|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

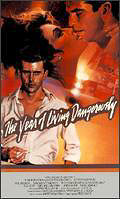

The Year of Living Dangerously

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australia / USA 1982 | 117 Minuten

Regie: Peter Weir Produzent: James McElroy Darsteller: Mel Gibson (Guy Hamilton), Sigourney Weaver (Jill Bryant), Linda Hunt (Billy Kwan), Bill Kerr (Col. Henderson), Michael Murphy (Pete Curtis), Noel Ferrier (Wally), Paul Sonkkila (Condon), Bembol Roco (Kumar), Domingo Landicho (Hortono), Norma Uatuhan (Ibu), Joonee Gamboa (Naval Officer), Coco Marantha (Pool waiter), Mike Emperio (President Sukarno) Premiere: December 1982 (Australia) | 27 Mai 1983 (BRD) |

|

|||

|

Mel Gibson once again proves there’s more to his mystique than Mad Max in this political thriller directed by Peter Weir. Set in Indonesia during the 1965 coup against President Sukarno, the film stars Gibson as Guy Hamilton, an Australian wire-service reporter covering the scene. Whenever Hamilton becomes too glib or indifferent for his own good, he is brought back to earth by his "conscience", photographer Billy Swan (played in male drag by diminutive actress Linda Hunt, who won an Academy Award for her performance). As all of Jakarta sinks into disarray, Hamilton pursues a romance with British attaché Jill Bryant (Sigourney Weaver). For the most part, the film — based on a novel by C.J. Koch, who collaborated with director Weir on the screenplay — rings true; it falters only a during gratuitious car-chase sequence, evidently added at the behest of MGM, who financed the film (the first such American-Australian financial collaboration). Filmed on location in the Philippines and Australia, The Year of Living Dangerously is one of those rare films which successfully combines real-life political intrigue with solid entertainment value. Hal Erickson, All-Movie Guide

Ambitious, gripping, and stylish, The Year of Living Dangerously falters in its attempts to be a thriller, romance, and political tract, and to encompass director Peter Weir's penchant for mysticism. Still, it's an excellent film. [...] Weir is only partly successful in attempting to link his various themes symbolically with images of Indonesian shadow puppetry and with Billy's advice to "look at the shadows, not at the puppets," but the director indisputably made the right move in his risky casting of the tiny, gravel-voiced Hunt as Billy Kwan, winning her a Best Supporting Actress Oscar and a New York Film Critics Award. The film's hot, humid, seedy ambience is nearly palpable, enhancing this fascinating story of Sukarno's downfall. This was the first Australian movie financed (to the tune of $6 million) by a major US studio. For obvious reasons, Indonesia was not the place to shoot this, so the location work was done in the Philippines. However, when the cast and crew received threats (alledgedly from the local Islamic community), the production moved to Sydney.

Beyond Shadows: The Year of Living Dangerously Without myth, the spirit starves, It's rather a bore to be half something. Since its first appearance in 1978, C.J. Koch's novel The Year of Living Dangerously has received a great deal of critical and scholarly attention. Apart from being the winner of the National Book Council Award for Australian literature and the recipient of the Age Book of theYear Award, this novel was also successfully adapted for the screen by Peter Weir, with Koch contributing to the script. Weir's The Year of Living Dangerously (1982) marked a turning point in his career. He has worked in the United States ever since its successful international release. It was also the first Australian film to be fully financed and distributed by a major Hollywood studio, MGM. The film re-creates the political climate of Indonesia in 1965. It deals with a group of Western journalists in Djakarta some months before and during the unsuccessful PKI (Indonesian Communist Party) coup, which also brought to an end the reign of President Sukarno. Sukarno, the hero of Indonesia's struggles for independence, was overthrown by the right-wing, predominantly Muslim, military establishment headed by General Suharto. During his reign, Sukarno gave each year a name; from this follows the title of the book and the film. In his Independence Day speech of 17 August 1964 Sukarno called the coming year "the year of living dangerously," in a sense foreseeing the cliffficulty of managing the country with two radical political forces, the Communists and the Muslims, both trying to overthrow his government. Certain elements in Koch's novel push the reader down specific interpretative paths. Although realistic in mode, the novel contains a mythological framework that provides a set of possible explanations for the novel's narrative. The Year of Living Dangerously is modeled on wayang Alit, the Javanese shadow theater. What is even more important, however, is that Indonesia and its culture do not merely serve as an exotic, "Oriental" background for the adventures of the Western reporters/globetrotters/observers. The indigenous Indonesian elements — the puppet theater and the last year of Sukarno's power and his downfall — dominate and structure the work. Furthermore, the Oriental element in The Year of Living Dangerously functions as the missing part of Western identity; it is the absent spiritual component of the Occident. [...] Weir's adaptation, with Koch's participation as one of the screenwriters, differs from its literary source in that while the former is politically oriented, the film moves from the political to the melodramatic within a political setting. Compared with Koch's novel, the film scarcely touches on the complexity of political issues of the East. Instead, it concentrates on Weir's favorite theme of cultural clash: here, East versus West and, more specifically, a Western (Australian) journalist facing social upheaval in a Third World country that he does not really comprehend.

