|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

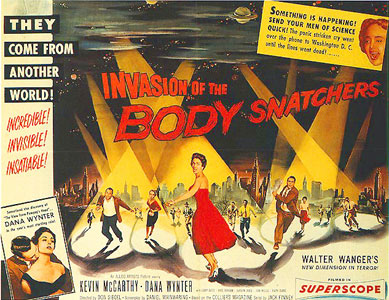

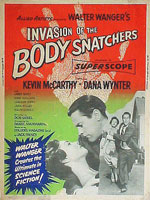

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| USA 1956 | 80 Minuten

Regie: Don Siegel Produzent: Walter Wanger Darsteller: Kevin McCarthy (Dr. Miles J. Binnell), Dana Wynter (Becky Driscoll), Larry Gates (Dr. Dan Kauffman), King Donovan (Jack Belicec), Carolyn Jones (Teddy Belicec), Jean Willes (Nurse Sally Withers), Ralph Dumke (Off. Nick Miller), Virginia Christine (Wilma Lentz), Tom Fadden (Ira Lentz), Kenneth Patterson (Stanley Driscoll), Sam Peckinpah (meter reader) Premiere: 5 February 1956 (USA) Drehbuch: Al La Velley (Hrsg.): Invasion of the Body Snatchers. New Brunswick [u.a.] 1989. Versionen: Originally released at 80 minutes; reissued in 1979 at 76 minutes, deleting the studio-imposed prologue and epilogue starring Whit Bissel and Richard Deacon. |

|

|||

|

Mark Deming, All Movie Guide

Invasion of the Body Snatchers, eine in 19 Tagen abgedrehte Low-Budget-Produktion (Kosten: nicht einmal 300.000 Dollar) von Walter Wanger nach einem 1954 erschienenen Serienroman (deutscher Titel: "Unsichtbare Parasiten") von Jack Finney, fiel anfangs in der Flut billiger Science-Fiction-Filme der fünfziger Jahre nicht sonderlich auf. Erst einige Jahre später entdeckte die französische Filmpublizistik das Werk und feierte es als einen "Klassiker". Regisseur Don Siegel nannte die Produktion einmal seinen "künstlerischen Höhepunkt", und Peter Bogdanovich urteilte, es handle sich um "den besten und erschreckendsten Science-fiction-Film, der jemals gedreht wurde". Zumindest ist die düstere Fiktion das psychologisch Beklemmendste, was das SF-Kino der Nach-McCarthy-Ära hervorgebracht hat. Im Gegensatz zu den glupschäugigen Monstern des gängigen Gruselfilms der Herstellerfirma Allied Artists handelt es sich hier um einen gestaltlosen Aggressor, eine gesichtslose Macht, die vom Menschen Besitz ergreift, ihn transformiert, verändert, seiner Individualität beraubt, zum Teil einer uniformen Masse macht, für die Emotionen ein Fremdwort sind. Er habe wirklich das Gefühl, dass die meisten Leute solch innerlich leere Hülsen seien, erklärte Siegel die Allegorie: "Sie wachen am Morgen auf, und sie haben einen Arbeitsplatz. Sie frühstücken also, und dann gehen sie zur Arbeit — und kommen heim und essen zu Abend, und dann sehen sie fern und gehen ins Bett. Das ist ihr ganzes Leben. Am nächsten Morgen, wenn sie wieder aufwachen, fängt alles von vorne an. Sie haben keine Träume. Sie können nichts lieben. Sie fühlen überhaupt nichts." Er habe, unterstützt von Wanger, vorgehabt, schreibt Siegel in seiner Autobiographie, die Idee von den Schoten, die die Welt übernehmen, so normal und natürlich wie möglich darzustellen: "Aus diesem Grund ließen wir die verschiedenen Personen in dem Film, wenn sie zum ersten Mal von den Schoten hörten, diesem komischen Gerücht nur wenig oder keinerlei Beachtung schenken. Aber wenn sie dann plötzlich dem monströsen Horror von Angesicht zu Angesicht gegenüberstanden, war ihre Reaktion blankes Entsetzen, wie es im richtigen Leben gewesen wäre."

Wenn das Phantastische nur wirksam sei als die Kraft, die in das normale Leben hereinbreche, schreibt Georg Seeßlen, und ein guter phantastischer Film deshalb davon lebe, dass er zunächst einmal ein sehr präzises Bild der normalen Wirklichkeit gebe, dann entstamme die spezifische Paranoia in Siegels Film dem Umstand, dass das Phantastische nichts weiter sei als die potenzierte Normalität. Dementsprechend konnten Siegel und Wanger aus der Not (ein für Science-fiction eigentlich zu niedriges Budget) eine Tugend machen und sich der semidokumentarisch-schwarzweißen Raffinesse eines Film-noir-Thrillers bedienen. Die Drehorte wurden in Hollywoods Nachbarschaft gefunden. Auf kostspielige Special-effects wurde verzichtet. Die Darsteller, gleichwohl routiniert, gehörten nicht zu den Topverdienern der Branche. All dies trug zum kalkulierten Realismus des Projekts bei. Stilistisch sei der Film männlich und energisch, folgert John Baxter: "Der konsequente Einsatz von Weitwinkelaufnahmen aus niedriger Perspektive öffnet das Bild mit Wolkenformationen, Landschaften, Gebäuden, die weite dunkle Straßen rahmen. Die Sequenzen in der Stadt, on location gefilmt, sind fast alarmierend real. Siegel schickt seine Protagonisten kontinuierlich aus ruhigen, melancholischen two-shots [Einstellungen mit zwei Personen] in helles Areal; die Liebenden, die eine Treppe hinuntergehen und sich in gleißendem Sonnenlicht an der Tür trennen; McCarthy, der Wynter aus einem dunklen Haus zu seinem Wagen bringt, der unter einer Straßenlaterne parkt. Wie in den Filmen von (Jack) Arnold entsteht der Eindruck von Menschen, die sich durch eine irgendwie bedrohliche Landschaft bewegen und deren Leben und Beziehungen nur sicher sind, solange sie das Licht suchen." Invasion of the Body Snatchers, obwohl Produkt des Kalten Krieges, hat eine zeitlose Dimension — mit tragikomischem Anflug. Letzteres freilich war den Verantwortlichen bei Allied Artists zu viel, und sie bestanden auf einem Prolog und einem Epilog. Siegel dazu: "Zögernd willigte ich ein. Im Epilog findet sich Miles im städtischen Hospital wieder, wo er einen ungläubigen Psychiater und einen Krankenhausarzt davon zu überzeugen versucht, dass Schoten die Macht an sich reißen wollen. Da wird ein Notfall eingeliefert. Der Fahrer der Ambulanz behauptet, der Fall habe sich ereignet, als ein Laster voll mit Schoten umgekippt sei. Der Psychiater sieht Miles an und verständigt das FBI." 1977 wurde der Stoff von Philip Kaufman neu verfilmt — mit Donald Sutherland, Leonard Nimoy und Siegel in einer Cameo-Rolle. Rolf Giesen, Reclams elektronisches Filmlexikon

