|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

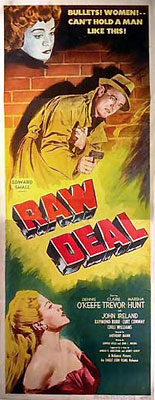

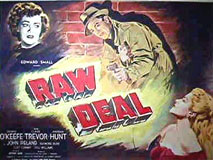

Raw Deal

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| USA 1948 | 79 Minuten

Regie: Anthony Mann Produzent: Edward Small (Edward Small Production) Darsteller: Dennis O’Keefe (Joe Sullivan), Claire Trevor (Pat), Marsha Hunt (Ann Martin), John Ireland (Fantail), Raymond Burr (Rick Coyle), Curt Conway (Spider), Chili Williams (Mercy) Premiere: 8 July 1948 (USA) | 1951 (BRD) |

|

||

|

A gangster, Joe Sullivan, is framed by his associates and vows revenge when he is released from prison. Unable to wait, he breaks jail with the help of his girl, Pat. But his old gang kidnaps Ann Martin, a stranger who sympathetically corresponded with Joe while he was in jail. As his plans to exact revenge are complicated by Ann’s presence, Joe finds a way to work her into his plans. He decides to seduce her into his world of violence and murder. A fight with the vicious Fantail ends when the losing Joe convinces Ann to shoot his attacker in the back. After this act of murder, Ann decides she is in love with Joe. Relenting, he sends her away from his nightmarish world and goes to kill Rick, the man who was a key factor in Joe’s initial frame-up. Rick’s fascination with fire becomes a method of execution. Surprised by Joe’s sudden intrusion, Rick shoots him and inadvertently starts a fire. Trapped, Rick crashes through the upper-story window to his death. Ann nestles the dying Joe in her arms as Pat resigns herself to a lonely future. Anthony Mann transcended the typically brutal environment in the gangster film and created an interesting paradox of sex and violence in Raw Deal. Joe Sullivan exists as a homme fatal seducing Ann Martin into a world filled with violent action and murder, enticing her with a promise of sexual fulfillment that goes beyond the realm of normal relationships. She surrenders completely to Joe, commithng murder as the ultimate expression of her love. Along with this apparent twist of classic noir archetypes, Raw Deal creates an atmosphere in grotesquerie and fetishism that reveals the sordid nature of the noir world. Complementing the mood and tone inherent in the film, John Alton’s photography suggests a. half-lit world magnified by the strong use of shadows and cluttered composition. The ironic narration provided by Pat, develops the romantic undercurrent evident in many noir films. It remains for the true noir film to debase any sense of pity or love that may be present, replacing it with a tough, cynical nature. Film Noir. An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style

A fine noir thriller, product of the dream marriage between Mann’s direction and John Alton’s camera. O’Keefe’s escape from jail is arranged by the racketeer (Burr) for whom he is serving a rap, and who confidently expects him to be killed, thus shutting his mouth and eliminating the need to pay him off. Along for the ride is Trevor, who loves him, and as hostage, the girl from the lawyer’s office (Hunt) who has become interested in his case. The action is sharp, the characterisation vivid (Burr gets to anticipate The Big Heat by hurling a bowl of flaming brandy over a girl who annoys him; Ireland is memorable as a cool hood who gets his kicks by needling the nervous Burr while patiently building card houses). But what gives the film its wholly distinctive flavour is the voice-over narration by Trevor. “She’s getting under his skin,” she sadly comments as Hunt’s initial flirtatiousness turns to disgust, thereby sparking a yearning to O’Keefe for his own lost innocence; throughout, her despairing efforts to understand the romantic ramifications in which the three of them get caught lend the film an unusual emotional depth. Tom Milne, Time Out

Anthony Mann/John Alton Film Noirs Mann was one of the great film noir directors of the late ’40s and early ’50s, before he turned to big-budgeted westerns with James Stewart. All of his film noirs pack a wallop, with fast-paced action and shocking violence. But the real glue that holds this set together comes from cinematographer John Alton, who photographed all three movies. Alton was one of the great cameramen of the film noir period and these three movies represent some of Alton’s best work. Alton was rarely satisfied with conventional camera setups. As you’ll find in these three movies, Alton continuously searched for intriguing camera angles. He was particularly fond of low angle shots. When someone got thrown down a hallway or into an alley, Alton loved to place his camera just inches off the ground to catch that wince of pain as the poor soul smacked the pavement. When Dennis O’Keefe gets thrown out of a gambling joint in T-Men, the camera brings us just inches away as he bounces off the asphalt and rolls out of the path of an oncoming car.