Another important change from novel to film is the choice of narrator. In the book, he is a foreign journalist, Cookie; in the film he is replaced by Billy Kwan, who, apart from being the film's narrator, is also a participant and the most powerful figure in the film. Compared with weir's other filmic characters, Billy Kwan (played by American actress Linda Hunt in an Oscar-winning performance) not only straddles two worlds but also, because of his mixed parentage (Australian mother, Chinese father), combines elements of both East and West. This factor, and the fact that Billy is played by a woman, adds new meaning to the story: Billy is a mixture of male and female, of East end west, but first and foremost he is a link between these two worlds. He tries to help others overcome their inability to see and understand another culture. Hunt's role in the film is reminiscent of that played by the Aboriginal people in The Last Wave (mainly David Gulpilil's Chris). Furthermore, in some respects, the lead character in The Year of Living Dangerously, Guy Hamilton (Mel Gibson), an Anglo-Australian journalist newly arrived in Indonesia, in part resembles David Burton from The Last Wave, who, though representing the world of reality and Western logic, also tries to understand the "dream" world. Weir's "generic" culture/nature dichotomy is replaced here with the conflict of Oriental and Occidental. The West is embodied in the Western journalists. Nature finds its equivalent in the East: mysterious and incomprehensible to the outsider. As a rule,Weir is preoccupied with the presentation of a middle-class WASP character facing the inexplicable, represented in his films by the Rock, Aborigines, the Amish, and so forth. His central interest lies in presenting the relationship between the two opposing forces (nature and culture, East end west), not in explaining their sources and motifs. Somehow, he always stays on the surface.Weir seems only to need the"other side" (nature, the East) to show the limitations of his own white Western culture. Talking about The Year of Living Dangerously, the director claimed that he "wanted a rather timeless setting in [the] background. The film was about Asia . . . and the background was to reflect that". This is probably the reason that this film, like his others, may be seen as apolitical, romantic, and superficial in its treatment of social issues. This film is also a part of a larger subgenre that might be called "the adventures of Western journalists in countries experiencing political and economic turmoil." The best-known examples of these films from the 1980s are Far East (1982), Missing (1982), Under Fire (1983), The Killing Fields (1984), and Salvador (1986). Whereas some of these films often exploit their exotic setting and concentrate on the misfortunes of the native people, The Year of Living Dangerously, in spite of its traditional romantic narrative, contains a strong critique of Western ideology. Carolyn A. Durham writes that "Peter Weir's attack on western ideology is thorough and relentless to the point of challenging both his own films and certain possibilities of film itself". Durham's view is particularly relevant in the case of Koch's novel, which goes beyond the usual description of the incomprehensible, mysterious East. Instead of providing a typical critique of Western ideology, Koch concentrates on the opportunities offered by the "Orient" (here Indonesia) and its culture. The Orient is not further "orientalized" by Koch; rather, he attempts to understand and to explain its complexity. In this context, the doppelganger motif, the motif of the double, extensively employed by Koch and also by Weir, serves to point up not differences but similarities. In Billy Kwan, one of the most extraordinary figures in recent fiction and film, this idea is effectively embodied: he is a man of two worlds/cultures/races, a divided hero of postcolonial reality. The doubleness, which may be considered a very Australian topic in the context of the country's colonial heritage and its present-day isolation from the rest of the world, is the central metaphor in The Year of Living Dangerously. In Weir's film, Asia (Indonesia) does not represent a sinister "otherness" and is not a threat to WASP Australia. The distinction between "us" and "them," Australia and Indonesia, is not clear. Indonesia, the East, the Orient function—as noted earlier—as the missing part of Western identity. The Year of Living Dangerously introduces "hybrid" personalities, protagonists alienated from their home countries, who have problems with their personal identities. Both Hamilton and Kwan are displaced persons or, more precisely, men without a center. Hamilton is certain that Europe is not his Like Koch, Weir tries to go beyond the "Oriental," "exotic," and "melodramatic" elements of the Indonesian background. To organize his film as well as to add new meanings, he assimilates the ethos of wayang Alit into the story. He gives the audience an acceptable set of explanations by absorbing the notion of wayang. "To understand Java, you'll have to understand the wayang," says Kwan. Teaching Guy to look at the shadows and not at the puppets while watching a performance, Billy tries to force him to go deeper into his understanding of the East ("The unseen is all around us, particularly here, in Java"). The wayang motif, its Indonesian context, and the wayang's significance to the narrative aspect of The Year of Living Dangerously is frequently taken up by scholars. Margaret Yong suggests an interesting parallel between the wayang puppet theater and Plato's famous caved Like the prisoners in the Platonic cave, wayang watchers can also only observe shadows that stand for all real occurrences. To understand reality they must rely on its shadowy images. This ambiguous, thin delineation between what is perceived as reality and illusion is further developed by Weir in his description of Western correspondents gathering in the Hotel Indonesia's bar. As Yong notices, they are also "prisoners inside the dark cave of the Wayang Bar". Ironically, they are voluntary prisoners who retreat to the illusory shelter of a bar for foreigners in a foreign country. The motif of puppets is introduced at the beginning of the film: the wayang puppet show appears with the title credits. Later, Billy introduces the three major figures from the wayang: the hero-prince, the princess, and the dwarf who serves the prince. Billy, who equates himself with the faithful dwarf, perceives Guy as Prince Arjuna, who "is a hero, but . . . also . . . fickle and selfish." For Jill Bryant (Sigourney Weaver) he reserves the princess figure, Srikandi, "noble and proud, but headstrong, the princess Arjuna will fall in love with." The puppet motif is a carefully developed visual metaphor describing both political (President Sukarno) and personal (Billy Kwan) attempts to manipulate the people. The president balances left- and right-wing forces within Indonesia to create the impression of unity between opposites. Kwan idolizes the dictator. For him, Sukarno is successful in his attempts to find an equilibrium between the Marxist revolutionaries and the pressures from the principally Muslim military. Sukarno also stages a performance of the puppet theater for his ministers to covertly make known his will and future political decisions.The shadows stand for reality. Kwan, on the other hand, manipulates and controls other people; he keeps files on everybody he knows, and he is also a kind of accoucheur of the relationship between Hamilton and Jill. The dwarf is introduced in the film right after the credits as he prepares his dossier on Hamilton. Later, sitting in his room at his typewriter, he whispers:"Here, on the printed page, I'm master—just as I am the master in the dark-room, stirring my prints in the magic developing bath. I shuffle like cards the lives I deal with." Both supreme puppet masters (dalangs) suffer defeat. Sukarno is replaced after a short but bloody civil war by General Suharto; a disillusioned Kwan encounters death while protesting against Sukarno's policy. Like Billy, Sukarno is a man of dualities: both Hindu and Muslim by birth, a member of the aristocratic class yet a socialist, a charismatic manipulator of the masses and a demagogue, yet, at the same time, a man of considerable merit for Indonesia. The political aspect of The Year of Living Dangerously is stressed throughout, beginning with the film's opening. On his arrival at Djakarta airport, Hamilton is surrounded by anti-imperialist slogans and a hostile crowd of Indonesian poor."Don't take it personally: you are just a symbol of the West," says Kwan, his guide to the "mysterious Orient."A group of Western journalists, isolated in their hotel and its bar within a hostile and incomprehensible country, deals with the Indonesian people in the manner of President Sukarno, who, in Kwan's words,"uses the people as objects for his pleasure." Political and sexual exploitation are strictly connected in the film. The representatives of the Western World cannot—or do not want to—overcome their inability to "feel" another culture. The journalists, insensitive to the misery and suffering around them and insensible to the political nuances of Indonesia and its problems, are interested only in selling their stories. They seem to be satisfied with a voyeuristic relationship with the natives; they exploit them and observe their misery. The journalists are introduced to the audience in terms of their sexual perversions. A British journalist sexually exploits young boys. An American correspondent spends his stay in Djakarta in search of sexual pleasure. As Durham points out, "The camera... makes the connection