A masterpiece of sci fi cinema, this adaptation of Jack Finney's novel is set in the small town of Santa Mira, where the local shrink is alarmed by the ballooning number of patients who maintain that their nearest and dearest are not quite themselves. In fact, the town is gradually being taken over by 'pod people', alien likenesses of the inhabitants which lack human emotions. (The original title was Sleep No More: the aliens do the swap while the victim is snoozing). Remade in 1978, this version remains a classic, stuffed with subtly integrated subtexts (post war paranoia etc.) for those who like that sort of thing, but thrilling and chilling on any level. The late Sam Peckinpah can be spotted in a cameo role as a meter reader, and look out for one of the most sinister kisses ever filmed. You're next! TimeOut

Invasion of the Body Snatchers, le seul film de science-fiction de Don Siegel et son film préféré, a toujours bénéficié d'une flatteuse réputation qui l'a placé parmi les chefs-d'œuvre du genre durant les années 50. Réputation entièrement méritée, eu égard d'abord à l'originalité et à l'intelligence de son scenano. Choisi par Walter Wanger, l'un des producteurs hollywoodiens les plus novateurs, le feuilleton de Jack Finney, « The Body Snatchers » (autres titres: « Sleep No More » et « I Am a Pod »), a été adapté avec brio par Daniel Mainwaring (alias Geoffrey Homes), scénariste et écrivain de talent qui avait écrit Out of the Past, The Lawless et, pour Don Siegel, The Big Steal et Baby Face Nelson. Au-delà de certaines lacunes dans le détail de l'action, il faut souligner que la force de la progression dramatique et l'aspect humaniste de l'histoire sont les éléments que Mainwaring a surtout développés. Quant à Don Siegel, il a filmé son récit comme un thriller, avec de la vitesse (un tournage sans repentir de 15 jours), du rythme, du réalisme (utilisation systématique des extérieurs réels californiens), de la simplicité (très peu d'effets spéciaux) et beaucoup de tension. L'énergie et l'efficacité de sa mise en scène ont libéré toute la charge d'angoisse latente contenue dans les prémisses du récit et dans le récit lui-même. Mais si le film est resté aussi présent dans les mémoires, c'est surtout à cause de son caractère authentiquement et spontanément allégorique. Sans artifice ni pathos, l'invasion de ces « légumes cosmiques » contient une allégorie saisissante de toute entreprise de déshumanisation, qu'elle se situe à un niveau politique, moral ou tout simplement psychologique. Le message du film est, par nature, anti-totalitaire mais il s'en prend aussi, comme le soulignent les propos de Siegel lui-même, à cette sorte de cancérisation du monde et des individus provoquée par l'indifférence, la disparition de toute réaction émotive, l'absence de passion et de rage à défendre ses idées. En ce sens, Invasion of the Body Snatchers est toujours un film d'actualité. Jacques Lourcelles: Dictionnaire du cinéma, vol. 3: Les films

