|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

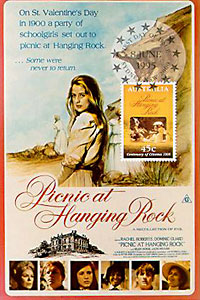

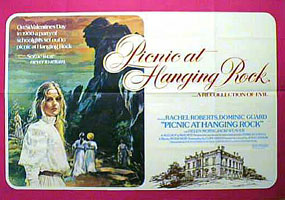

Picnic at Hanging Rock

(Picknick am Valentinstag | Pique-nique à Hanging Rock)

|

|

|

| |

|

Australia 1975 | 115 min – 107 min (Director's Cut)

Regie: Peter Weir

Producer: James McElroy, Hal McElroy

Executive Producer: Patricia Lovell, John Graves

Production Company: Australian Film Commission / BEF Film Distributors Pty. Ltd. / McElroy & McElroy/ Picnic Productions Pty Ltd / South Australian Film Corporation

Screenplay: Cliff Green (after the novel by Joan Lindsay)

Cinematographer: Russell Boyd, A.C.S.; Assistent: John Seale (Eastmancolor, 1.66:1 WideScreen 35mm)

Editor: Max Lemon

Music Score: Bruce Smeaton; Gheorghe Zamfir (musician: pan flute), Ludwig van Beethoven (from "5th piano concert"), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (from "Eine kleine Nachtmusik")

Sound: Don Connolly (recordist) (Mono)

Art Director: David Copping

Costumes: Judith Dorsman

Shooting Location: South Australian Film Corporation Studios / Hanging Rock, Woodend, Victoria / Martindale Hall, Mintaro, South Australia / Strathalbyn, South Australia

Cast: Rachel Roberts (Mrs. Appleyard), Dominic Guard (Michael Fitzhubert), Helen Morse (Mlle. Dianne de Portiers), Vivean Gray (Miss McCraw), Anne Lambert (Miranda), Kirsty Child (Miss Lumley), Tony Llewellyn-Jones (Tom), Jacki Weaver (Minnie), Frank Gunnell (Mr. Whitehead), Karen Robson (Irma)

Premiere: November 1975 • 24 July 1977 (West Germany TV ARD) • 2 February 1979 (USA)

Awards: Best Cinematography Russell Boyd 1976 British Academy Awards • Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, USA 1979 Saturn Award Best Cinematography • British Society of Cinematographers 1976 Nominated Best Cinematography Award

The Director's Cut released in 1998 is 7 minutes shorter than the original version

|

|

|

International Movie Database International Movie Database |

All-Movie Guide All-Movie Guide |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Long before The Truman Show, long before Dead Poet's Society, long before Witness, director Peter Weir created several atmospheric movies in his native Australia, including Picnic at Hanging Rock, arguably his best movie.

Peter Weir is an expert at using the camera to create atmosphere. In movies as disparate as The Truman Show, Fearless, and Witness, Weir has created a palpable sense of longing. All of these movies are about surviving in an environment where the rules of life have been completely changed—through physical constraints, psychological boundaries, and cultural perceptions (respectively). And Picnic at Hanging Rock is no different: it gives us a palpably dense, dream-like atmosphere that forever is on the verge of intoxicating the viewers, as is does the lead characters, in an overpowering aura of longing and repression. With soft-focus lenses, Weir takes us into a world of golden glows and gentle whispers, where the characters exist as hazy, evocative recollections.

Based on a book by Joan Lindsay, Picnic at Hanging Rock takes us to a girls' finishing school in Australia, where the teenage girls embark on a field trip/picnic to a local landmark—a near-vertical precipice called Hanging Rock. While the girls rest at the foot of the rock, a group of four girls begins to traverse the rock. However, something unexplained happens and three of the girls fail to return. And soon afterwards one of their teachers follows and she also disappears. Search parties scour the vicinity of the rock but no traces of the three girls and their teacher are found.

Weir doesn't provide any worldly explanations for the disappearances. Whereas many filmmakers would have provided their own theories, Weir allows the mystery to stand. Instead, he focuses on how everyone else reacts to the disappearances—how the headmistress (portrayed by Rachel Roberts) becomes powerless as her school's reputation is tarnished and parents withdraw their students; how a local boy becomes obsessed with searching for the girls; how an orphan girl named Sara reacts to the disappearance of Miranda, whom she loved. Possible explanations abound—with leading culprits ranging from kidnappers/murderers to UFO abductions—but Weir only provides tantalizing hints.