between sexual and colonial exploitation, between erotic and ideological voyeurism". In these and many other ways, the film is reminiscent of Weir's earlier works: the incomprehensible East; bad and incompetent Westerners/foreigners; an innocent Australian; a cynical Englishman (the British military attaché, Colonel Henderson, who is portrayed as an anachronistic symbol of the Empire in the postcolonial world). But the introduction of the almost mythic Billy Kwan is unusual in that the dwarf, because of his mixed parentage, combines elements of both worlds, East and West. Weir is perhaps intentionally ironic in portraying Kwan, the strongest character in the film, as a dwarf. In Weir's adaptation Kwan is the narrator and moral renter of the film. Played by Hunt, Kwan is Eastern and Western, male and female, detached observer and passionate participants The tormented Australian-Chinese cameraman, who is the link between the two worlds, tries to understand and to help the Indonesians as much as he can. He repeatedly borrows a phrase from Luke, later used by Leo Tolstoy: "What then must we do?" He poses the same question in an emotional climax as his world rapidly disintegrates. After learning of the death of his adopted child and having seen groups of starving Indonesians fighting for rice, Kwan, with photographs of local faces all around him, cries and passionately types this very question on his typewriter.The poignant third song—"On Going to Sleep"—from Richard Strauss's "Four Last Songs" emphasizes his desperate search for a solution. Kwan finds it in another small attempt to change the reality around him; his unsuccessful struggle to attract Sukarno's attention by hanging a banner reading "Sukarno, feed your people," from a window results in his tragic death at the hands of the security forces. According to Durham, the relationship between vision and knowledge is the key to the meaning of the film. For her, this subversive, self-reflexive film "centres its critique on the conception and the function of vision". The Australian reporter, likely because of his youth and innocence, represents hope for Kwan: he brings the possibility of learning to see and feel in a new light. As a cameraman, Kwan is not only Hamilton's eyes ("I can be your eyes," he says) but also his "architect of images," combining the seeing of things with feeling them. Kwan devotes all his energy to teaching Guy to see (understood as "feel") the true Indonesia, which is not very far from the Wayang bar. Losing Kwan, Hamilton loses his only chance to comprehend the Eastern World around him.The protagonist's inability to "feel" the real Indonesia is literally presented in the final sequences of the film as his partial blindness. Hamilton's loss of vision (from a detached retina) serves as a metaphor for the West's lack of "vision," its inability to comprehend occurrences unrelated to its own cultural assumptions. In the film's final sequence, Hamilton's Indonesian assistant, Kumar (Bembol Roco), a member of the Communist Party, puts it this way: "Billy Kwan was right. Westerners don't have answers anymore. This film's main concern is the concept of the "mysterious Orient," which is beyond Western comprehension. In this context, the question introduced by James Roy MacBean in the subtitle of his article "Watching the Third World Watchers"—"Mysterious Orient or, Merely the Insensitive Western Observer?"—is of crucial importance. Another important aspect of the film is the voyeurism of Kwan and the foreign correspondents. As compared with the exploitive journalists, Billy Kwan is the more complex voyeur. Because of his inconspicuous appearance, he chooses a handsome alter ego (a double) in Hamilton and thereby embellishes his image. When Kwan is convinced that his doppelganger is equipped with all of his virtues, he introduces Hamilton to Jill, a secretary from the British Embassy, with whom Kwan is in love.When Billy realizes that she does not love him, the dwarf promotes his "substitute" and gets pleasure from being close to the lovers. Then, he controls their actions, offers his flat to them, spies on them, photographs them, and adds to his dossiers on them. Moreover, when the romance becomes a source of disappointment for him, he tries to put an end to it. "I believed in you," Kwan tells Hamilton,"I made you see things, I made you feel something about what you write, I gave you my trust, so did Jill . . . I created you!" At first glance, Hamilton and Kwan seem an unlikely pair: a physically attractive, eager Anglo-Australian journalist and a tragicomic, megalomaniac Chinese-Australian dwarf. But as Kwan says, they "make a great team . . . you for the words, me for the pictures. I can be your eyes." Both Hamilton and Kwan are `'incomplete human beings": they have to rely on and supplement each other. On the one hand, Hamilton is an "object of desire" and worship for Kwan, on the other, an object of manipulation and re-creation. Jill touches on the true motif of Billy's actions when she notes that Hamilton is "everything [Billy] wants to be." Kwan makes efforts to subordinate and shape Hamilton. Nonetheless, as in Gothic novels and horror films dealing with the relationship between the creator and the creature/monster (the Frankenstein motif), the creature becomes a source of disappointment for the creator, who inevitably cannot completely control his creation. Kwan's character combines both voyeuristic and puppet-master elements.When the puppets gradually slip out of his hands, his role (like that of President Sukarno) ends. Kwan has carefully engineered relationships with others (Sukarno; an Indonesian woman, Ibu, with a child he supports; Hamilton) and between others (Hamilton and Jill); nonetheless, this construction collapses. Like Sukarno, Kwan cannot control his creation: the puppets he once controlled slip out of his manipulative grasp to take on lives of their own. A puppeteer without his puppets is a figure of no importance, a master without slaves, a Dr. Frankenstein without his laboratory. The tragic death of Kwan serves to emphasize this moment of helplessness. The Year of Living Dangerously is Kwan's film, and his presence adds an important dimension to it. The film begins with Kwan and his voiceover comments introducing Hamilton; the audience then sees most of the events from his point of view. His voice-over narration infuses the film with a dreamlike mood. Kwan's death marks the real end of the film. When Kwan is no longer on screen, The Year of Living Dangerously rapidly lapses into a cliched Hollywood film. For the first time in his career Weir employs in The Year of Living Dangerously the motif of romantic love, which he also presents in his next film, Witness. Interestingly, Jill and Hamilton's romance, though it seems to dominate the film, is less important than Guy's relationship with his"creator," Kwan. In presenting and developing the romance, Weir is conventional. Both lovers look as if taken from an American dream: they are handsome, independent, ambitious individuals surrounded by the exotic and impoverished masses. Some sequences are familiar from hundreds of films (their eyes meeting across the room; the happy ending—reunion and embrace), end weir does nothing to modify these adopted images. On the contrary, as in his earlier films, the director does not attach much importance to "the story." For Weir, "the story" is always only a pretext through which to present ideas, and he does not even try to mask his intentions. He easily employs recognizable, only intensified images to fix audience attention on ideas. The oneiric aspect of the film is achieved through consciously employed visual images. Russell Boyd's photography captures the tropical, beautiful, but hostile Indonesia. The characters move in this dreamlike landscape as if driven by an invisible force. Some sequences possess a nightmarish quality. The best examples of this are the shots of Djakarta when Guy arrives on his first foreign assignment, the images of poverty-stricken Indonesians, the bloody military coup and Guy's desperate drive to the airport, shots of mist rising off the canals, the slums of Djakarta, and a tropical downpour. Moreover, Weir also employs a "real" nightmare, Hamilton's troubled dream of drowning, which, incidentally, plays on the familiar Weirian water motif. Frequent shots through the windshield of Hamilton's car help to create a hallucinatory atmosphere. Oneiricism is enhanced by the use of shadows, which also call to mind the puppet motif.They appear at the beginning of the film, there during the love scene (the shadow of kissing lovers), and when Hamilton broadcasts his first report (a silhouetted shadow on the window). Maurice Jarre's music plays an important role in generating this dreamlike mood; its tone mainly stresses the romantic. In his first four feature films (Picnic at Hanging Rock once again being the best example), Weir "discourages" the spectator from following the story. Gallipoli and, especially, The Year of Living Dangerously, in spite of their more linear narrative lines, only appear to work differently. By presenting an easy-to-follow plot, Weir concentrates on creating an unusual mood and on exploring themes interesting to him, this time not hidden in the narrative line but rather apparent, even obvious. It is possible to say that since Gallipoli Weir has changed his method of presenting a story, but this does not mean he has changed the content. For some critics, The Year of Living Dangerously is the pinnacle ofWeir's earlier works. He successfully employs a conventional narrative structure and yet is able to infuse it with a recognizable personal style. Marek Haltof: Peter Weir. When Cultures Collide.