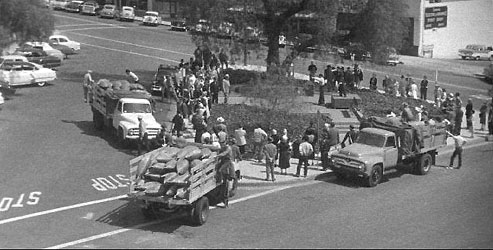

Invasion of the Body Snatchers, troisième produit de la collaboration Siegel-Mainwaring, reste, de très loin, le meilleur film de science-fiction que nous ayons vu, si l'on excepte 2001 : A Space Odyssey de Stanley Kubrick. Les progrès d'un envahisseur invisible y étaient montrés par l'étude de l'évolution psychologique des envahis, qui perdaient progressivement leur personnalité, et il est impossible d'oublier la conclusion à la Richard Matheson, terrifiante malgré un retournement optimiste imposé par le studio. Cela dit, on est parfois gêné, en revoyant le film, par une direction banale presque toujours inférieure aux possibilités du sujet, qu'elle schématise au lieu de l'enrichir, négligeant atmosphère et personnages au profit du seul mouvement, échouant à créer le climat de malaise croissant qui aurait dû conduire le film du quotidien au fantastique. Jean-Pierre Coursodon, Bertrand Tavernier: In seinem Film beschwört Don Siegel den Alptraum des Identitätsverlustes in einer Umgebung, die selber dafür wie prädestiniert erscheint. INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS verzichtet auf aufwendige Trickaufnahmen und Szenen voller Schrecken oder Ekel. Das eigentliche Grauen steigt vielmehr aus der Tatsache auf, daß gerade das Allervertrauteste zum Feindlichen, das Allzubekannte zur Bedrohung wird. Siegel hat on location, in einer wirklichen amerikanischen Kleinstadt gedreht. "Die Stadtszenen, an realen Schauplätzen gedreht, sind fast beunruhigend echt. Siegel schickt seine Personen ständig von ruhigen, schwermütigen Zweier-Bildern in helle Flächen hinaus. Die Liebenden gehen eine Treppe hinab, um sich in einem See von Sonnenlicht an der Tür zu trennen. McCarthy trägt Wynter aus einem dunklen Haus bis dorthin, wo sein Auto unter der Straßenlaterne steht. Wie in Jack Arnolds Filmen ergibt das die Wirkung von Leuten, die sich durch eine verschwommen-bedrohliche Landschaft bewegen, ihr Leben und ihre Beziehungen sind nur so lange ungefährdet, wie sie in der Nähe des Lichtes bleiben" (John Baxter: Science-Fiction in the Cinema. New York 1970.) Die Umgewandelten behaupten, sich in ihrer neuen, seelenlosen Identität viel wohler zu fühlen als vorher. Sie müssen die Welt, die sie vorgefunden haben, gar nicht verändern; sie könnte mit ihnen an der Macht so weiter funktionieren, nur reibungsloser. Wie viele andere Science Fiction-Filme dieser Zeit entwirft auch INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS das Bild einer amerikanischen Gesellschaft, die von Angst geplagt ist. In diesem Film aber wird deutlicher als sonst, daß solche Angst weniger von äußeren Bedrohungen als von einer inneren Entwicklung der eigenen Gesellschaft herrührt. Die Vision einer Welt leerer Menschenhülsen, von "pods" (= Schoten, Hülsen, aber auch Kollaborateure, Mitläufer), ist interpretiert worden als Metapher auf Systeme des politischen Totalitarismus, und man hat Siegels Film in eine Reihe gestellt mit Filmen, die als Produkte des Kalten Krieges Invasionsfurcht und Vernichtungsphantasien beförderten. Eine andere, stringente Deutung läßt INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS aber auch als Parabel auf den militanten Konformismus und'die Gesinnungsschnüffelei der innenpolitischen Situation der fünfziger Jahre erscheinen, in der der McCarthyismus die Herrschaft bis in die alltäglichsten Lebensbedingungen innehatte. Die aktuellen Eindrücke sind am ehesten in der Szene spürbar, wo Miles verzweifelt in die Kamera ruft: "You're Next! " Genau dieses Gefühl aber, jederzeit der nächste sein zu können, der in die Mühlen der antikommunisfischen "Hexenjagd" gerät, war damals verbreitet. Siegel selbst will auf Identitätsverlust in allen möglichen Gesellschaftsformen hinweisen. Der Film bot ihm allerdings auch Gelegenheit, mit Hollywood abzurechnen, wo er das Muster einer durchgeformten "pod society" wähnte. Der Regisseur selbst: "Da gibt es Menschen, die eigentlich nur noch von der äußeren Hülle nach Menschen sind. Leute, die kein Gefühl mehr für Liebe, für Rührung haben, die einfach nur existieren, atmen, schlafen. Davon handelt mein Film. Und diese Hüllen wollen glauben machen, es sei gut, andere Menschen auch in solche Hüllen zu verwandeln; es sei besser, eine seelenlose Hülle zu sein, als ein gebrechlicher Mensch mit Sorgen. Dagegen bedeutet eine solche Hülle nicht zu sein, Herausforderungen zu erwarten, auch das Unglück zu begrüßen und die eigene Existenz zu behaupten. Das Dasein ist so lange überhaupt etwas wert, wie es eine Herausforderung gibt. Ohne sie würde man nicht leben." Die nachträglich von den Produzenten verlangte Rahmenhandlung ist dieser Intention des Regisseurs eher hinderlich und kam nur gegen den Widerstand von Siegel und Drehbuchautor Daniel Mainwaring zustande. Ursprünglich sollte der Film damit enden, daß Miles auf der Straße vergeblich nach Hilfe sucht und schließlich den (mittlerweile fast schon klassischen) Satz in die Kamera ruft: "Ihr seid die nächsten! " Dieser Satz verweist das Geschehen nicht nur gewissermaßen an das Leben des Zuschauers selbst, er ist auch der Höhepunkt in der Spannungsdramaturgie von Siegels Film. Denn darin geht es viel weniger um den Kampf gegen die Eindring-, linge als darum, daß der Held in eine ungeheure persönliche (und metaphorische) Krisensituation gerät, weil er einerseits keinem Menschen mehr trauen kann, und andrerseits nirgends, auch bei den noch nicht "befallenen" Menschen, auf Gehör und Solidarität stößt. Wenn das Phantastische wirksam ist nur als Kraft, die in das normale Leben hereinbricht, und ein guter phantastischer Film deshalb davon lebt, daß er zunächst einmal ein sehr präzises Bild der normalen Wirklichkeit gibt, dann entstammt die spezifische Paranoia an Siegels Film dem Umstand, daß das Phantastische nichts weiter ist als die potenzierte Normalität. Mit der Bewegung des Films entsteht ein Mißtrauen gegenüber allem (scheinbar) Normalen, das wie bei den Pods darin besteht, daß die Gefühle ersetzt werden durch Konventionalität. Siegel zeigt dies sehr nüchtern, ganz ohne die im Genre zu dieser Zeit übliche moralische Diskriminierung des Durchschnittsmenschen. "Erst wenn man darum kämpfen muß, ein Mensch zu bleiben, wird einem klar, was es überhaupt bedeutet, ein Mensch zu sein", sagt der Held einmal. Aber auch er findet kein Mittel gegen die Schotenmenschen. Traditionelle Mittel gegen phantastische Wesen versagen: Er versucht sie zu "pfählen", wie man Vampire erlegt, und er versucht sie zu verbrennen, beides ohne Erfolg. INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS unterläuft also auch Konventionen des Genres; der Film funktioniert als Thriller. Bei seinem ersten Einsatz in des Kinos ging Don Siegels grandioser B-Film in einer Flut von mehr oder minder spektakulären Science Fiction-Filmen unter. Er war mit minimalem Budget in der Drehzeit von 14 Tagen geschaffen worden. In deutschen Kinos lief der Film zunächst unter dem Titel DIE DÄMONISCHEN; auch hier war ihm kein allzu großer Erfolg beschieden. Erst später wurde er von französischen Cinéasten entdeckt und hoch gelobt. Mittlerweile gilt INVASION OF TEE BODY SNATCHERS gar als "Kultfilm" und wird jedenfalls als einer der wichtigsten SF-Filme der fünfziger Jahre eingeschätzt. Peter Bogdanovich hat INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS als "besten und zugleich erschreckendsten Science Fiction-Film, die jemals gedreht wurde" bezeichnet, und auch Siegel selbst, gewiß kein Regisseur der großen Geste, hält den Film für seinen "künstlerischen Höhepunkt". Leslie Halliwell dagegen würdigt, daß bei diesem Film alle Beteiligten "mit Intelligenz und Subtilität zu Werke gegangen seien. Die Ablehnung des Films war möglicherweise nicht immer frei von Furcht gegenüber dem gezeigten Gesellschaftsbild (einen "utopischen Gruselfilm aus kranker Phantasie" nannte der katholische filmdienst INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS). Wie die meisten Filme von Don Siegel hat der Film seine mitreißende Wirkung vor allem durch eine fulminante Montage, die den Zuschauer unweigerlich in den Sog des Geschehens zieht. Diese durch und durch von Action, von "körperlichem" Geschehen bestimmte Montagetechnik, haben im übrigen unabhängig voneinander Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut und Jean-Luc Godard entdeckt, beschrieben und für die eigene Arbeit nutzbar gemacht. Verstörend, bei aller handwerklichen Brillianz, sind viele Filme Siegels, weil sie Muster der jeweiligen Genres geschickt unterlaufen und verändern und oft unverhofft tief in das Seelen- und Sozialleben von Menschen dringen, die in pausenloser Aktion gezeigt werden. Siegel schafft in seinen Filmen Ausnahmesituationen, in denen einzelnen widerfährt, was zugleich ganzen Gesellschaften (genauer: Teilen der amerikanischen Gesellschaft) widerfährt: "All die Schlüsselwörter, die man von Kindheit an lernt, werden vollständig umgekrempelt: Verwandte, Freunde und Geliebte sind nicht gutwillig, Psychiater wollen ihren Patienten nicht helfen, Schlaf ist nicht wiederbelebend, das eigene Haus ist nicht sicher, die Heimatstadt beherbergt feindliche Organismen, die einem die Identität rauben können, Pflanzen sind bösartig und führen ein Eigenleben, Verkehrspolizisten und Parkuhrkontrolleure sind Verbündete des Feindes. Die ganze Welt hat sich wahrhaftig vereint, um einen zu erledigen, um die Seele, die Persönlichkeit und das Bewußtsein zu zerstören." (Judith M. Cass: Don Siegel. New York 1975.) INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS ist (unerreicht auch von dem Remake von 1978) das vollendete Bild der Entfremdung im Gewande eines Science Fiction-Films. Georg Seeßlen, Lexikon des phantastischen Films A classic and highly influential science fiction film which is