set of trailers are worth a look just to see some more deleted scenes not present elsewhere on this set, and of course to get another fix of that music and superlative visual style!

Posters and Concepts: In another comprehensive section we see both the final Poster artwork used around the world (including the unique Russian posters) as well as conceptual work from France, Korea, Germany and Hong Kong.

Wong Kar-Wai World Tour: Guaranteed to bring a smile to your face this 4 minute featurette follows Director Wong Kar-Wai and his main cast as they promote In the Mood for Love in several Asian countries (including Hong Kong, Japan and China). The whole thing is set to more of the engrossing soundtrack and is just a fun piece to watch as we see the various receptions the directors and cast receive.

Awards: To finish off this promotional section we see the list of awards that In the Mood for Love has (rightfully) amassed in its relatively short lifespan.

Local Businesses

Tailor: Here we see a 90 second featurette showing a lady being measured up for the Qi Pao style of dress that is used frequently in the film as well as a Tailor beginning to measure out the material. Also present is a small photo gallery showcasing the variety of quite exquisite dresses that Maggie Cheung wears throughout the film.

Hair Dresser: Here we see a lady having her hair put into one of the many styles seen within the film and quite frankly I am amazed she has any hair left after this rigorous session! This short clip truly makes you feel for the female actresses in the film who would have gone through this process every day of the shoot!

Noodle House: After watching the Interview with Wong Kar-Wai everyone should understand the significant role that the various foods seen within the film play. Here we are given (in what is a great idea) recipes for 4 of those meals (with ingredients and full detailed instructions) - Sesame Syrup, Pan-Fried Noodles, Won Ton and Chinese Ravioli. I have yet to try any of them out but I cannot wait to give them a go!

Postcard Kiosk: A large selection of photographs taken from the film.

Mah-jong Club: Included within is a one minute video clip showing the game of Mah-Jong being played (and it makes NO sense what-so-ever!!) as well as an Interactive game of Mah-jong that, with a little persistence (Hint: match 4 similar pairs of tiles in a certain order) reveals an elaborate scheme to access the hidden Easter Eggs menu....contained within are...

Easter Eggs: Unlike the rest of the disc everything in this section is provided in its native language only with no subtitles present in any language.

Tony Leung Music Video: Here we see a music video for the song 'Hua Yang Nian Hua' which is performed as a duet by Tony Leung and 'Niki'. Presented in Non-Anamorphic Widescreen and sung in Cantonese (I think!) it generally features Tony Leung smoking, and looking pretty darn cool, but that's it.

Premiere in Hong Kong: This 14 minute piece is a recording of the In the Mood for Love premiere in Hong Kong. To start with we see various celebrities arriving but then it goes into a series of speeches from various people including Wong Kar-Wai, Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung - all of which is sadly not subtitled so is of little use unless you understand the Chinese language used.

Room 2046: A series of photographs from cut scenes that focus on what happened (or not for that matter) in said room.

Two Unreleased Trailers and Two Unreleased Teasers: Exactly as the titles suggest these are a set of unused (French) Trailers/Teasers that are again presented in Non-Anamorphic widescreen and run for 5 minutes.

Concepts for T-Shirts by agnes b: Again, as the title suggests you will find 4 pieces of concept artwork for T-Shirts within.

2046: Title Logo: The logo for Wong Kar-Wai's forthcoming film scheduled for a 2002 release.

Film Master class: This 16 minute featurette is taken from the 2001 Cannes Film Festival where Wong Kar-Wai gave a 'Film Master class' presentation. This feature actually makes use of the multi-angle abilities of the DVD format but do not get too excited as it merely shows you the video as shot from three different cameras, so while it is multi-angle you do not really gain anything from it. Here we see Wong Kar-Wai (speaking in English) as he talks about the production schedule of In the Mood for Love, his method of shooting two films at once, his method of script writing and his forthcoming film, 2046, among many other interesting topics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg) |

|

|

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)