Alton always strove to reinforce the depth of the images by arranging actors in several planes in front of the camera. Whereas many directors of cinematography would simply arrange for two actors to be equal distance from the camera, Alton loved to give us one actor up close, preferrably turned sideways to the camera, while another actor stood in the background. In T-Men, we see Dennis O’Keefe’s profile as he grimaces in pain as Charles McGraw twists (and threatens to break) his fingers. And in Raw Deal, Raymond Burr lights some candles while O’Keefe gets the drop on him and steps into the back of the room. Alton’s desire to create the illusion of depth also meant he used objects in a room to break up the frame, such as the light shade in T-Men: Alton shoots the scene by placing the camera below the lamp as O’Keefe and Wallace Ford inspect a counterfeit dollar, shooting up through the lamp shade and right into their faces. And in Raw Deal we get one of the hallmark shots of film noir: O’Keefe stands behind a venetian blind, the room sliced into horizontal slats of light as he peers down at the street. Alton also loved fog and steam and smoke. In He Walked by Night, Richard Basehart flees across a foggy alley as a car’s headlights swing toward him, and later he struggles to get out of the Los Angeles sewer by pushing open a manhole cover—but smoke from a tear gas bomb envelopes him. And in Raw Deal, O’Keefe gets cornered in an alley as a thick fog threatens to obscure the action. In T-Men, several scenes take place in a steam bath, while the camera slips in close to show the beads of perspiration on the men’s faces. Alton also loved shafts of light, such as the burst of light, like a lighthouse beacon, that blasts through the small window on the door of the steam bath in T-Men. And in Raw Deal, Alton gives us stunningly beautiful shafts of moon light that break through the forest tree tops and cascade down a hillside. Alton’s used the same approach for T-Men and He Walked by Night as he did for Raw Deal, which doesn’t use a narrator and tells its story strictly from the side of the crooks. As a result Raw Deal works the best dramatically. It’s a tightly woven tale of fatalistic action. Several images jump to mind immediately, such as Claire Trevor’s face in profile as a clock continues to tick in the background. Alton frames the clock beside her face as the ever present lighting from the side casts an angular shadow along the wall. The composition tells us clearly and elegantly what no narrator could say: Father Time is one tough customer and he’s not going to let Trevor and her lover O’Keefe escape without one last fight. Or try the movie’s stunning climax as O’Keefe and Raymond Burr duke it out as the room catches fire and Burr tries to push O’Keefe into the flames. For these reasons, Raw Deal is the real gem of these releases and it’s the one movie to buy if you can afford only one video in this set. But be sure to see all three movies. These are gorgeous movies that serve as testament to the power of black-and-white photography. But these movies aren’t just showcases for flashy images. Director Anthony Mann was a master of pacing, and he guides you through the narratives at breakneck speed, while delivering some nice bits of characterization along the way. […] But to say these movies are Anthony Mann movies isn’t quite accurate. This set of film noir classics presents as good an argument as any that filmmaking is a collaborative art and that the contribution of the cinematographer can easily be as important as the director’s. They also serve as a fitting epitaph for the career and artistry of John Alton, who died in 1996.