frightening in spite of the absence of any explicit violence. Successfully remade in 1978 with Donald Sutherland. Like many horror and science fiction films of the 1950s there is a "subtext" which refers to the Cold War and the McCarthy period of anti-communist Congressional investigations. The fear of communist inflitration, communist invasion, and nuclear war is transferred to stories of invasion by aliens from outer-space. The communist "other" becomes literally the "alien." The treatment of nuclear war and invasion can be that of warning, as in "The Day the Earth Stood Still" (1951) with the robot Klaatu urging the scientists of the world to act in unison to overcome the political divisions of the world, or helplessness in "Invaders from Mars" (1953) in which a small boy realises that his parents have been taken over by aliens and there is nothing he can do. Common feature is the single individual who is aware of the danger of society being taken over/corrupted and who takes steps to warn others, but who is ignored. [...] THINGS TO NOTE 1. The absence of violence in the film. We witness no deaths and the "monsters" seem to be harmless plants, which we see only briefly. (Compare with the "pods" in Ridley Scott's film "Alien" (1979) and the violent and bloody manner in which they take over humans and in turn are destroyed by the Colonial Marines). The film critic Leslie Halliwell, whose views I seldom share, correctly calls this film "the most subtle film in the science-fiction genre cycle, with no visual horror whatsoever." 2. The apparent "normalcy" of the town and the inhabitants after they have been replaced by their pod duplicates. The "invasion" seems to be a non-violent one and the people seem to welcome the change that has come over them, as a solution to long-felt problems. One reading of the film is that the pods are like the spread of socialist/communist ideas — affecting ordinary everyday Americans, with little or no outward change in their behaviour, but which changes their whole way of thinking about the world. Reference to the "brainwashing" of US POWs in Korea by communist Chinese captors. Of the 7,000 captures, none escaped, few made any attempt and 70% collaborated with the captors. 3. The indestructibility of the pods. At various times they are burnt and even subjected to a ritualistic vampire "killing" with a pitchfork driven like a stake through the heart. Is this the way to drive out "godless" communism? DS seems to be suggesting through the indestructibility of the pods that the invasion will succeed. 4. The fruitless warnings which are given but not heeded by others. The patients who come to the doctor, the symbol of authority in the town, to warn him of what is happening. He is away and then, when he returns, slow to act. The saddest and most horrible example of unheeded warning is the frightened boy, Jimmy Grimaldi, who is stopped by MB running away from his (pod) mother. He cannot convince the doctor that his mother has become a monster and is handed back to her to face certain "death." MB also faces this problem, at the beginning of the film and again at the end. Can this be seen as an indirect justification of the McCarthy trials, as a warning against "invasion" of American institutions by communists? Compare with warnings by Gen. Jack D. Ripper of communist plot to flouridate the water in Kubrick's "Dr Strangelove." Compare handing over POWs and other Soviet "nationals" to Stalin after WW2 to face camps or execution. 5. The pschychiatrist Kaufmann's diagnosis that the town is suffering from an epidemic of mass hysteria brought on by worrying about what is going on in the world (i.e. Cold War). MB describes it as a malignant disease spreading through the entire country, evil taking possession of the town. It is the result of atomic radiation — "anything is possible after the events of the past few years" (atomic testing). 6. MB's solution is to go 'the authorities" (the FBI). Compare faith in authorites in "The Atomic Cafe". 7. The feeling of helplessness we share with MB when he runs onto the highway and is surrounded by speeding cars (a symbol of capitalist individualism) unwilling to stop to listen to his warnings. His sense of doom increases when he sees the trucks with cities of destination on their sides distributing the pods across the US. 8. The changes which are supposed to be brought about by the takeover of individuals by their pod duplicates. One pod person promises they will be "reborn into an untroubled world where everyone is the same." They give up much of their individuality and behave like a mob (like ants in a nest or bees in a swarm, mob chases MB and Becky into cave), they reject the main institutions of capitalist America (the nuclear family, monogomy, small business — Mr Grimaldi, private property), they stop going to the country club (commies don't like having fun? don't drink cocktails, martinis?), they agree to sacrifice themselves to the common good, they engange in onerous "party" activity organised by "party officials" (i.e. the loading of trucks to distribute the pods across America), and they are generally submissive and compliant. In other words they have become "communists". 9. The psychiatrist (or rather his duplicate) explains: out of the sky came a solution, you will be born into a world where everyone is the same, no need for love or emotion or feelings, ony the instint to survive remains, we are better off without love, desire, ambition and faith, and ultimatley you have no choice. 10. The logical contradition at the end of the film concerning Becky Driscoll's pod duplicate. Stuart Samuels: The Age of Conspiracy and Continuity: Director Don Siegel about his film "We spent very little on special effects, less than 15,000 dollars, with which our production designer, Ted Haworth, worked miracles. We concentrated on the story and the acting, instead of spending thousands on special effects and sticking wooden actors on the screen. This is probably my best film because I hide behind a facade of bad scripts, telling stories of no import and I felt that this was a very important story. I think that the world is populated by pods and I wanted to show them. I think so many people have no feeling about cultural things, no feeling of pain, of sorrow. I wanted to get it over and I didn't know of a better way to get it over than in this particular film. I thought I shot it very imaginatively. And I was encouraged all the time by Wanger. The film was nearly ruined by those in charge at Allied Artists who added a preface and ending that I don't like. The political reference to Senator McCarthy and totalitarianism was inescapable but I tried not to emphasise it because I feel that motion pictures are primarily to entertain and I did not want to preach." Alan Lovell: Don Siegel. American Cinema. London 1975, S. 54 "Santa Mira: The picture begins with Dr Miles Bennell arriving in the small town of Santa Mira, a suburb of Los Angeles, by train. The name of the town we used is Sierra Madre, which we picked because it fit the story and worked out very well. We shot in the city and its environs for about a week. We also used Bronson Canyon, with its tunnels, in the Hollywood Hills.(...) Auftritt Sam Peckinpah: (Miles and Becky) lean against the wall of the tunnel, Miles unable to take another step. He sets Becky on her feet. (...) The Silhouette of a man (Sam Peckinpah) approaches the tunnel's entrance. He shouts back to the crowd that they could be inside, and his cry echoes and re-echoes throughout the tunnel. Keine Tricks: No second unit was used here, or anywhere else in the picture. There was no process in the picture: every shot was authentic. The shots of Kevin's final scene were filmed just before dawn, and Kevin was in real danger, considering that he was at the breaking point of complete exhaustion. Normalität: My idea, which Wanger seconded strongly, was to confront the idea of pods taking over the word als normally and naturally as possible (...) We therefore had the various characters in the picture, when first learning about the pods, pay little or no attention to this silly rumour. But when they were suddenly face to face with the monstrous horror, their reaction was startlingly frightening, as it would be in real life. Humor: Allied Artist, bursting at the seams with pods, took Wanger's and my final cut and edited out all the humour. In their hallowed words, 'Horror films are horror films and there's no room for humour. Rahmenerzählung: The studio also insisted on a prologue and an epilogue. Wanger was very much against this, as was I. however, he begged me to shoot it to protect the film, and I reluctantly consented (...). Oddly enough, in Europe and in the 'underground' in America, Invasion of the Body Snatchers was shown with the prologue and the epilogue edited out. Like this, it was known as 'the Siegel version'." Don Siegel: A Siegel Film. An Autobiography. London 1993 S. 178-185 Frage: Wie war es möglich, unter den Augen der strengen McCarthy-Doktrin eine so durchsichtige Parabel auf den McCarthyismus durchzusetzen? Siegel: Sie sehen das zu problematisch. Sicher, die Geschichte von den pflanzlichen Lebewesen, die die Welt erobern und als seelenlose Kopien friedlicher Bürger Böses verbreiten, kann verständlich machen, was ich gemeint habe. Doch die Studiobosse sind im Grunde sehr naiv, und dieser Mister Siegel war 1956 für die Amerikaner ein völlig unbeschriebenes Blatt — etwa wie heute Stephen King, ein Mann des Trivialen, der Fantasy, der Fiction. Denkt man da an die Kommunistenjäger McCarthy, Nixon oder Reagan? Nein, man denkt an Action- und Horror-Fiction und einen Mann, der damit Geld verdient. Interview mit Heiko R. Blum. epd Film 6/1991. S. 23