Weir’s film, like Koch’s novel, offers a considerably simplified account of events preceding the coup attempt on 30 September 1965, with its amalgam of fact and fiction, recollection and supposition, relation and dramatisation of actuality. It is debatable if a commercial film could be made from the many theories still surrounding the Sukarno regime and its demise. However, the most contentious feature of Weir’s film (with only slight variance from the novel) was its conclusion —’an ending to surpass bygone Hollywood at its silliest’. Other critics have detected the influence of American film history (but nonetheless continued to express dismay at Year’s failure to be a political or realistic film), explaining Koch’s and Weir’s simplification of the novel’s ending thus: "He has only made period pieces … and above all uses the sum of his skill to imitate the workmanship of American ’B’ pictures of the ’50s … into the Indonesia of Sukarno … Peter Weir transposes all the narrative patterns of a romantic, exotics and unpretentious cinema, haunted no doubt by the memory of Casablanca." Such analogies may not be mistaken, particularly when one considers Sigourney Weaver’s memories of Weir’s direction of the two stars: ’Weir had to teach the couple how to kiss for the screen by showing them clips of Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman from Notorious.’ The director may well have encouraged an artificial, referential performance from his relatively inexper fenced actors, coaxing them to give imitative characterisations This re-emphasizes the self-conscious and intertextual tone of both Gallipoli and Year. Their place within the conventionalised canon (of genre film and of Weir’s work) can be recognised through their period placing, thematic and visual stylisation and predetermined narratives, without detriment to their modern philosophical concerns framed in past (film and national) history. The viewer informed by history for Gallipoli is replaced by one formed by cinema and genre history in Year, with the stylization of both (the three-act structure and Wayang reference) highlighting prior knowledge and predestination of narrative and character. Their modern frames are dictated by cinematic and social history, with themes emerging from the myths of both. In Gallipoli and Year, Weir has continued the accommodation of, or homage to, American genre cinema, while retaining his own distinctive traits of mysticism and visual poetry, which would be met with greater acclaim in Witness. Where The Cars That Ate Paris (1974), Picnic and Wave combined Australian culture and generic cinema with popular and high-art forms of America and Europe, these two films show a development of Picnic’s interplay of reflexivity and fact, the awareness of Cars and Wave of American genre cinema and a further integration of recurrent stylistic features (music, editing, art direction becoming art consumption). These tendencies emphasize the continuities within Weir’s work, despite the popular belief that his characteristic style has faded with the predominance of narrative over atmosphere, of genre over art. Yet the director’s art-film reputation must be attributed as much to the reinvocation and reinterpretation of genre as to significant art direction, editing, sound and narrative ambiguity. Guy and Jill are moulded and ’directed’ by Billy, even as all three are constrained by genre, itself being transformed by Weir. Archie and Frank are impotent protagonists within a stylized and reflexive, modern and revisionist syuzhet, rather than fully formed personalities within a historical fabula. Their embodiment of contemporary innocence and modern comprehension makes an understanding of the reasons behind the events, within both the factual and diegetic contexts, extremely difficult. This tendency in factually based films such as Gallipoli and Year makes the mystery of the quasi-historical Picnic, the amorality of the anti-Western Cars and the inconclusiveness of Wave’s subjectivity easier to accept as an openness to a plethora of meanings rather than an unwillingness to complete narrative. Year adopts an Indonesian art form despite the fact that the journalists within the diegesis live isolated from the country and fail to understand it politically or culturally. In the end, all Guy can do is leave, returning to the West after filing his melodramatic, opinionated ’stories’: ’Unlike the moment of Casablanca, there is no stark choice to be made here between neutrality and commitment — only the recognition that these events offer no place for the Western loner to insert himself as hero.’ The legend of Gallipoli can only be approached by a modern audience through the popular perception of the First World War in general and the campaign in particular. The musical tropes of Weir’s film betray our contemporary knowledge of the past tragedy (Albinoni), and the temporal distance over which we (re)view it (Oxygene). The film’s punctuation with titles giving dates and locations is only a form of stylization comparable to the rarefaction of history into myth. In Year, Weir takes the features of two art forms — the innocence and simplification of generic constructs from past cinema and the parables and symbolism of the Wayang — and creates a visual polyglot, keeping both in view while eschewing an ultimate Western distinction or judgement. He produces a synthesis, balancing popular genre and art like Billy’s ’opposite intensities’. The screenplay and visual conceits, mating the novelistic and historic sources, devotional Wayang drama and classical cinema, together with Weir’s own mystical and humanistic concerns, are faithful to the auteurist development of genre film. It is ironic that these two films, held up as examples of Weir’s developing skill in cinematic narrative, should concentrate on the difficulty of relating and interpreting stories. The framing of these narratives within factual and cinematic history, as well as within the director’s own stylistic structures, portrays the maturation of his heterogeneous film idiom, combining the details of art film with the signs and settings of genre, and the focus on story-based film with the laying bare of the problematic processes of narration. On the threshold of acceptance into Hollywood, the director continued to familiarize himself with the heritage of generic cinema, at the same time defamiliarizing its features within his own work. Jonathan Rayner: The Films of Peter Weir.