La première période d'Anthony Mann, très sous-estimée en France, consiste essentiellement en thrillers nocturnes, tendus, obsessionnels, les meilleurs étant admirablement photographiés par John Alton, dont l'utilisation des ombres, des sources lumineuses, de la profondeur de champ (il n'éclaire souvent que le premier plan et un élément tout au fond de l'arrière-plan), de la lumière directionnelle prend au pied de la lettre la notion de film noir. Alton pensait faire une photographie réaliste, pourtant, la réalité est totalement interprétée, restructurée, recréée. La texture de l'image, le rythme des plans cristallisent une atmosphère paranoïaque, un sentiment de menace perpétuelle, une inquiétude viscérale, compressent ou dilatent le temps et l'espace. Les premiers plans de T-Men, l'assassinat d'un indic dans une usine, méritent d'être disséqués dans toutes les écoles de cinéma pour la manière dont la mise en scène joue avec les distances, les variations de cadre, l'échelle des plans, crée un climat étouffant où la traîtrise, la violence, la peur sont saisies avec une instantanéité aiguë, bref donne son vrai sens à la séquence, première plongée dans un monde impitoyable, miroir déformant de la société normale. Idem pour Raw Deal dont l'ouverture reste stupéfiante d'ingéniosité. Confrontés comme dans Reign of Terror à des décors rudimentaires, voire absents, à des budgets minimes, Alton et Mann inventent à chaque plan des solutions visuelles : une évasion est filmée du siège arrière d'une voiture, les lumières, les phares palliant l'inexistence du décor. Dans Reign, ils utilisent avec l'aide de William Cameron Menzies des miroirs pour agrandir les lieux et multiplier les figurants. On retrouve cette invention visuelle dans la poursuite de He Walked by Night, tournée dans les égouts, qui tranche sur le reste du film dirigé par Alfred Werker (une autre scène porte la marque de Mann : celle où Basehart s'extrait une balle avec une efficacité froide presque mécanique). Dans tous ces films, la violence est à la fois sèche et graphique, qualités que l'on trouvait déjà, de manière plus fugitive, moins contrôlée, dans Railroaded voire Desperate. Elle n'exclut pas un certain sadisme : dans Raw Deal, Raymond Burr envoie une poêlée de crêpes Suzette dans le visage d'une jeune femme, John Ireland et Dennis O'Keefe s'affrontent dans une des bagarres les plus brutales du genre, Mann évitant portant toute complaisance là comme dans ses westerns ultérieurs. Jean-Pierre Coursodon, Bertrand Tavernier:

Raw Deal: The Case of the Flamin’ Man “Shoot it! It’s a monster!” “Bet he’d squish like a watermelon if you stepped on him.” It is usually said that Raymond Burr was a villain who became a hero. “Villain” is inadequate to define Burr’s early roles, however. He did not simply play Bad Guys. He played Creeps. Slobs. Geeks and Sadists. Losers. Cripples. Deviants. Cowardly men, Epicene men—Fat-bellied men so fundamentally unmanly that even the women in the picture acquire machismo in comparison to him. He was not merely evil. He was abject. He was Other. When a Burr Creep walks into a scene, the other characters shrink to the edges of the frame in instinctive loathing. We loathe him, too, even before he does anything. He always does plenty of things eventually to justify our initial response: taking out his cigarette lighter and singeing the ear of his gunsel, for instance. But his soft-bellied presence is enough in itself to promote disgust. We wait, salivating, throughout each picture for this moment--the moment when the soft, cowardly man is stomped and squished. Whipped, humiliated, beaten, bludgeoned, shot, shattered, burned. His brains beaten out with a firepoker. We like to see that sort of thing. We are justified, clean of conscience. He has asked for it. His fat belly asks to be hit (and it often is). It is the site of everything that is “fem” and wrong in him. It is where he takes the shot. The most disturbing of Burr’s early fe/male villains is “Rick Coyle” of Cork Screw Alley in Anthony Mann’s fascinating 1948 film Raw Deal, photographed by the great noir cinematographer John Alton. The film is grotesquely violent even by Mann’s standards. As in many other of his pictures, fire and flame are the ultimate source of human pain. Burr’s “Rick Coyle” is the flamin’ creature who incarnates that complex metaphor in his flesh. Dennis O’Keefe plays the protagonist, “Joe Sullivan,” who is serving time for a robbery, having taken the rap for Coyle and his henchmen. They owe him when he gets out--if he gets out and lives to collect. With the help of his moll/partner “Pat” (Claire Trevor), Joe escapes and comes looking for Coyle. Coyle has arranged for Joe to be killed during the break-out in order to avoid confronting him. The failure of this scheme plunges Rick into a state of incipient terror, which he tries (unsuccessfully) to conceal from his henchmen. He now must have Joe done in some other way, by somebody else. Coyle is brutal but, like most of Burr’s noir villains, an extreme physical coward. In the course of their flight, Pat and Joe kidnap a moralistic social worker, “Ann” (Marsha Hunt) who has been visiting Joe in prison, trying to reform him. He comes on to her crudely, then begins to fall in love with her. She is alternately attracted and repelled by him--or rather, attracted to the inner “goodness” she thinks she sees and repelled by his overt violence and cynicism. Pat loves Joe unconditionally, just as he is. She does not want to change him, even though he dominates and beats her. She stands by her man—or wants to. She is pathetically jealous of Joe’s sudden attentions to Ann. Most of the film involves the complex emotional interactions within this odd menage a trois: Joe, Pat, and Ann. In choosing between Pat and Ann, Joe is really choosing between alternate versions of himself: the hard Joe and the soft Joe. His continued link to Pat defines him as hyper-macho, protected, unowned. Although she is female, she allies him with the world of outlaw men. Ann brings out the other side of Joe, his yearning for love and surcease, culminating in a fantasy of normative domestic life with her (the wife, the kids, the nice clean house). One of the ongoing issues in the film is whether or not this latent “softness” in him is dangerous to his survival (read “identity”) as a Man. The answer is yes. Fatally dangerous. If one wants to (it is not required), one can read a subtle bisexual subtext into this plot. Although Claire Trevor is quite feminine, the name of the character she plays (“Pat”) is androgynous in a way that the name “Ann” is not. Pat is not simply Joe’s “girl.” She is his “partner.” The film adopts Pat’s perspective. She is one of the few women characters in noir who is allowed to do the voice-over narration. This does not mean that the film has a female, much less feminist, point of view, however. Far from it. Pragmatically and emotionally, Pat’s interests are implacably opposed to the values of the “family nest” (read “net”) which Ann represents. Pat validates Joe’s hardness and the necessity of binary constructions of gender (“hard” vs. “soft”). She loses in the end, but not because she is wrong. Ann loses, too. Joe dies. His fragile identity has been torn apart by the conflict between the “women”--the conflict within him. Free and clear at last, ready to sail off to a new future with Pat, he goes back to save Ann, sacrificing his life for “love” and long-shot dream of domestic bliss. Ann puts her arms around him and nestles him, as he bleeds to death on the street. It is an ambiguous image.