However, while the movie doesn't provide a definitive physical explanation for the disappearances, Weir loads the movie with clues that the disappearances should be viewed as metaphorical. For starters, the main events take place on Saint Valentine's Day—the most romantic day of the year. However, the teenage girls are trapped at a girls-only school named Appleyard College (an orchard for ripening fruit?). As a result, they pass Valentine's cards among themselves and breathlessly read love poems to each other. In a key scene, Weir shows as they help each other dress, and his camera focuses on a daisy-chain of girls tightening each other's corset. In this land of sexual repression and misplaced sexual yearnings, the girls venture to a towering 500-foot tall rock (with phallic implications?) and four girls in the party begin to climb higher and higher up the slopes. Not surprisingly one girl turns around and runs screaming down the rock. But the others take off their shoes (a sign that they are breaking from sexual repression?), and as the camera idealizes them in a golden haze, they begin their final slow-motion ascent.

On a metaphorical level, the movie suggests that the girls' minds have become foggy (enraptured?) by the rock's magnetic pull (a sign of sexual yearning?) and they have embarked on a hypnotic journey to a mythical never-never land of higher (sexual?) fulfillment. In fact, the pocketwatches of several party members stop dead in the presence of the rock. Of course, the time lapse also begs for a paranormal explanation, as in a UFO abduction or a space/time wrinkle. However, these are needlessly clumsy and blatant explanations for such an ethereal and yet portentous event, especially so in a movie where the atmosphere holds such a palpable and steadfast hold on its viewers. foggy (enraptured?) by the rock's magnetic pull (a sign of sexual yearning?) and they have embarked on a hypnotic journey to a mythical never-never land of higher (sexual?) fulfillment. In fact, the pocketwatches of several party members stop dead in the presence of the rock. Of course, the time lapse also begs for a paranormal explanation, as in a UFO abduction or a space/time wrinkle. However, these are needlessly clumsy and blatant explanations for such an ethereal and yet portentous event, especially so in a movie where the atmosphere holds such a palpable and steadfast hold on its viewers.

Many critics have mistakenly assumed that the events portrayed in Picnic at Hanging Rock are based on actual events that took place in 1900 near Woodend in the state of Victoria. However, as indicated in her book The Murders at Hanging Rock (1980), author Yvonne Rousseau points out that the college didn't exist in 1900 and newspaper records do not mention any disappearances. However, Joan Lindsay's novel, Picnic at Hanging Rock, quotes police transcripts and newspaper accounts like an authentic historical document. This semblance of reality forces us to approach the events seriously. While Weir and cinematographer Russell Boyd's images hold us spellbound, the plausibility of the events intrigues us like an intricate jigsaw puzzle.

When the movie was made in 1975, Weir was not permitted to supervise the final cut. This "Director's Cut" version, available for the first time, restores director Weir's original vision.

Peter Weir, aus europäischer Sicht lange Jahre so etwas wie die australische Ein-Mann-Filmindustrie, eine Fehleinschätzung, die erst in den achtziger Jahren revidiert werden konnte, mutet mit seiner "gothic novel" Picnic at Hanging Rock dem Zuschauer einiges zu. Nicht weil die erzählte Geschichte zu grausig wäre, das Gegenteil ist der Fall, die Inszenierung ist sehr stilvoll und zurückhaltend. Nein, die Zumutung liegt darin, dass er ein Rätsel vorgibt, dem Zuschauer jedoch dessen Auflösung verweigert. Er inszeniert das Nicht-Nachvollziehbare als einen Teil der Wirklichkeit, den man zu akzeptieren hat. Dabei transzendiert auch die kleinste Handlung zu einem Akt mit symbolischer Bedeutung, die weit über den eigentlichen Vorgang hinausweist. Dies wird besonders augenfällig an vielen Elementen, die auf ihren sexuellen Symbolgehalt hin gelesen werden wollen, und an dem harten Kontrast, mit dem ein morbides viktorianisches Erziehungsideal der Überlebenskraft der Natur gegenübergestellt wird. In der Schule herrschen dunkle, meist braune Farbtöne vor, während in der Freiheit der Natur die ganze Farbpalette zu ihrem Recht kommt. Der strengen Symmetrie des kritisierten Erziehungssystems wird Wildwuchs in jeder Form gegenübergestellt. Das reicht von den schwärmerisch eingerichteten Jungmädchenzimmern der Elevinnen bis hin zum Busch und den Felsenformationen des Hanging Rock. Die dem Alkohol ergebene Schulleiterin ist das Sinnbild einer verrotteten Gesellschaft, deren einziger Zweck es ist, ihre Macht zu erhalten, alle vorgeschobenen Gründe sind nichts weiter als Lippenbekenntnisse.