"Pod people” became a chilling metaphor for the Cold War in sci-fi’s ultimate paean to paranoia, Invasion of the Body Snatchers. For almost half a century following the end of World War II, America was wracked with fears of atomic annihilation by one or more of its former allies. Families took out mortgages to have nuclear bomb shelters built in their back yards. Grandstanding politicians ran amok "rooting out Communists” and succeeded mainly in ruining many lives, including their own. Adding to this atmosphere of abject suspicion were the ubiquitous reports of unidentified flying objects. Little wonder, then, that moviegoers of the 1950s were engulfed by yarns about invaders from other nations and other planets. From an avalanche of awful, fast-buck productions on this subject, there emerged a handful of jewels during 1951-53, notably The Thing, The Day the Earth Stood Still, War of the Worlds, Invaders from Mars, and It Came from Outer Space. Another first-rate film sprouted up, belatedly, in 1956: Invasion of the Body Snatchers. With a final cost of $416,911, this didn’t really qualify as a "big” picture; either the "ambitious B” or "nervous A” category would have been appropriate. Comprising the cast were several excellent, stage-trained actors whose names, unfortunately, meant little in terms of box-office draw. The picture’s chances for choice playdates were nil because it belonged to a genre that had fallen into disrepute, and also bore the brand of Allied Artists, which exhibitors remembered by its former name, Monogram, a studio that had specialized in low-budget productions. Allied was now producing the occasional prestige picture, along with low-budget items such as the Bowery Boys and Bomba the Jungle Boy series. On the other hand, the producer of Body Snatchers was Walter Wanger, a top-of-the-line veteran who at the time was a trifle tarnished and battle-scarred. Famed for the likes of Queen Christina, The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, Algiers, Stagecoach, Foreign Correspondent, Canyon Passage and Scarlet Street, Wanger landed at Allied after a disastrous fall from power. Between 1932 and 1948, he had produced 51 major features for MGM, Columbia, Paramount, Universal and United Artists. However, he then formed an independent company to make an epic production of Joan of Arc starring Ingrid Bergman. This film cost $4,650,506 and went in the red to the tune of $2,480,436. Refusing to seek bankruptcy protection, he made two good pictures for Eagle Lion and another for Columbia in 1948-49, but lost heavily on all three. Wanger then languished among the unemployed until June of 1951, when his friends at Monogram Pictures, Walter and Harold Mirisch and Steve Broidy, offered him a producer’s berth. Monogram had survived many years on Poverty Row. At $12,500 and 14 percent of net profits per picture, Wanger’s contract was a far cry from the cushy deals he had enjoyed during his days at the majors. He restored his reputation in 1954, at the newly renamed Allied Artists, by producing the hit picture Riot in Cell Block 11 for just $298,780. The success of Riot was a shot of financial adrenalin for Wanger, Allied and director Don Siegel. Wanger and Siegel would soon team up again. Jack Finney’s novel The Body Snatchers had been serialized in Collier’s magazine in November and December of 1954. Wanger submitted it as a film project to the AA management, along with five other properties, and AA bought the screen rights immediately. Impressed by Siegel’s no-nonsense yet expressive directorial style, Wanger was anxious for him to direct the picture. Siegel signed on to tune of $21,688. When Riot scribe Richard Collins proved unavailable, Siegel suggested Daniel Mainwaring, with whom the director had collaborated on three prior films. Mainwaring, a popular novelist under both his own name and the pseudonym Geoffrey Homes, wrote the script in close consultation with Siegel. Collins later worked on several scenes after principal photography had commenced. [...] Mainwaring’s skill at mastering dialogue was most conspicuously illustrated in his story and script for RKO’s great 1947 film noir, Out of the Past. He and Collins brought a definite noir quality to Body Snatchers, as well as plenty of crackling talk. They let the converted Dr. Kaufman explain the hideous situation in a bone-chillingly bland manner: "Think of the marvelous thing that has happened. Seeds drifting through space for years, ... took root by chance in a farmer’s field, to offer us an untroubled world ... There’s no need for love.” Miles responds, "No emotions? Then you have no feelings, only the instinct to survive? You can’t love or be loved, right?” Kaufman explains patiently, "You say it as if it were terrible. Believe me, it isn’t. You’ve been in love before. It didn’t last. It never does. Love, desire, ambition, faith – without them life’s so simple, believe me.”