We can have no empathy with such Creatures. Whatever residual temptation we might have to do so is immediately eliminated in the first moment we see Burr as Coyle. He is doing a Laird Cregar impersonation again, and a very outré version of it (although, in fairness, one should add that Cregar, who had a very short career to begin with, had been dead for four years, and the part now rightfully belonged to Burr himself). He is fat, soft, the curvilinear lines of his face and form emphasized by the low camera angles. He is wearing a floral dressing gown (read “dress”) and smoking from a long cigarette holder. He has a gaudy ring on his right hand. His hair is slicked down. His voice is whispery—“spidery.” His mouth is sensual-obscene, especially when it smiles in pleasure at somebody else’s pain. That sadistic administration of pain comes immediately: as Burr walks past his henchman Spider, he flicks his cigarette lighter and runs the open flame along the man’s ear. He laughs at the scream. This is his idea of a tasty joke. Throughout the film, Burr will continue to toy compulsively with the lighter, never letting us forget that opening moment--or the much more appalling scene to come. We know from the beginning how this unmanly man will meet his death: in flames. Coyle sits with Fantail who is building a house of cards on a table. Rick explains, coyly, how he has set up Joe’s ostensible escape in order to eliminate him. He has no sense of honor or loyalty. He is a coward: “You always get somebody else to pull the trigger for you,” Faintail comments, with amused disgust. (He is a low-life himself, but not that low.) Coyle is beyond shame. He takes his middle finger, extends it in a frank obscenity, and pushes it down on the house of cards, collapsing it. This is what he will do to Joe. Fuck him. Whom Coyle fucks and does not fuck is a central issue in this film—and there is suprisingly little metaphorical disguise about it. This is a Queer Text, albeit in rather different terms than Desperate. In Desperate there is a subtly positive valuing of male love and loyalty. However twisted Walt’s love for Al is, the emotional energy of the film comes from it. Here the emotional power of the film comes from Coyle’s inability to make love to women—the ways in which he is tortured for it and tortures others in response. That torture is expressed in the metaphor of fire, burning pain, and flamin’ gestures. Significantly, Joe Sullivan is a kind of fireman manque. Trying to “bring out the good” in Joe, Ann reminds him that, as a boy of 12, he rescued a dozen fellow children from a terrible fire. He was a hero. “What happened [to that boy]?’ she asks. “Maybe there were other fires. Maybe he became a fireman. Maybe he got burned. I wouldn’t know,” Joe replies, trying to cover the emotion she has wakened in him, his memory of another possible self. The image of what it means to be “burned” culminates in an unforgettable sequence halfway through the film (and then is reprised at the end). Ann, Pat and Joe have taken temporary refuge in a lush northern forest. They have coffee, a simple meal. There is moment of respite, of “softness.” Then a forest ranger approaches, questioning. Joe is poised, ready to kill him. Ann diverts the ranger, saving his life. She turns to Joe, revivified in her loathing of his animalistic capacity for violence. “You’re something from under a rock,” she says. On that line, the view cuts to a shot of Rick Coyle. He is sitting at a casino table opposite Fantail, playing poker. He is looking at his hand, smiling slightly at his henchman. A blonde bimbo, whom we have seen lounging in the background of the initial ear-singeing scene, comes up behind Coyle and coils her arms around his neck. “This is no way to celebrate your birthday,” she says playfully. His smile fades. He freezes and becomes tense. He is visibly uncomfortable. He unwraps her arms. “Stop it...You’re making me nervous.” “But I thought we were going to have a party, not a card game.” Coyle ignores her and reaches to rake in the pot. Fantail stops him and shows his own cards: “Guess this just isn’t your lucky day,” he says with a mocking smile. Rick Coyle is a Loser, in every way. And everybody knows it.