Meisterlich versteht Weir es, in seine Geschichte den roten Faden verdrängter, noch nicht entdeckter, noch nicht gelebter Sexualität einzuweben. Fast scheint es, als müssten die jungen Frauen — ihre schwärmerische Wortführerin wird mit einem Botticelli-Engel verglichen — spurlos aus ihrem sozialen Umfeld verschwinden und sich in die zwar bedrohliche, letztlich aber lebensbejahende Natur hinein auflösen, um endlich Erfüllung zu finden. Zu weit haben sie sich bereits vom Wege entfernt, haben sich in enge Schluchten gezwängt, als dass eine Rückkehr möglich wäre. Manche Einstellung, die Kamera steht in Felshöhlen und filmt durch die beengte Öffnung das Geschehen, lässt ohne weiteres vaginale Symbole entdecken, und der Arzt der Schule, der die zwei Wiedergefundenen untersucht, die vielleicht nicht den Mut hatten, sich weit genug fortzudenken, sagt in beiden Fällen, um die Schulleiterin zu beruhigen: "Sie sind völlig intakt!" Ein schlichter Satz eigentlich, im Kontext gesehen jedoch eine Ungeheuerlichkeit. Ein atmosphärisch unglaublich dichter Film, der ganz von der einfühlsamen Kameraarbeit Russell Boyds lebt und keine besonderen Effekte braucht, um unheimliche Spannung zu erzeugen. Die Panflöte von Gheorgiu Zamphir trägt das Ihre dazu bei, um den unwirklichen Charakter des Films, sein Schweben zwischen Traum und Wirklichkeit, und damit zugleich seine Gratwanderung zwischen den Prinzipien der Lustfeindlichkeit und der Lebenslust zu unterstreichen.

Die unglückliche Sarah, man ist fast geneigt, ein Liebesverhältnis zwischen ihr und der verschwundenen Miranda zu unterstellen, jedenfalls hält diesen Druck und Zwiespalt nicht aus. Sie stürzt sich vom Dach des Internats ins Gewächshaus, lieber tot in üppig sprießenden Blumen als in einem lebensfeindlichen Gemäuer lebendig begraben.

Hans Messias, Reclams elektronisches Filmlexikon

Children in the Bush:

Picnic at Hanging Rock

He reminded himself that he was in Australia now:

in Australia, where any-thing might happen.

In England everything had been done before:

quite often by one's own ancestors, over and over again.

—Joan Lindsay, Picnic at Hanging Rock

Picnic at Hanging Rock established Peter Weir as a master in creating an uncanny, dreamlike atmosphere. It was among the most successful Australian films of the 1970s. Opening in Adelaide on 8 August 1975, it gradually became a symbol of the Australian film revival. It was shown in several countries (in the United States as late as 1979, after the success of The Last Wave) to critical acclaim mirrored by box-office triumph. Though originally ignored by the jury of the 1976 Australian Film Institute Awards, Picnic at Hanging Rock won the 1977 British Film Institute Award for best cinematography (Russell Boyd) and many other awards at smaller international film festivals.

Picnic at Hanging Rock tells the story of a group of schoolgirls from an elite private school,Appleyard College, who, on St.Valentine's Day in 1900, take a field trip to Hanging Rock, a sacred Aboriginal ground located on the edge of the Australian bush. Two of the girls and their mathematics teacher never return. In spite of the frantic search and persistent investigation by the police and by the locals, the Hanging Rock mystery is never resolved. Many questions are raised in the film, but no explanation is given.

The script, written by Cliff Green, is based on Joan Lindsay's novel Picnic at Hanging Rock, published for the first time in 1967, then by Penguin in 1970, and then reprinted many times following the appearance of Weir's acclaimed film.' Unlike the film, Lindsay's work is a nostalgic Victorian melodrama. In fact, this work resembles nineteenth century writing and is aesthetically exceeded by Weir's acclaimed adaptation, which serves as a rare example of the instance in which a film distinctly overshadows its literary source. Not only does the novel almost entirely owe its fame to Weir's film, but it is "read" through the film and interpreted in the same way.