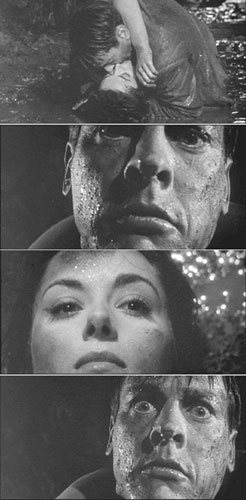

Ellsworth Fredericks, ASC was assigned to photograph Body Snatchers. He had started as assistant cameraman to John Seitz, ASC in 1927, and was dividing his time between making TV dramas for MCA and features at Allied Artists, for whom he photographed 13 pictures in four years. Art director Ted Haworth, who had designed Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train and I Confess, began busily scouting locations on the first week of January, 1955. To represent the fictitious Santa Mira, he first considered Mill Valley (located to the north of San Francisco) which had been Finney’s model for the doomed town. He and Siegel decided on Sierra Madre, a beautiful, hill-laden San Gabriel Valley town just north of Pasadena. Principal photography commenced on March 23, with five days of exteriors in Sierra Madre. A few other location shots were captured in the Los Angeles area, after which interiors were shot at the studio. On April 7, the film’s long climactic chase, which had begun in Sierra Madre, was continued on Mulholland Drive — a thoroughfare which snakes over the Santa Monica Mountains from Hollywood to the Pacific — and in the granite crags and caves of Brush Quarry in Bronson Canyon, a part of the parks administration in Hollywood. Brush Quarry — as it had in hundreds of serials, Westerns and horror films — provided ominous shapes that added to the film’s suspense and terror. Cold fear mounts after the couple takes refuge in the dark mine tunnel. Lying in a muddy depression under some boards, they listen to the approach of the pod people and glimpse their running feet and flashlight beams through the spaces between the boards. The sound effects are as harrowing as the visuals. The climactic night scenes of Miles’ hysterical attempts to stop traffic on the freeway were actually filmed before dawn on a little crossing bridge, utilizing about 50 vehicles driven by professional stunt drivers. Although McCarthy teetered dangerously close to fatigue, the actor performed the hazardous sequence without a double. Before even a frame of film had been shot, the filmmakers decided to minimize the use of special effects, avoiding process screens and opticals in favor of both realism and economy. The only exceptions to the rule were full-scale seed pods and embryo bodies, which cost about $30,000 overall. Ted Hayworth designed ten rubber pods for the transformation scenes, while many non-functioning ones were crafted from plastic. It was also necessary to make latex replicas of the nude bodies of McCarthy, Wynter, Jones and Donovan to be revealed (but also tastefully concealed) in a welter of froth and bubbles when the pods burst open. After a studio executive called Siegel to his office and informed him that nudity would never besmirch an Allied Artists picture, the director had the body casts made in secret. Siegel openly quipped that the executive himself had become a pod. Milt Rice described the making of the pods when the effects were submitted for Academy Award consideration: "The construction began with the sculpturing of full-sized clay models. From these models, casts were made and form molds taken. Liquid latex was used to make the ‘skins’ of the pods, and these skins were, in turn, mounted on mechanized frames. In addition, life-sized replicas of the four principals and ‘embryo blanks’ were also constructed in the above manner. "During actual operation, hydraulics were used to manipulate the action of the pods,” he added. "Compressed air and chemicals were employed to cause the pods to pulsate and emit frothy substances, as well as [to force] the embryos from the pods. Substitution of life-sized replicas of principals was handled manually.” The "birth” scenes were overcranked so that the bubbles appeared to burst ponderously; the footage was then printed in reverse so that the bubbles seemed to be flattening onto the skins of the embryos. The "unfinished” blank look of the pale embryos is not gruesome, but subtly horrifying.