Was ist dieser Film... Magie, irgendeine Art von Zauber, in dem all das zusammenfließt, was Kinoglück und Lebenssehnsucht ausmacht — nie ganz greifbar, unbegreifbar... Leinwand-Eskapsismus und Fernweh, vergangenes Melodram und vertrautes Land, reale Tränen und fremde Exotik — die Erfahrung, etwas zu empfinden, aber doch nie verstehen zu können. Die Magie von Peter Weir, aber sehr viel mehr noch die Magie von The Year Of Living Dangerously(...)

Das kann eine exotische Kultur ebenso sein wie eine künstliche TV-Welt (The Truman Show), das entrückte Uber- und Weiterleben nach einem Flugzeugabsturz (Fearless) genauso wie eine abgeschaltete Sekten-Gemeinschaft (Witness), ein illegaler Franzose im heutigen Manhattan (Green Card) wie Australier im europäischen Weltkrieg (Gallipoli) oder ein sinnesfreudiger, unkonventioneller Lehrer in einem Bestrengen Elite-Internat (Dead Poets Society). Fritz Göttler sieht Year in der Tradition der Romane von Eric Ambler und Graham Greene: „ Eine atemberaubend genaue Analyse der weltpolitischen Entwicklung durch das genaue Studium der menschlichen Emtionen ". Man könnte noch Joseph Conrad mit dazu nehmen, nicht so sehr den „apokalyptischen" (Ver-) Führer ins Herz der Finsternis als den Autor von Victory. Weirs Filme sind also eigentlich eher Ethno-Dramen, Ethno-Melos. (Wenn der Begriff "Ethno" nur nicht so modisch abgenudelt wäre!) Und ein weiteres Element, eine weitere Facette, gewissermaßen eine vveitere Rolle, spielt dabei die Musik von Maurice Jarre, die Weir so gerne einsetzt. Lange habe ich sie als verstörend, ja störend empfunden. Weil sie immer, obwohl auf ethnische, eher sogar folkloristische Formen zurückgreifend so eine glatte, süßliche Synthetik des europäischen Pops vor sich herträgt. Aber auch das macht die Magie aus, daß diese Ohrwürmer, die sich so säuselnd der Sinne bemächtigen, zugleich schmerzen, eine sonderbare Distanz schaffen. Letztlich also den Ton von Weirs Ethno-Melos angeben. Der Preis, den Weirs Figuren zu zahlen haben, um die Grenzen des Fremden zu durchbrechen, hinter die Kulissen zu blicken und scheinbar etwas zu verstehen oder gar zu verändern, ist immer hoch. Ist immer mit einem Verlust verbunden, einem physischen oder psychischen Defekt, der die Liebe oder gar das Leben kostet von Menschen, die dem Helden, der natürlich nie ein klassischer ist, nahestehen. Um am Ende doch nichts wirklich verstanden zu haben. Im Reich der Schatten: Der Film beginnt mit einem Wayang Kulit, dem traditionellen indonesischen Puppentheater, das wie ein Scherenschnitt-Spiel funktioniert. Vor einer Lichtquelle agieren hinter einer Leinwand zweidimensionale Figuren; ihre stark typisierten Silhouetten erscheinen auf dem Stück Stoff als Schattenriß. Ein Mysterienspiel, in dem sich Ahnenkult und frühe Sagen, Hindi-Epen und islamisches Bilder-Verbot bündeln. Kino, über 2000 Jahre alt. „Du must auf die Schatten achten!", sagt Billy Kwan später einmal zu Guy Hamilton, als er diesem drei Puppen vorführt, die Guy in seiner Wohnung entdeckt hat. „Das ist Prinz Arjuna, der Held der aber auch launisch und selbstsüchtig ist. Und das ist Prinzessin Sirkandi, edel und stolz — Arjuna wird sich in sie verlieben." — „Und was ist das?", fragt Guy lachend über eine dickliche Gnom-Figur. — „Das ist Semar.Er spielt eine ganz besondere Rolle — er dient dem Prinzen", klärt ihn Billy auf. Also doch eine einfache Geschichte, eigentlich. Aber Guy nimmt dieses Fanal nicht ernst, hält es für Folklore, statt sein Fatum hinter den Schatten zu erahnen. Denn Guy weiß Bilder nicht zu deuten. „Dein ist das Wort, und mein ist das Bild" beschwört Billy Guy, als sie erstmals ins Geschäft kommen. Guy bekommt sein exklusives Interview mit dem Kommunisten-Chef, Billy darf dazu fotografieren: „Ich kann dein Auge sein!" — Am Ende wird Guy ein Auge eingebüßt haben, weil er nicht sehen wollte, nicht sehen konnte. „Ich habe an dich geglaubt, ich habe geglaubt, du seist ein Mann des Lichtes", empört sich Billy, weil Guy Jills vertrauliche Inforrnation über eine große kommunistische Waffenlieferung in einen Medien-Scoop umgemünzt hat. Jill wollte Guy persönlich vor dem Bürgerkrieg warnen, (Um hat eine journalistische Warnung an die Welt daraus gemacht — und vor allem Karriere-Punkte für sich. „Ich hätte die Welt für sie gegeben", verzweifelt Billy, „und du opferst nicht mal eine Story für sie!" — Guy versteht ihn nicht: „Es ist die Story!!" Die Schatten von Liebe und Loyalität: Für Billy ist es unbegreiflich, wie man einen geliebten Menschen so verraten kann, aberund das ist das unbeschreiblich Grausame an dieser Szene — er weilt, daß Guy letztlich irgendwo mit seiner Entscheidung recht hat. Mit der historischen Einschätzung und dem persönlichen Verrat. Denn auch Billy muß etwas verraten: sein geliebtes Idol Sukarno, der sein Volk, wie er gerade zuvor bitterlich erfahren hat, in Hunger und Tod treibt. Diese nächtliche Auseinandersetzung mit Guy hat etwas Gespenstisches — im