Both Lindsay's novel and Weir's adaptation echo the way in which British encounters with an alien, Australian land have been presented in various Australian forms of artistic expression. The major theme is the European (British) intrusion into an unfamiliar enviromnent. The intruders are either rejected or defeated. Picnic at Hanging Rock shows the incompatibility of British and Australian orders. Desperate and unsuccessful attempts to preserve old orders in alien circumstances and to impose them onto the new land end in disaster.

[...] Questions raised or signalled by Lindsay were taken up by weir in his adaptation of the novel. The film Picnic at Hanging Rock is constructed around the following vivid contrasts:

- Culture (civilisation) versus Nature (Earth spirit)

- Familiar versus mysterious

- British (old land) versus Australian (Terra incognita)

- Appleyard College versus Hanging Rock

- Upper classes versus lower classes (British-Aristocratic) versus (Australian-Democratic)

As does Lindsay, Weir builds his film around the contrasts of two monoliths, Hanging Rock and Appleyard College. The film opens with a shot of an early morning scene at Hanging Rock, which towers over the surrounding landscape. From this scene a dissolve takes the viewer to Appleyard College. The awe-inspiring Rock is photographed like an old Gothic castle; as in Gothic novels or in horror films, it dominates the region and awaits its new victims. The college, and its austere headmistress, Mrs. Appleyard (Rachel Roberts), are portrayed similarly by way of a great number of low- and high-angle shots, which stress the authoritarian character end Victorian repressiveness of the school and its head.

While following the incidents and the characters in the novel closely, Weir's film concentrates on establishing an atmosphere of mystery, abandoning any attempt to reconcile the story with reality. The director traces the effects of the mystery on the people involved and the gradual decline of Mrs. Appleyard and her college without providing any explanation.

In Picnic at Hanging Rock, as well as in his other films, Weir shows the limitations of the protagonists' (and, simultaneously, our) knowledge, which fails to answer basic questions.This concept is explicitly addressed in a scene showing a small plant that closes in on itself when touched. The college gardener, Mr. Whitehead, explains to his assistant: "Some questions got answers and some haven't." Some phenomena are simply beyond comprehension. The more closely we try to observe them and understand them, the more hidden and mysterious they become. Taking this into account, it is not surprising that in its narrative, characters, and iconography, this film avoids analyses of social and cultural issues in favorof creating dreamlike illusions and a menacing spirit of mystery. Weir's film is more an oneiric enigma than a post-Victorian attempt to deal with the new land.

Picnic at Hanging Rock presents Weir's method of creating a dreamlike atmosphere from the opening shot. The following statement opens the film and appears before the credits: "On Saturday, 14 February 1900, a party of schoolgirls from Appleyard College picnicked at Hanging Rock near Mt. Macedon in the state of Victoria. During the afternoon, several members of the party disappeared without trace...."

This statement nearly explains the whole plot. The film, however, does more than recount incidents that took place on St.Valentine's Day in 1900 in an exclusive country boarding school: mystery and the experience of mystery are explored. The whispered voiceover of a line from a poem by Edgar Allan Poe, "What we see and what we seem, are but a dream. A dream within a dream," spoken by Miranda, one of the schoolgirls, and followed by Gheorghe Zamphir's panpipe music, is a more telling introduction to the film. Unlike the novel, the film is dreamlike, mysterious, and filled with implications. The book presents a more ironic view of the events, but, like the film, the novel ends as it began—an unsolved mystery.

The fatal picnic takes place in an environment described by, among others, one of the first Australian poets, Charles Harpur:

Not a sound disturbs the air,

There is quiet everywhere;

Over plains and over woods

What a mighty stillness broods.

All the birds and insects keep

Where the coolest shadows sleep…

Before leaving to go on a picnic, Miranda (Anne Lambert) warns the orphan Sara (Margaret Nelson) that she must learn to love others, and mysteriously intimates that she may not return.Then, under the Rock, each person's watch stops at noon. Miss McCraw (Vivean Gray), the mathematics instructor accompanying the girls, tries to explain this phenomenon in rational terms, suggesting that this uncanny event is caused by magnetic emanations from the Rock.

This is the beginning of the supernatural, mysterious events that occur on the Rock. The four girls, led by Miranda, remove black stockings and boots and head toward the Rock's peak.Then the girls wander through the bush, go to sleep, only to awaken in a trance and begin their exploration of Hanging Rock. The youngest of the girls, corpulent Edith (Christine Schuler), returns inexplicably terrified and, as later revealed, passes by the partially undressed teacher, Miss McCraw. Three aids and their mathematics instructor disappear without a trace.There is no explanation for the disappearance of the girls or for the later discovery of the unconscious but unharmed Irma (Karen Robson), who is unable (or does not want) to tell the truth. [...]