The picture’s principal shoot wrapped on April 18, after 10 days of rehearsal and 19 days of photography. Postproduction would prove to be much more time-consuming. For a month, Siegel toiled with the studio editorial supervisor, Richard Heermance, to create a rough cut. Studio chiefs already had demanded the deletion of several humor-tinged scenes that Siegel and Mainwaring believed to be vital to the story’s overall realism. Wanger complained in general about the "sharp, so-called ‘B’ cutting.” He also had McCarthy, who was then in New York, record the opening narration from Finney’s book and dub some dialogue. Fredericks’ photographic touches greatly enhance the story. The early town scenes, presented with long takes, bright daylight and eye-level camera angles reminiscent of the Blondie and Hardy Family series films, evoke realistic normality. Miles is sometimes shown from a slight low angle to emphasize his strength and dependability. When the pods are discovered, the filmmakers employ a few "Dutch angles” and sharp tilts. As the nefarious alien plot is revealed, the shadows become darker and viewers are treated to some deep-focus shots in the best Citizen Kane tradition. This tactic is particularly chilling when the pods are shown with the humans they will replace; in one shot, Jack’s pod double awakens on a pool table in the foreground as Jack sleeps at a bar behind it. The climactic high-contrast scenes of flashlights and hulking silhouettes in the dark cave, including pit-shots of the pod-people thundering over the lovers’ hiding place, could hardly be better. Wanger was horrified to learn that the Allied execs opted to release the picture in SuperScope, an anamorphic widescreen process introduced by RKO Radio in 1954. It differed from CinemaScope in that the photography was done with normal lenses; the images were squeezed at the printing stage rather than in the camera. Wanger argued that a duped image would not do justice to Dana Wynter’s beauty, that the carefully wrought compositions would be ruined, and that the widescreen effect would make the picture resemble recent inferior anamorphic sci-fi pictures Again, he was overruled – widescreen was considered a "must” at the time due to the perceived competition with television for audiences. Incidentally, Wanger was dead right on all counts. The damage caused by this last-minute decision can hardly be exaggerated. Fredericks had composed the picture for the 1.33:1 ratio, and the image-chopping required to obtain the 2:1 ratio needed for SuperScope not only destroyed the compositions, but left important details out of the frame. In addition, the images became grainier when the remaining frame was blown up to fill the wide screens. Only a very good movie could survive such butchery; somehow, Body Snatchers did. The makers of the film wanted a high-class title for the film. McCarthy suggested Sleep No More, while Siegel came up with Better Off Dead. The studio, wanting something more sensational, submitted They Came from Another World. The final choice of the executives was a compromise, combining a typical sci-fi title with novelist Jack Finney’s original.

Siegel filmed these segments over four days in September, objecting the entire time because he felt that they compromised the power of the original ending. "Allied Artists,” he wrote many years later, "was bursting at the seams with pods.” Many agree with him, and the picture is sometimes shown in a "director’s cut” with the framing devices removed. On the other hand, many of the preceding sci-fi-horror films of the period also end with epilogues informing us that the crisis will continue. An apparently happy ending would cut to, say, an egg hatching or some object hurtling through space on its way to Earth. Then, predictably, a giant question mark would be added to the end title, or "The End” would be replaced with "The Beginning.” It had become a well-worn cliché, and this writer ventures the pod-ish minority opinion that the framing story benefits the film. Upon its release, Invasion of the Body Snatchers attracted little attention. The trade papers, which try to review everything, were enthusiastic, but most mainstream critics pointedly ignored it. Attempts to get the film a Broadway opening failed, and it opened instead in Brooklyn. Wanger made a personal plea to Bosley Crowther, film pundit of the New York Times, to view the film but the critic couldn’t be bothered. Somehow, the picture logged a whopping domestic gross of $1,200,000. As the years passed, it gradually became recognized as the distinctive movie that it is, even to the extent of being remade twice: Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), directed by Philip Kaufman and photographed by Michael Chapman, ASC, transposes the small-town paranoia into the liberal environs of San Francisco while Body Snatchers (1992), directed by Abel Ferrara with cinematography by Bojan Bazelli, transplanted the alien-fueled apprehension to a southern military base. As a home video feature, the original film has enjoyed a long life in black-and-white and colorized versions, and has even been restored for theatrical showings. Many writers and educators have read all sorts of significances into the picture, variously saying it is anti-Communist, pro-Communist, anti-McCarthyist, anti-establishment, and so on and so forth. Wanger, Siegel and Mainwaring all denied such theories, saying that they were only trying to create some popular entertainment. Finney likewise stated that he had no such agendas. After adding Body Snatchers to his resume’, Don Siegel’s career skyrocketed, and he went on to direct a slew of top-drawer action pictures, including The Killers, Madigan, The Beguiled and Dirty Harry. The ingenuity and imagination that Ellsworth Fredericks brought to Body Snatchers marked a turning point in his career. Before his retirement in 1969, he lent his eye to a number of major productions, including Friendly Persuasion, Trooper Hook, The Light in the Forest and Sayonara (for which he received an Academy nomination). After producing the inconsequential Navy Wife for AA, Wanger returned to independent production in 1958 with the highly successful I Want to Live!. Unfortunately, he next assumed the reins of 20th Century Fox’s disastrous Cleopatra, a debacle from which his career never recovered. He was enthusiastically planning new projects at the time of his death in November of 1968.  |

|||||

DVD

Video: Artisan's treatment of this classic on DVD is great. The film looks wonderfully crisp, and the black-and-white picture's contrast looks beautiful. It's a 2-sided disc with the 2.35:1 widescreen version on one side and the full-screen, pan-and-scan version on the other. The print they used for the transfer is a little the worse for wear, with a lot of scratches and pockmarks, but they're only noticeable in a few moments, and not for very long. Otherwise everything looks great. 7 out of 10 Audio: As with a lot of movies from the 50s, the music tends to overpower the dialogue at times, but that's more likely the fault of the original film than of the DVD. At any rate it's in Dolby Digital mono, which is fitting. It would have been silly to remix the audio here, which is pretty dated to start with. 5 out of 10 Extras: The Invasion of the Body Snatchers DVD also features an interviewer with star Kevin McCarthy (done, by the look of it, about 10 years ago — not specifically for this package) and the original theatrical trailer, which is just like you would expect the 1955 trailer for Invasion of the Body Snatchers to be. I would have liked to see the trailer for the 1978 remake of this film to have been included just for giggles. That's it, though — not much to go on. I don't know what else they could have included, but perhaps an essay on the movie or a featurette about its influence on the genre (which was considerable) would have been good. 3 out of 10 Alex Castle, dvd.ign.com |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)