Hintergrund kleben Sukarno-Plakate, die von kommunistischen Graffiti gezeichnet sind. Das eine, das zentral hinter den beiden hängt, ist mit einem roten Hammer-und-Sichel-Emblem übermalt. Und das Schlag-Eisen trifft Sukarno so zwischen Mund und Nase, daß dessen Gesicht wie eine Hitler-Fratze anmutet. The Horror, the horror... Die Zeichen der Zeit sind an die Wand gemalt, aber man muß sie erkennen können. Kurz zuvor gibt es zwei Schlüssel-Szenen, so betörend und verstörend: Guy Zwei extrem intensive Szenen, in denen das lebenspendende Wasser zur Todesmetapher wird. Zwei Szenen, die die Ambivalenz von Peter Weirs Blick exemplarisch in sich bergen: Uber der ersten lastet schwer eine tödliche Bedrohung, während einem die atemraubende Szenerie schier den Kopf wegbläst. Und in der zweiten treibt es einem gnadenlos die Tranen in die Augen, weniger ob des Todes des Jungen, als vielmehr wegen des zärtlichen Ritus, mit dem der Abschied zelebriert wird. Eine reale Tragödie, die ihre Schatten auf Billy wirft. „Alles ist durch unsere Wünsche getrübt, wie das Feuer durch den Rauch, wie der Spiegel durch den Staub", hatte Billy einmal für Guy die Wayang-Gottfigur Krishna zitiert. „Sie blenden unsere Seele." „Was sollen wir nur tun, was sollen wir nur tun!?" martert sich Billy zuhause und blickt in die Augen der Menschen, deren Blicke er über die Jahre auf Fotos dokumentiert und in seiner Wohnung an die Wand gepinnthat. Ausgezehrte Gesichter, flehende Mienen. Leere Augen, lethargische Blicke, die auf einmal an Billy zu appellieren scheinen. Er zieht die Konsequenz aus seiner Blendung, protestiert bei einem Empfang gegen den Staatschef mit dem Transparent „Sukarno, Feed your People!" und wird von dessen Schergen umgebracht. Die Ambivalenz des Blicks setzt sich bis in den Tod hinein fort: Als Guy den Kopf des Sterbenden zärtlich in Händen hält, oszilliert dessen Antlitz zwischen einem toten Lächeln und einem lächelnden Tod. Sehen und gesehen werden — nicht im Party-Sinn, sondern ganz ursprünglich: Sehen und Erkennen. Peter Weirs Unversum ist ein Kino der Blicke, der Ambivalenz des Blicks. Was für das Wie ebenso wie für das Was gilt. So wie sein Point of view nie manipulativ ist, einem keine definitive Sichtweise aufnötigt, so ist der Blick der fremden Welt, der einem aus seinen Filmen entgegenschaut, immer mehrdeutig. Gesichter, Gesten und Mienen, die jenseits des ersten Anscheins alles oder nichts bedeuten können. Alles zwischen Leben und Tod - und ein Nichts, das selbst den Tod noch in Frage stellt. „Ermordet wegen eines Transparentes" schreit Guy nach Billys Tod hilflos in Nacht, „und Sukarno hat es nicht einmal gesehen." Guy hat es gesehen; Billys Tod öffnet ihm ein wenig die Augen, aber verstehen tut er immer noch nicht. Am nächsten Morgen, inzwischen hat die Armee gegen Sukarno geputscht, kämpft er noch einmal um eine, um seine Story. Er versucht zum Präsidentenpalast vorzudringen, der vom Militär abgeriegelt ist. Er vertraut noch einmal auf das Privileg der Presse, seinen Status als weißer Mann und läßt den wild gestikulierenden Offizier, dessen Augen eine Sonnenbrille verbirgt, einfach schimpfend stehen. Schließlich läuft dieser Guy nach und versetzt ihm mit dem Gewehrkolben einen Schlag ins Gesicht. Mit blutendem Auge zieht sich Guy mit seinem Fahrer zurück. Sie flüchten in Billys Wohnung, Guy liegt auf dessen Pritsche, ein Arzt rät ihm zu absoluter Ruhe, wenn er sein Augenlicht retten will. Kumar, sein kommunistischer Sekretär, taucht auf und erzählt ihm, daß er des Todes ist. „Wir haben verloren", sagt er... — und dann, etwas später: „Mr. Billy Kwan hatte recht: Ihr Fremden habt keine Antworten mehr!" Des Schadenspiels letzter Akt. Da kommt Guy, im Reich des Finsternis seiner verbundenen Augen, doch noch die Erleuchtung. Er erinnert sich des Flugs, mit dem Jill Indonesien verlassen will - der Maschine, auf der er Jill prophezeit hatte, auch zu sein. „Wieviel Uhr ist es?", fragt er Kumar. — „Ein Uhr" — „Um zwei geht die Maschine, fahren wir!" Es ist noch einmal eine Fahrt auf Leben und Tod, vorbei an Massenexekutionen, im Angesicht von schwerbewaffneten Militärs, deren Blicke unerträglich lang unergründlich bleiben. Bis endlich das Wort "Jalan" fällt — „Fahrt!" Dann die Hektik des völlig überfüllten Flughafens, wo jeder alles versucht, um noch auf die Ein nervös beschleunigtes Gehen, mit der Kraft einer Verzweiflung, die die Todesgefahr im Angesicht der Erlösung nicht mehr wahrzunehmen gewillt ist — ein Einäugiger auf dem letzten Abschnitt seiner Passion, aber zumindest ein tragischer König des Herzens. Eine weiße Treppe, die von weiß gekleidetem Bodenpersonal wieder zu dem weißen Flugzeug zurückgeschoben wird, in dessen Tür Jill in einem weißen Kleid wartet und winkt. Die Farbe der westlichen Unschuld verschmilzt mit der der östlichen Trauer. Eine pathetische Szene, ohne jedes Pathos — die Magie von Peter Weir. Harald Pauli, Steadycam Nr. 36 (Winter 1998), S. 72-76 |