Picnic at Hanging Rock is replete with dream images. To create an atmosphere of mystery, Weir employs many cinematic devices, such as freeze-frames, soft focus, slow motion, and voice-over narration. Furthermore, the plot is not developed in an overly complex fashion; it remains unresolved, and there are dreamlike elements contained in the narrative. The characters have their own dreams; for example, only in a dream can Albert see the sister he has not encountered since their stay in an orphanage, while Michael has visions of Miranda. Unlike other Weir films, with the single exception of The Last Wave, Picnic at Hanging Rock is a solemn, humorless attempt to create apprehension by employing supernatural events and mysterious occurrences. Because of their unusual, Gothic-like atmosphere, Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave have been classified by some critics as horror films. However, too many elements in these films defy this type of interpretation. As opposed to standard horror films, nightmares are not the essence in Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave; rather, unknown terrains, inexplicable events, dream, and myth create a feeling of unsettling expectation.

Russell Boyd's cinematography creates hallucinatory compositions and bears a resemblance to great Impressionist painting. Dream images are intensified mainly by employing slow-motion sequences, freeze-frames, and soft-focus shots: Miranda "flows" across the creek, the four girls are shown in slow-motion scenes as they ascend the rock, and a freeze-frame of Miranda ends the film. Soft-focus photography catches the whiteness of the girls' dresses and contrasts it with the color of the rock.When the terrified Edith returns, a highangle shot shows the rest of the party in a frozen, painterly arrange meet. It bears mention that while the film employs many visual stereotypes (such as the virginal image of the girls) and trivialized cinematic devices (slow motion and so forth), it is not hackneyed because such devices purposely serve to transfer the girls from a realistic dimension to a mythical one.

The enigmatic and inspired, but occasionally banal expressions used by the girls, such as Miranda's "everything begins and ends at exactly the right time and place," also create a hallucinatory, oneiric atmosphere. Hunter, in his review of the film, writes: "Landscape doesn't embody time and place but myth." For him, the mythic, only superficially (because filled with Pre-Raphaelite "nonsense") Australian landscape is the "pictorial incarnation of that notorious Victorian malady, 'the vapors'". Preoccupied with the question of Australianess, Hunter cannot accept a work of art lacking in Australian spirit. He cannot accept that everything in the film is geared toward atmosphere.

Weir emphasizes that the most important aspect of the film, more so than the development of characters, is the creation of a "hallucinatory, mesmeric rhythm." He achieves this result not only through extraordinary camerawork but also thanks to an unusual soundtrack. He often uses eerie silence; the absence of sound enhances the sense of mystery and apprehension. In the first scene, in which the Rock is introduced, Weir employs only natural sounds from the bush (that of insects and birds) with extensive postproduction editing (magnification, speed changes, filtering), obtaining in this way a sense of the supernatural from a natural setting. Similarly, in The Last Wave, sounds of torrential rains, working windshield wipers, flowing waters, and so forth are always present. In the early scenes of both films a supernatural mood is established through haunting visual images, specific sounds, and, frequently, blocks of silence.

The atmosphere of Picnic at Hanging Rock, as mentioned earlier, is heightened by the mesmeric use of Gheorghe Zamphir's panpipe music, which, perhaps coincidentally, resembles the mood of Count Dracula horror films, set in the Carpathian mountains. In this light, the use of panpipes, as the camera scans the rock, adds new implications to the Elm. Panpipe music is contrasted with the music of Beethoven's Fifth Piano Concerto in E-flat, opus 73 (the "Emperor" concerto); the visual opposition of nature/culture (Hanging Rock/ Appleyard College) has its sound equivalent in Zamphir's"primitive" music and Beethoven's sophisticated score. A similar contrast between the European culture and a harsh Australian landscape is achieved during a garden party scene. A string quartet plays Mozart's "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" while the formally dressed guests try to behave in a way incompatible with the laws of the new land. The camera pans across the party guests and the well-maintained fragment of lawn only to reveal that the place of the party is surrounded by bush.