Don Siegel's classic exercise in psychological science fiction has often been interpreted as a cautionary fable about the blacklisting hysteria of the McCarthy era. It can be read as a political metaphor or enjoyed as a fine low-budget suspense movie, and it works well either way. Kevin McCarthy stars as Miles Bennel, a doctor in the small California community of Santa Mira, where several patients begin reporting that their loved ones don't seem to be themselves lately. They look the same but seem cold, emotionally distant, and somehow unfamiliar. The longer Miles looks into these reports, the more stock he places in them, and in time he makes a shocking discovery: aliens from another world are taking over Santa Mira, one citizen at a time. Emissaries from a distant planet have sent massive seed pods containing creatures that can assume the exact physical likeness of anyone they choose. When Santa Mirans go to sleep, the pod creatures take on the shape of their victims and then destroy their bodies. The aliens may look the same, but they possess no human emotions and, like plants, are concerned only with propagating themselves and eventually subsuming the earth. Needless to say, Miles and his friends are terrified, but since it's hard to tell who's a person and who's a pod, they're at a loss for what to do, especially when it seems that there are increasingly more aliens than humans. Invasion of the Body Snatchers builds tension slowly and steadily, dealing not in the shock of bug-eyed monsters common to other 1950s science-fiction movies but in the unnerving possibility that the enemy is among us — and impossible to tell from our allies. The ultra-paranoid conclusion of Siegel's original cut was softened by Allied Artists, who added a framing device that suggested help was on the way. This coda was as effective in blunting the film's grim conclusion as giving a Band-Aid to a beheading victim; few films of the era make it more painfully clear that for these people (and maybe for ourselves), there's no turning back and no way home. Keep an eye peeled for a bit part by soon-to-be-legendary Western director Sam Peckinpah, who plays a meter reader and also (uncredited) helped write the screenplay. Based on a novel by Jack Finney, Invasion of the Body Snatchers was remade in 1978 by Philip Kaufman and in 1993 by Abel Ferrara (as Body Snatchers); and its influence can be felt from The Stepford Wives (1975) to The X-Files.

Don Siegel's classic exercise in psychological science fiction has often been interpreted as a cautionary fable about the blacklisting hysteria of the McCarthy era. It can be read as a political metaphor or enjoyed as a fine low-budget suspense movie, and it works well either way. Kevin McCarthy stars as Miles Bennel, a doctor in the small California community of Santa Mira, where several patients begin reporting that their loved ones don't seem to be themselves lately. They look the same but seem cold, emotionally distant, and somehow unfamiliar. The longer Miles looks into these reports, the more stock he places in them, and in time he makes a shocking discovery: aliens from another world are taking over Santa Mira, one citizen at a time. Emissaries from a distant planet have sent massive seed pods containing creatures that can assume the exact physical likeness of anyone they choose. When Santa Mirans go to sleep, the pod creatures take on the shape of their victims and then destroy their bodies. The aliens may look the same, but they possess no human emotions and, like plants, are concerned only with propagating themselves and eventually subsuming the earth. Needless to say, Miles and his friends are terrified, but since it's hard to tell who's a person and who's a pod, they're at a loss for what to do, especially when it seems that there are increasingly more aliens than humans. Invasion of the Body Snatchers builds tension slowly and steadily, dealing not in the shock of bug-eyed monsters common to other 1950s science-fiction movies but in the unnerving possibility that the enemy is among us — and impossible to tell from our allies. The ultra-paranoid conclusion of Siegel's original cut was softened by Allied Artists, who added a framing device that suggested help was on the way. This coda was as effective in blunting the film's grim conclusion as giving a Band-Aid to a beheading victim; few films of the era make it more painfully clear that for these people (and maybe for ourselves), there's no turning back and no way home. Keep an eye peeled for a bit part by soon-to-be-legendary Western director Sam Peckinpah, who plays a meter reader and also (uncredited) helped write the screenplay. Based on a novel by Jack Finney, Invasion of the Body Snatchers was remade in 1978 by Philip Kaufman and in 1993 by Abel Ferrara (as Body Snatchers); and its influence can be felt from The Stepford Wives (1975) to The X-Files.

Wanger wanted to add a prologue and epilogue that emphasized the reality of the film, and linked it to actual struggles with totalitarianism in America and abroad. He thought of opening with a quotation from Winston Churchill, but was refused permission. His attempts to get Orson Welles to do the prologue failed as well. The producer’s next notion was to feature a famous news analyst interviewing Miles in his hospital bed as an opening lead-in. After unsuccessfully approaching several noted broadcast journalists — Edward R. Murrow, Lowell Thomas, Quentin Reynolds, and John Cameron Swayze — he gave up on the idea. Studio executives agreed with Wanger about the necessity of a framing prologue and epilogue, and brought Mainwaring back to write them. The prologue shows a police car bringing Mark, disheveled and half-crazed, to a hospital where he tries in vain to convince both a psychiatrist (Whit Bissel) and a doctor (Richard Deacon) that seed pods are taking over the planet. In the epilogue, an ambulance brings an emergency case to the hospital. After the driver explains that the man was injured in a crash with a truck loaded with huge seed pods, the psychiatrist places a call to the FBI.

Wanger wanted to add a prologue and epilogue that emphasized the reality of the film, and linked it to actual struggles with totalitarianism in America and abroad. He thought of opening with a quotation from Winston Churchill, but was refused permission. His attempts to get Orson Welles to do the prologue failed as well. The producer’s next notion was to feature a famous news analyst interviewing Miles in his hospital bed as an opening lead-in. After unsuccessfully approaching several noted broadcast journalists — Edward R. Murrow, Lowell Thomas, Quentin Reynolds, and John Cameron Swayze — he gave up on the idea. Studio executives agreed with Wanger about the necessity of a framing prologue and epilogue, and brought Mainwaring back to write them. The prologue shows a police car bringing Mark, disheveled and half-crazed, to a hospital where he tries in vain to convince both a psychiatrist (Whit Bissel) and a doctor (Richard Deacon) that seed pods are taking over the planet. In the epilogue, an ambulance brings an emergency case to the hospital. After the driver explains that the man was injured in a crash with a truck loaded with huge seed pods, the psychiatrist places a call to the FBI.