|||||

DVD

DVD Picture 3.5: The picture quality in the component anamorphic mode exhibits extremely good resolution with excellent detail and general sharpness throughout. Color fidelity seems slightly plugged up and unnatural in interiors, exhibiting muddy shadow detail and undefined blacks. Exterior scenes are much more natural, with vibrant color fidelity and natural fleshstones. Slight noise and minor artifacts are apparent throughout. The letterbox and anamorphic aspect ratios are measured at 2.35:1. DVD Soundtrack 2: The soundtrack is undistinguished and poorly produced monaural, despite the miscredited 2.0 Dolby Digital on the DVD jacket. This transfer is ok, considering the age of the movie, but it has some flaws. The print used for this transfer had quite a number of black and white spots. Sometimes the picture is a bit soft and occasionaly some minor compression artifacts like vanishing details and digital noise appear. Dark scenes have very little details, probably this transfer was made from a cinema print instead of a low contrast print optimized for video. The sound is mono, altough the cover states that it should be in stereo. It is not very impressive and the frequency range is somewhat limited. Peter W. Simeon, International Movie Database |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)

world, that he does not belong to the Northern Hemisphere. Looking at a photograph of Hamilton, Kwan notices a feature they share: "We are divided men.Your father American, mine Chinese. We are not really certain we are Australian, you and I. We are not quite at home in the world." Neighboring Southeast Asia offers more to the "rejects" of Europe. To come to terms with real, not imaginary geography means to overcome the sense of postcolonial isolation. On the psychological level, Hamilton's and other journalists' journey into the "otherland" may be interpreted as a search for the missing part of the self.

world, that he does not belong to the Northern Hemisphere. Looking at a photograph of Hamilton, Kwan notices a feature they share: "We are divided men.Your father American, mine Chinese. We are not really certain we are Australian, you and I. We are not quite at home in the world." Neighboring Southeast Asia offers more to the "rejects" of Europe. To come to terms with real, not imaginary geography means to overcome the sense of postcolonial isolation. On the psychological level, Hamilton's and other journalists' journey into the "otherland" may be interpreted as a search for the missing part of the self.