Color plays a meaningful role in Picnic at Hanging Rock. The first part of the film contains mainly impressionistic images: the sun and pastel colors (yellow and green hues, white) dominate the frame. In the second part darker tones appear more frequently (mainly red and brown, as in the headmistress's dark dresses and her shadowy, claustrophobic room), corresponding to Mrs. Appleyard's madness and, subsequently, her death.

There are many unresolved incidents in the film and many characters filled with many layers of meaning. As in other Weir films, there are more questions than answers: questions connected with the disappearance of the girls and Miss McCraw; the Sara/Albert relationship; and Sara's persecution by Mrs. Appleyard, resulting in her suicide.Weir intentionally leaves these and other questions unanswered, mysterious.

In the film's final sequence a voice-over commentary provides information about the fate of Mrs. Appleyard. Her body is found at the base of Hanging Rock, and it is believed that she fell while attempting to climb it. The same voice informs us that the search for the missing girls and their governess continued for the next few years without success and that their disappearance remains a mystery. These last words are accompanied by an extreme slow-motion evocation of the picnic scene under the Rock. Miranda is shown waving goodbye, and the freeze-frame of her turning her head away from the camera ends the film. The shot fades out, leaving the viewer intrigued, bewildered, mystified.

Marek Haltof: Peter Weir. When Cultures Collide

New York 1996, p 23-37

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

DVD

|

|

Criterion / Janus Films

The Criterion Collection #29 • Director’s Cut

|

|

Runtime:

|

107:00 min

|

|

Video:

|

1.62:1/4:3 Letterboxed WideScreen

|

|

Bitrate:

|

7.94 mb/s

|

|

Audio:

|

English Dolby Digital 5.1 Surround

|

|

Subtitles:

|

English (captions)

|

|

Features:

|

• Theatrical Trailer (04:48 min)

• Color Bars

• 4-Page Booklet with Liner Essay by film critic Vincent Canby

|

|

DVD-Release:

|

20 October 1998

|

|

Keep Case

Chapters: 33

DVD Encoding: NTSC Region 0

SS-DL/DVD-9, layer change at 55:44 min

|

DVD Picture 3.5: The dual-layer DVD is not anamorphic, and when viewed in component video, exhibits fine detail and definition. Contrast and shadow delineation are occasionally nicely rendered. Color fidelity delivers natural fleshtones, rich and warm colors and deep blacks. There is minor noise and artifacts apparent. Overall, the picture is easy on the eyes.

DVD Soundtrack 2.5: The remastered discrete soundtrack encoded in Dolby Digital delivers apparent electronic alterations in the surround channels. Bass has been mixed to the .1 LFE so the soundtrack could be credited as "5.1," but there is no effective enhancement. The sound is distorted overall. Dialogue, in particular, is excessively forward sounding with very poor spatial integration. Overall, the soundtrack is mono directed and undistinguished. The music score is the one element in which surround is present, but is mostly subtle.

The film master, the [...] interpositive made from the camera negative, is in good condition. There are a bit too many speckles here and image steadiness is not good enough for an 'excellent' rating, but neither problem becomes distracting. As can be exptected, this kind of master has, despite film's age, very little noise and grain. And there are also hardly any faults to find with the color reproduction or contrast range of this disc.

Sharpness is good for a not 16:9 enhanced DVD. Some shots feature astounding texture detail, usually only visible on good enhanced DVDs. It's the medium and wide shots that suffer a bit from the missing enhancement. [...] The current not enhanced version is very watchable too though, also concerning sharpness, thanks to the high quality film master and the teleciné. Sharpness is good for a not 16:9 enhanced DVD. Some shots feature astounding texture detail, usually only visible on good enhanced DVDs. It's the medium and wide shots that suffer a bit from the missing enhancement. [...] The current not enhanced version is very watchable too though, also concerning sharpness, thanks to the high quality film master and the teleciné.

Concerning video artifacts there are some minor problems, too. First, in many scenes there is some aliasing present, often in natural textures, such as rocks or trees. It's not bad, though. Then there are occasionally some overenhanced edges, but again of the not distracting kind. Finally it seems that digital noise removal has been applied, which sometimes reduces a bit the resolution of moving textures. I have seen one distracting example in chapter 5 from 2:32 to 2:34, where the stripes on the shirt of the person on the left get severly smeared during motion. This is an isolated case though, fortunately. Generally this DVD provides very film like images and does not have the video look.

Compression uses a very high bit rate of about 8 MBit/s and is without distracting artifacts. There is some I-frame pulsing, which is invisible under normal viewing conditions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg) |

|

|

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)