“You!” says Rick to the blonde. “You go dance with Brock [a henchman]...or the waiter.” He rips her hands off his shoulders. “You’re bothering me!” He stares darkly off into space as she obliges him with a broad smile and moves to dance with Brock, who readily embraces her. As the music plays, they circle behind him, softly laughing. Coyle looks down, unable to engage Fantail’s sarky eyes. He is rigid. He is simmering. At this moment Mann and Alton give Burr a wonderful semi-close-up. His hair is loose, coiling down over his forehead. He is oddly handsome—or handsomely odd. It would be difficult to say which. A waiter brings a special punch in a silver bowl (or perhaps the makings of Crepes Sussette). “This is for your birthday.” Coyle tastes it with a silver spoon. “Put some more Curvoisier in here, just a drop or two.” The waiter obliges. Coyle takes out his lighter and ignites the mixture. “That’s beautiful,” he says, mesmerized by the flames. Fantail begins to tell Rick about Joe’s escape. He is amused by the fear in Coyle’s eyes and the sudden nervous movement in his hands (the thumb rubbing the forefinger, compulsively). “A million-to-one shot,” Fantail says, mocking Coyle’s initial boast that he would fuck Joe so easily. He totes up how much Rick owes him from the poker game. It is a lot. “Sure is your birthday.” Brock and the blonde, dancing in the background, break into sudden laughter over some private joke. Coyle stands up abruptly. The blonde has been holding a drink in her hand as she dances, and her arm accidentally hits his back as he arises, spilling the liquor over his shoulder. There is a low angle shot as he wipes off his suit. No more simmer. He is burning now. He takes the bowl of flaming booze and throws it in the blonde’s face. She screams like a banshee. This is one of the most appalling acts in the entire film noir corpus (and certainly the most mysogynistic). Yet it is also extremely complex and subtle as well. In Desperate we never actually see Radak’s punch land on Steve’s mouth. Similarly, here we never actually see the flaming liquor hit the blonde’s face—though we may think that we do. (Such is the illusion of art.) We never see her face at all, in fact. What we do see is the horror and disgust in the faces of the onlookers who come to her aid and lead her away, weeping. (“He’s a brute,” one says, understating the matter.) We see something else as well, if we look carefully. At the moment in which Coyle’s slow burn flames up into open rage, Burr turns to the camera. He reaches back, grabs the fiery bowl in his right hand, and hurls it directly into the lens. That is “flamin’ in your face.” Flamin’ in our face. The punch bowl scene plays two ways at once. Two acts of torture occur, not one. What we see depends on who we are. What most people see (or saw in 1948) is what happens to the blonde: her scream, her agony. We imagine her burning face, her disfigurement. She is an innocent victim of a torturer who is inhumanly indifferent to the pain he has caused. (“Take her away. She should have been more careful,” Coyle says coldly.) What we do not see so readily is that Coyle himself has been an object of torture throughout this entire scene and has finally responded in kind. That torture is not physical; it is emotional—and metaphorical. But it does cause pain. Or, rather, it would cause pain if we could grant Coyle the capacity to feel. We do not grant him that much humanity. We have been prompted not to do so. We see him as an object. During most of the scene, the camera placement puts us in Fantail’s position vis a vis Coyle. We look at him as Fantail looks at him—and with the same mocking contempt. In effect, Fantail speaks for us, does our taunting for us. It is important to note that here Coyle is being humiliated and reviled not for what he has done or what he will shortly do but for what he is, and isn’t. It is “unmanliness” that makes him a fit target for general laughter: his cowardice in relationship to men, his impotence in relationship to women. Implicitly, he is homosexual—”homosexuality” here being defined negatively, not as a “love” but a “lack.” Faintail’s taunting of Coyle begins precisely at the moment when the blonde wraps her arms around his neck and he freezes in fear. (“You’re making me nervous.”) Coyle’s response to the subsequent mocking is to “burn.” If this were a color film, he would “turn red.” And, in fact, Burr’s performance is so intense that he actually makes us see that flush, invisibly. Coyle is being shamed. His face flames. The burning face he inflicts on the woman is not merely a random act of violence. It is a metaphorical equation. Her flaming face is a mirror image of his own. Is not her pain then his pain, in disguise? A terrible pain, a maddening pain that makes her scream and weep? Is it not what he would feel if he could feel anything... which he can’t. He is only a cartoon villain who feels nothing at all. Which is just as well for us. Because if he were real and his pain were real (which it is not), then who would we be but torturers ourselves, enjoying a little schoolyard act of taunting and humiliation. Like many of Burr’s best characters in noir, “Rick Coyle” is a set-up. It panders to our sadism while subtly indicting us for it. Having watched Coyle first burn his henchman’s ear and now burn the blonde’s face, we are absolutely entitled to our desire to see him burned alive at the stake. Screaming. And it doesn’t even matter that we would probably have wanted him burned alive anyhow, even if he had done neither of these things—burned simply for wearing that florid dressing gown and using a cigarette holder. Mann accommodates us, as always. Coyle sends Fantail to lure Joe into a trap and kill him. There is an extraordinary fight scene in a taxidermist’s shop, the heads and bodies of stuffed animals looming grotesquely in the shadows. (At one point, Joe mistakes a bear for Coyle.) At the climax, Joe overpowers Fantail, impaling him through the cheek on the horn point of an antler. Sadomasochistically-speaking, it doesn’t get much better than that! Fantail survives, captures Ann, and brings her to Coyle’s lair. He is sitting at his desk, eating an avocado by the light of a candelabra. “Elegance” is “decadence,” at least in America. The mobsters want to know how much Ann knows. “There are ways of finding out,” says Coyle. He takes out his cigarette lighter and gives it a flick. Joe and Pat are on shipboard, ready to escape to South America. She knows what has happened to Ann but is concealing it from him. At the last moment, she tells him the truth, not simply for Ann’s sake but because she knows that he is really lost to her and that her life with him in South America would be a sham. Joe rushes off in the fog to save Ann from Coyle’s torture. There is a gunfight in the street. In the dark, Coyle watches fearfully from his second floor office window as Spider and Fantail are shot. He is drinking Courvoisier. He turns to light a three-tiered candelabra. Joe comes up behind him, holding a gun. Coyle plays helpless. “You know I never carry a gun.” Joe hesitates a fraction of a second, reluctant to shoot in cold blood. (He has gone “soft.”) This gives Coyle time to reach into the pocket of his dressing gown and shoot through the folds of the cloth, without removing the gun he has hidden there. They exchange shots. Both are mortally wounded. The candelabra falls and ignites the window curtains. They struggle in the dark, Joe relentlessly forcing Coyle’s body back toward the window, finally shoving him into the flames. (Ah, yes.) As he burns, Coyle falls backward through the window and headfirst down to the street below. Squish! We should be sated, but in case we are not Mann tosses us a final tidbit. There is a process shot so we can actually see Coyle as he falls. (It is very fakey...but no more so than Hitchcock’s famous reprise of it in Rear Window.) The camera is positioned directly over Burr’s belly so that, in effect, we ride him down, looking at his terrified face as the ground comes up behind him. His arms are thrown up over his head, hands cringing. His mouth is open. He gets off two pretty good screams before he hits. Nancy Steffen-Fluhr, Newark Review