Peter Weir ist ein Meister der Melodrams, fast alle seine Filme sind Melos. The Year of Living Dangerously ist sein größtes. Daß sie kaum als solche wirken, liegt einerseits daran, daß Weir das gefühlsintensive und tränenreiche Potential nie ausbeutet und Schlüsselszenen eher poetisch denn pathetisch inszeniert. Und zum anderen — und das ist wohl der wichtigere Punkt- daran, daß in seinen Dreiecksgeschichten die Person, die sowohl Melo wie Drama auslöst, meist eine Metapher ist. Eine Figur, die — wenn sie denn als Charakter aus Fleisch und Blut etabliert wird — für eine fremde Welt steht. Für etwas Mysteriöses, Mythisches, Magisches — unbegreiflich eben.

Peter Weir ist ein Meister der Melodrams, fast alle seine Filme sind Melos. The Year of Living Dangerously ist sein größtes. Daß sie kaum als solche wirken, liegt einerseits daran, daß Weir das gefühlsintensive und tränenreiche Potential nie ausbeutet und Schlüsselszenen eher poetisch denn pathetisch inszeniert. Und zum anderen — und das ist wohl der wichtigere Punkt- daran, daß in seinen Dreiecksgeschichten die Person, die sowohl Melo wie Drama auslöst, meist eine Metapher ist. Eine Figur, die — wenn sie denn als Charakter aus Fleisch und Blut etabliert wird — für eine fremde Welt steht. Für etwas Mysteriöses, Mythisches, Magisches — unbegreiflich eben. landet auf der Suche nach dem Hafen, in dem die Waffen für die Kommunisten landen, in einem Hotel in den Bergen. Ein Shangrila, hoch über der Spiegel-Arena riesiger Reisterrassen (das „Weltwunder" von Banaue, der ganze Außendreh fand auf den Philippinen statt). Dort treffen Guy und sein Sekretär Kumar auf dessen geheimnisvolle Frau, die beide für die Kommunisten arbeiten. Guy erfährt, daß er auf deren Todesliste steht, und die ganze grandiose, verkommene Szenerie schaut schwer nach einem Set-up aus. Guy liegt mit einem Drink neben dem verdreckten Pool, während Kumars Frau den Laubteppich aus einer Ecke des Bassins wegschiebt und ins Wasser springt. Schweißgebadet träumt Guy danach davon, daß ihn die Frau, nach der er taucht, unter Wasser hält, bis ihm die Luft ausgegangen ist. Ein Alptraum, den Guy aber nicht zu deuten weiß. Billy besucht unterdessen eine junge Mutter in den Slums von Jakarta, deren kleiner Sohn vom verdreckten Kanalwasser krank wurde und die er finanziell unterstützt. Er kommt zu spät, der Junge ist gestorben. Der Leichnam liegt nackt aufgebahrt und wird gerade gewaschen. Zu der wimmernden Totenklage taucht die Hand des Priester in eine Wasser-Schale mit Lotus-Blättern und träufelt Tropfen auf den leblosen Körper.

landet auf der Suche nach dem Hafen, in dem die Waffen für die Kommunisten landen, in einem Hotel in den Bergen. Ein Shangrila, hoch über der Spiegel-Arena riesiger Reisterrassen (das „Weltwunder" von Banaue, der ganze Außendreh fand auf den Philippinen statt). Dort treffen Guy und sein Sekretär Kumar auf dessen geheimnisvolle Frau, die beide für die Kommunisten arbeiten. Guy erfährt, daß er auf deren Todesliste steht, und die ganze grandiose, verkommene Szenerie schaut schwer nach einem Set-up aus. Guy liegt mit einem Drink neben dem verdreckten Pool, während Kumars Frau den Laubteppich aus einer Ecke des Bassins wegschiebt und ins Wasser springt. Schweißgebadet träumt Guy danach davon, daß ihn die Frau, nach der er taucht, unter Wasser hält, bis ihm die Luft ausgegangen ist. Ein Alptraum, den Guy aber nicht zu deuten weiß. Billy besucht unterdessen eine junge Mutter in den Slums von Jakarta, deren kleiner Sohn vom verdreckten Kanalwasser krank wurde und die er finanziell unterstützt. Er kommt zu spät, der Junge ist gestorben. Der Leichnam liegt nackt aufgebahrt und wird gerade gewaschen. Zu der wimmernden Totenklage taucht die Hand des Priester in eine Wasser-Schale mit Lotus-Blättern und träufelt Tropfen auf den leblosen Körper. Maschine zu kommen. Ein letzter Opfergang, die Zollbeamten hinter sich lassend, die sich in den Schnüreln seines Tonbands verfangen, das verhallende Echo seines alten Egos im Ohr, „hier spricht Guy Hamilton...", hinaus auf Rollfeld, wo bereits die Einstiegtreppe weggerollt wird.

Maschine zu kommen. Ein letzter Opfergang, die Zollbeamten hinter sich lassend, die sich in den Schnüreln seines Tonbands verfangen, das verhallende Echo seines alten Egos im Ohr, „hier spricht Guy Hamilton...", hinaus auf Rollfeld, wo bereits die Einstiegtreppe weggerollt wird.