|

|||||

DVD

Considering the age of the source elements, the image is quite good. Everything is either shades of pure black or shades of pure white which makes for an eye catching image. The picture is extremely crisp and is leagues above what you see on AMC. I noticed some nics and scratches in the transfer, but nowhere near as much as I expected. Film grain is visible, but what would you expect from a film of this vintage? The blacks and shadow detail are very good. In some areas of the film, the picture gets away from the balanced black & white look and appears grayish. But that is about the only negative thing I can say about the transfer. The detail level is excellent and you’ll notice some things in the exterior landscape shots that VHS could never capture. ... This soundtrack is an impressive mono mix. The mix has a better sound and range than that of other mono tracks I’ve heard. ... There are no pops, or distortions of any kind normally associated with a film of this age. But I did detect some hiss during some quiet scenes, but it is minor. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)

As Walt Radak in Mann’s Desperate, Raymond Burr played the metaphorical parent (the “Bloody Mama”) of a dark-side “family” which exists in stark opposition to the sunny virtues of normative domestic life represented by Steve and Anne and, also, by Uncle Jan and Aunt Clara. In Raw Deal, he plays a similar role, although the parallelism is more complex and less obvious. The name of his character (“Rick Coyle”) and the name of his address (“Corkscrew Alley”) suggest the twisted deviance of his character. The names of his “family members” reinforce this suggestion: “Fantail” (John Ireland) and “Spider.” These are not men. They are “animals.” They exist outside the human continuum. They are everything that is Not Us.

As Walt Radak in Mann’s Desperate, Raymond Burr played the metaphorical parent (the “Bloody Mama”) of a dark-side “family” which exists in stark opposition to the sunny virtues of normative domestic life represented by Steve and Anne and, also, by Uncle Jan and Aunt Clara. In Raw Deal, he plays a similar role, although the parallelism is more complex and less obvious. The name of his character (“Rick Coyle”) and the name of his address (“Corkscrew Alley”) suggest the twisted deviance of his character. The names of his “family members” reinforce this suggestion: “Fantail” (John Ireland) and “Spider.” These are not men. They are “animals.” They exist outside the human continuum. They are everything that is Not Us.